Hearing the Cry of the Orangutans: Unilever and Sustainable Palm Oil

As the top purchaser of palm oil globally, Unilever faces increasing cries for it to make its palm oil supply chain sustainable.

It is not often that men and women dress up as orangutans in central London. As a result, the bright orange fur was hard to miss for pedestrians walking by Unilever’s UK headquarters in April 2008.

Source: The Guardian

Protesting in conjunction with a scathing report released on Unilever’s suppliers of palm oil in Indonesia, Greenpeace activists hoped the stunt would bring attention to the catastrophic deforestation occurring as a result of the giant CPG company’s suppliers’ practices[1]. Despite its support of the top licensing body for sustainable palm oil (the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO), Unilever was facing increasing activist demands to expand its role.

Ubiquitous. Global. Everywhere.

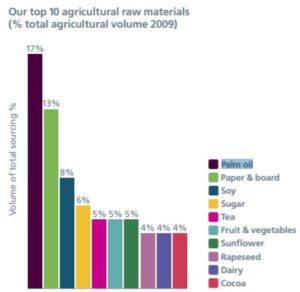

There are few companies that are ubiquitous and truly global. Unilever is one of them. Every day, over 2 billion customers use a Unilever product, many of which are made with palm oil. From shampoos to Vaseline, the company sells over 400 brands across 190 countries[2]. As a result of this scale, the company purchases over 3% of the global supply of palm oil annually.

Source: Unilever Company Website

Source: Unilever Company Website

The Dangers of Palm Oil Farming – Slash, Burn and Deforestation

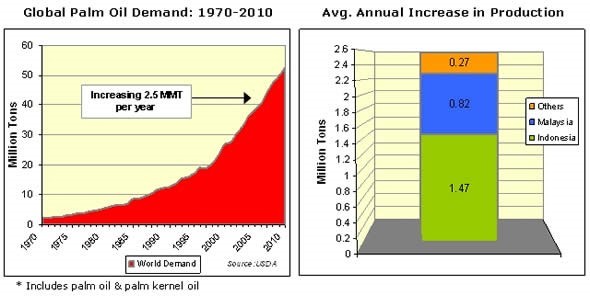

Native to west and southwest Africa, the oil palm was highly cultivated across tropic regions by the 1990s. Responding to rising demand, farmers in Indonesia and Malaysia began expanding cultivation, often by cutting down tropical forests to make room for new oil palm plantations. By 2010, demand had grown over 5x since 1990, up from 10 million tons to 50 million tons in just two decades[3].

Source: US Department of Agricutlure

The slash and burn techniques used resulted in massive CO2 emissions which drove Indonesia to 3rd in global rankings of emissions, ranking behind only the US and China. Globally, deforestation accounts for the largest share of greenhouse gas emissions of any category (15%), even more than entire industries like transportation[4].

As activists pushed awareness of the increasing climate costs of palm oil production, it became important for brands like Unilever to develop oil palm standards that would reduce deforestation.

Unilever Responds

Facing this mounting pressure, Unilever responded to environmental concerns with its Sustainable Living Plan in 2010. Included in its goals, Unilever promised to, “purchase all palm oil from sustainable sources by 2015.”[5] Unfortunately, by 2015 it had only achieved sustainable sourcing for 19% of its palm oil. In an update, the company reset goals to achieve 100% by 2019[6]. Additionally, the company released new guidelines for sustainable palm oil[7].

Within these reports, Unilever called out the challenge of traceability of palm oil through its supply chain. This problem arose from the fact that Unilever did not own or operate its palm oil suppliers, but relied on purchasing mostly non-segregated mixes of sustainable and unsustainable palm oils.

As a result of limited traceability, Unilever opted to offset the majority of its palm oil purchases with “GreenPalm Certificates”. Sold by the RSPO, these functioned similarly to carbon credits, and were sold by RSPO certified sustainable producers. As of Unilever’s latest report, only 10% of its palm oil was traceable while the remaining 90% was offset by GreenPalm certificates.[8] That said, the company vowed to increase traceability to 100% by 2017.

Oil palm plants & farmers. Source: Foodnavigator-usa.com.

GreenPalm Certificates – Not far Enough?

While several activist groups applauded Unilever’s approach, others felt the GreenPalm certificates were an easy way out of a more entrenched problem. These activists disliked that the company had done little to actually change the behaviors and processes of existing suppliers. The Rainforest Alliance Network released a scathing report in 2015 in which it wrote, “Unilever’s reliance on GreenPalm certificates remains a critical shortfall in its approach, as this offset model does not directly improve the practices of the companies from which it sources palm oil.”[9] In the report the group noted that while Unilever had been one of the first to start the conversation, it was now lagging behind companies pushing suppliers toward sustainability practices.

Source: www.plantationsinternational.com

Going Forward – Listening to the Orangutans

In recent years, activists have gained heightened influence over consumer perception, forcing brands to stay a step ahead of negative publicity. Given its scale, Unilever must listen to the early criticisms of its palm oil plan and move beyond GreenPalm certificates. This does not require vertical integration. Rather, Unilever should take steps to train suppliers in its supply chain. Additionally, it should cut the most egregious offenders entirely. While certificates functioned as an interim solution to mitigate lack of traceability, as this data becomes available, the time is clearly coming to move beyond offsets.

If the company does not, then look for more orangutan costumed activists at Unilever headquarters in the near future.

(789 words).

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2008/apr/21/wildlife

[2] https://www.unilever.com/about/who-we-are/

[3] http://www.pecad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2010/10/Indonesia/

[4] http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/deforestation/

[5] https://www.unilever.com/Images/unileversustainablelivingplan_tcm13-387356_tcm244-409855_en.pdf

[6] https://www.unilever.com/sustainable-living/the-sustainable-living-plan/reducing-environmental-impact/sustainable-sourcing/transforming-the-palm-oil-industry/

[7] https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-palm-oil-policy-2016_tcm244-479933_en.pdf

[8] https://www.unilever.com/Images/uslp-unilever-palm-oil-report-nov14_tcm244-424235_en.pdf

[9] https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/rainforestactionnetwork/pages/5884/attachments/original/1435772500/RAN_TESTING_COMMITMENTS_2015_FINAL.pdf?1435772500

It’s interesting to think that Unilever, a company with such scale and influence, has made such little effort to meet its own internal goals around palm oil. When announcing these types of initiatives, most corporations understand the negative PR that comes from not meeting them, or at least getting very close. Unilever fell short by 90%, and then decided to try to make up for it with the purchase of certificates. Like the author puts forth, this seems lazy. If Unilever was very serious about the issue, they would look to vertically integrate and buy plants themselves. However, it is clear that this is not cost effective and that they will continue to purchase from companies who don’t see climate change as a priority. I agree that the first step would be to seriously threaten to, or actually cut ties with suppliers that don’t meet the appropriate standards. Unilever can use its size as leverage.

I am struck by the similarities between this post and the IKEA case we discussed in TOM class on Friday. Interestingly, IKEA chose to vertically integrate its lumber supplies, and while IKEA also faced challenges, my sense is that IKEA is further along than Unilever in meeting its own sustainability goals. As we discussed in class, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, but I would be very interested to see a general study of many companies facing this dilemma (vertical integration versus getting tough on independent suppliers).

One other question I have is what happens to the proceeds from the GreenPalm certificates? I understand that environmental groups have concerns about the efficacy of these certificates, but perhaps if the proceeds are spent wisely (i.e., invested in longer-term sustainable solutions or alternatives), it could help to mitigate concerns.

There is a whole world of opportunities around palm-oil sustainability: Palm oil is in many places a resource of production for small families, and as such, there is a lot of space to share best practices and introduce mechanization to increase productivity. It would be interesting for companies like Unilever to engage in this aspect with its supply chain, either directly or through cooperatives, that in many places, oversee the production of small farmers. The increase of productivity could also prove beneficial to deter deforestation practices, specially in places like South East Asia where the extension of land dedicated to Palm oil has surpassed the limit of sustainability. Still, the timing that both regulation organisms and companies are taking to effectively comply with sustainable sourcing of Palm Oil (certified) can do nothing but pose doubts on whether any additional effort of increasing palm oil productivity could be achieved in the short term.

This sounds remarkably similar to the IKEA case and I think that there are similar lessons. First, it is clear that these companies generate negative externalities that aren’t captured in their P&L and it is important that activists are forcing the public to see that this is the case in order to change the behavior and decision making at these companies. The second is that the public, shareholders and media should be very leery that any elegant solution like GreenPalm certificates somehow solve things. It is very clear that this is the easy path forward for the company to save face without actually solving anything. If Unilever could actually farm sustainably for the same price then they clearly would have done that over some roundabout method. The final lesson is that if a company wants something done right, then they have to do it themselves. In this case it requires Unilever to vertically integrate and buy palm oil farms to ensure compliance and sustainability. In the short term this will be unprofitable and unacceptable to many shareholders, but it will create a first mover advantage with activists and therefore consumers in the long run.

I applaud Unilever for trying to increase the sustainability of their palm oil supplies, but what it fails to acknowledge is whether there truly is a sustainable source of palm oil, or if that goal is simply a figment of some supply chain imagination. Unlike carbon emissions, which truly are transferable and indistinguishable, these sorts of habitat banks and credits often lead to lower quality habitat being preserved as equal, which in the case of Indonesian rainforest could leave the protected land effectively useless for either humans or animals. What is most concerning, though, is that there is no mention to actually move the recipes away from palm oil towards more sustainable inputs. Instead of trying to make marginal improvements, why don’t they push for a wholesale transition?

Erik, thank you for writing this. I have spent some time working for an agricultural commodity company that has palm and soybean on its portfolio. The company manages palm oil plantations, processes the oil into food/biodiesel/chemicals and trades it globally. Certification and trace-ability is a big part of the conversation now. Palm is chemically versatile and more economical than many other oilseeds such as coconut/rapeseed which is why it has found uses in almost all products from cookies to laundry detergent. Having said that, I admit there are many opportunities for the certification standards to improve. For example RSPO uses some of the same criteria that FSC uses – HCV forest, which experts agree should not be cleared. HCV is in itself debatable because it is not a scientific metric that can be measured and is not the same as “primary or secondary forest”. There are also many advocacy groups pushing for other standards of certification which makes vetting the supply chain all the more tedious. Given the situation in 2015, the previous company I worked for has put a moratorium on further land development. In addition, many existing plantations have adopted a “forest buffer zone” so endemic wildlife have a chance to survive. Many initiatives such as these are work in progress so I hope to keep you posted!

I want to echo Drew’s comment above. After reading this post, the first thought that came to mind was is there a viable substitute? If harvesting palm oil is so deleterious to the environment and Unilever’s sustainability efforts have failed to meet their set goals, could Unilever reconsider its use of palm oil altogether?

I did a bit of googling and found this article, which discusses this exact issue (see link below). It sounds like palm oil has “two main stellar properties: an exceptionally high melting point and very high saturation levels” — a characteristic not shared by any other vegetable oil. However, research suggests that yeast, which would require 10-100 times less land for production, may be a viable alternative. I hope this is something Unilever is looking into!

https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/feb/17/scientists-reveal-revolutionary-palm-oil-alternative-yeast

Coming from Indonesia, I am deeply skeptical if ever Unilever can source sustainable palm oil. First of all, sustainable palm oil is a paradoxical notion. While the burning of palm oil is carbon neutral, the production process involves so much environmental destruction that it’s hard to find producers who do it in a sustainable manner. Oftentimes companies exclude certain environmental impact from their accounting, pushing away costs from their books, as opposed to truly reflecting the environmental costs of palm oil production in its entirety. Second, majority of the world’s palm oil supply come from Malaysia and Indonesia, and there’s very little incentive for businesses in Indonesia to make sustainable palm oil. The Indonesian government needs the money more than it needs forests so it turns a blind eye on the issue and deems palm oil as environmentally good and provides minimal oversight. Pressure to change must come from demand side (i.e. Unilever) or public organizations.

Very interesting read. This article makes me wonder whether Unilever should shift the conversation from sourcing sustainable palm oil to replacing palm oil with an alternative that is more fundamentally sustainable. It is clear that Unilever is having a difficult time in tracing the origin of all its palm oil, and I don’t think that they will ever be fully confident that its sourced sustainable given the scale of their operation and the decentralized nature of the palm oil industry. As long as there is strong global palm oil demand, there will be farmers in developing countries incentivized to slash and burn indigenous forest to grow palm oil satiate that demand so that they can better provide for their families.

Wonder how substitutable palm oil is and whether Unilever’s R&D efforts could be directed to that effect. GreenPalm certificates seemed destined to go the way of European carbon emissions trading certificates only with even smaller chance of success given the less developed national regulatory structures…

Erik,

Thank you very much for this informative article. I knew little about palm oil prior to reading this but based on my personal experience trying to buy palm oil once I am very surprised that Unilever is as large of a consumer of palm oil as it is without being a more critical purchaser. Last year I tried to buy palm oil at a Safeway grocery store for a new recipe I was trying. When I wasn’t able to find it in the store, I googled the product and found out that many grocery stores such as Safeway are forcing their suppliers to switch over to 100% sustainably sourced palm oil because of these exact environmental issues you outlined. http://www.prevention.com/food/smart-shopping/supermarkets-ban-palm-oil . It is clear though that many of the largest corporate purchasers of palm oil can be doing more. Thanks.