This post was originally published by Carmen Nobel for HBS Working Knowledge.

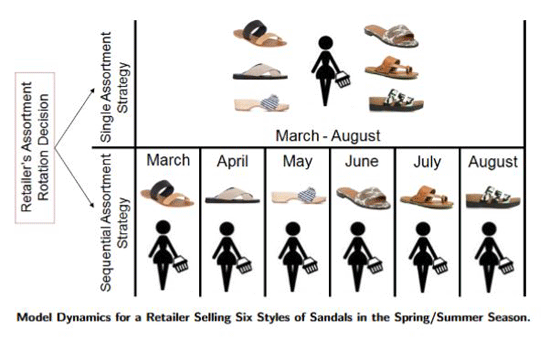

Retailers routinely swap out the products they display to customers. It’s called assortment rotation, and it’s a popular business strategy for many brick-and-mortar and online stores alike. Retailing trends such as “fast fashion” (think Zara and H&M) and “flash sales” (think Rue La La) depend on rapid rotations.

New research considers the wisdom of frequent assortment rotation in cases in which a retailer has many new varieties of a product to sell—nine different silver necklaces, say, or 17 different toaster ovens. Is it smart to show a few products at a time, thus always concealing a portion of your full product catalog—and leaving customers to wonder what you’ll offer next? Or is it better to display all your wares at once, in hopes of encouraging a shopping spree? For example, is a customer more likely to buy three of those silver necklaces if she sees all nine displayed at once, or if she sees them a few at a time throughout the season?

“IN PRODUCT CATEGORIES WHERE THE CONSUMER IS LIKELY TO PURCHASE SEVERAL PRODUCTS, THE VALUE OF CONCEALMENT TENDS TO BE POSITIVE”

The answer depends on the product category, according to the paper Assortment Rotation and the Value of Concealment, co-authored by Kris Johnson Ferreira and Joel Goh, both assistant professors in the Technology and Operations Management Unit at Harvard Business School.

The paper is novel in that it considers product categories in which consumers are likely to buy more than one product in a selling season. Most of the previous research on assortment rotation has focused on retail categories in which consumers would rarely buy more than one type of item unless the previous one needed to be replaced—like automobiles, toasters, or engagement rings.

Source: Assortment Rotation and the Value of Concealment copyright 2016 by Kris Johnson Ferreira and Joel Goh

Ferreira and Goh launched the research after a conversation with an executive at flash sales boutique Rue La La, with whom Ferreira had conducted previous research on product pricing. “He wondered what new products they should be offering,” Ferreira recalls. “And how should they think about things like the length of a sales event?”

“What we found was that in product categories where the consumer is likely to purchase several products, the value of concealment tends to be positive,” she explains. “However, for product categories where the consumer is likely to purchase one product at most, the value of concealment is typically negative, so it’s better to show them all at the same time.”

In other words, if you’re looking to sell products like shoes or sweatshirts, it’s better to tantalize consumers by offering only a few products at a time, concealing the others until a later date. If a customer buys one pair of black boots online in August, but then the retailer reveals an even better pair in September, she’s likely to buy the second one, too. But if she sees a season’s worth of boots displayed at the same time, along with a bunch of other boots, then she’s likely to just buy the one pair she likes best. “That’s the value of concealment,” Ferreira says.

However, if you’re trying to sell engagement rings or kitchen appliances, it’s better to display them all at once. In cases like that, “concealing products for later in the selling season may cause the customer to pass on buying a product that she really liked, only to find out that she doesn’t like any of the subsequent products either,” Ferreira says.

Beyond flash sales and fast fashion, the research has practical implications for any retailer wrestling with the best way to handle assortment rotation strategy—even restaurants.

“For example, some sushi restaurants serve unique sushi rolls on a conveyor belt that passes in front of customers,” Ferreira and Goh write in the paper. “Customers must decide whether or not they want to purchase the sushi roll before observing subsequent sushi rolls that will be added to the conveyor belt later in the meal. Since customers are likely to purchase many sushi rolls over the course of a dinner, our results suggest that [all else being equal] customers may end up purchasing more sushi at such a restaurant compared to a sushi restaurant where customers order from a fixed menu.”

Next steps

The mathematical model in the paper assumes a situation in which a retailer would sell all styles of a product at the same price (e.g., all fall sandals would be priced at $60 a pair). In the next stage of their research, Ferreira and Goh would like to determine the best way to sell similar products with varying levels of pricing, quality, or attractiveness. Once a retailer has decided to employ an assortment rotation strategy, what is the best order to display the products?

“Consider a situation in which you have different prices across a product line of black boots,” Ferreira says. “Should you offer the most expensive boot first and [successively] offer cheaper boots, or display them in some other order? Or, if a retailer believes customers may like one new boot more than another, should the retailer show the most attractive one first or second?”

Note to readers: As they continue their research, Ferreira and Goh would like to team up with retailers to test their models in real-world settings. If you think your company might benefit from empirical testing of various assortment rotation strategies, please send an email to Kris Ferreira at kferreira@hbs.edu.