This post was originally published by Trushar Barot for Harvard’s Nieman Lab.

This year, the iPhone turned 10. Its launch heralded a new era in audience behavior that fundamentally changed how news organizations would think about how their work is discovered, distributed and consumed.

This summer, as a Knight Visiting Nieman Fellow at Harvard, I’ve been looking at another technology I think could lead to a similar step change in how publishers relate to their audiences: AI-driven voice interfaces, such as Amazon’s Alexa, Google’s Home and Assistant, Microsoft’s Cortana, and Apple’s upcoming HomePod. The more I’ve spoken to the editorial and technical leads building on these platforms in different news organizations, as well as the tech companies developing them, the more I’ve come to this view: This is potentially bigger than the impact of the iPhone. In fact, I’d describe these smart speakers and the associated AI and machine learning that they’ll interface with as the huge burning platform the news industry doesn’t even know it’s standing on.

This wasn’t how I planned to open this piece even a week before my Nieman fellowship ended. But as I tied together the research I’d done with the conversations I’d had with people across the industry, something became clear: As an industry, we’re far behind the thinking of the technology companies investing heavily in AI and machine learning. Over the past year, the CEOs of Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and other global tech giants have all said, in different ways, that they now run “AI-first” companies. I can’t remember a single senior news exec ever mentioning AI and machine learning at any industry keynote address over the same period.

Of course, that’s not necessarily surprising. “We’re not technology companies” is a refrain I’ve heard a lot. And there are plenty of other important issues to occupy industry minds: the rise of fake news, continued uncertainty in digital advertising, new tech such as VR and AR, and the ongoing conundrum of responding to the latest strategic moves of Facebook.

But as a result of all these issues, AI is largely being missed as an industry priority; to switch analogies, it feels like we’re the frog being slowly boiled alive, not perceiving the danger to itself until it’s too late to jump out.

“In all the speeches and presentations I’ve made, I’ve been shouting about voice AI until I’m blue in the face. I don’t know to what extent any of the leaders in the news industry are listening,” futurist and author Amy Webb told me. As she put it in a piece she wrote for Nieman Reports recently:

Talking to machines, rather than typing on them, isn’t some temporary gimmick. Humans talking to machines — and eventually, machines talking to each other — represents the next major shift in our news information ecosystem. Voice is the next big threat for journalism.

My original goal for this piece was to share what I’d learned — examples of what different newsrooms are trying with smart speakers and where the challenges and opportunities lie. There’s more on all that below. But I first want to emphasize the critical and urgent nature of what the news industry is about to be confronted with, and how — if it’s not careful — it’ll miss the boat just as it did when the Internet first spread from its academic cocoon to the rest of the world. Later, I’ll share how I think the news industry can respond.

Talking to objects isn’t weird any more

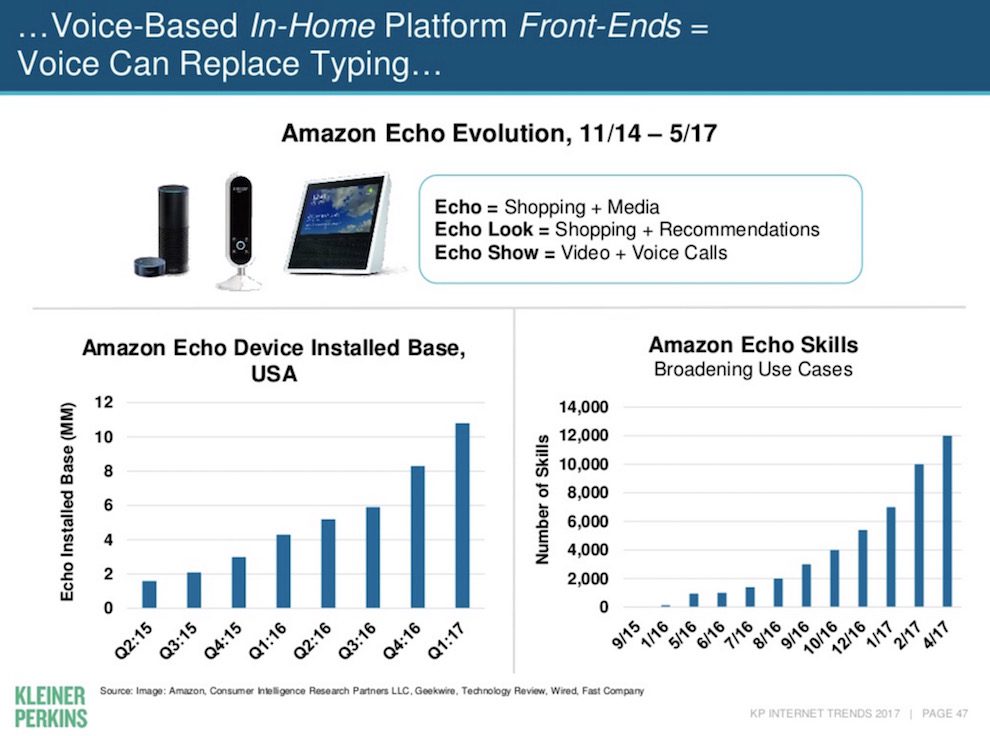

In the latest version of her annual digital trends report, Kleiner Perkins’ Mary Meeker revealed that 20 percent of all Google search was now happening through voice rather than typing. Sales of smart speakers like Amazon’s Echo were also increasing fast:

It’s becoming clear that users are finding it useful to interact with devices through voice. “We’re treating voice as the third wave of technology, following the point-and-click of PCs and touch interface of smartphones,” Francesco Marconi, a media strategist at Associated Press, told me. He recently coauthored AP’s report on how artificial intelligence will impact journalism. The report gives some excellent insights into the broader AI landscape, including automation of content creation, data journalism through machine learning, robotic cameras, and media monitoring systems. It highlighted smart speakers as a key gateway into the world of AI.

Since the release of the Echo, a number of outlets have tried to learn what content works (or doesn’t) on this class of devices. Radio broadcasters have been at an understandable advantage, being able to adapt their content relatively seamlessly.

In the U.S., NPR was among the first launch partners on these platforms. Ha-Hoa Hamano, a senior product manager at NPR working on voice AI, described its hourly newscast as “the gateway to NPR’s content.”

“We’re very bullish on the opportunity with voice,” Hamano said. She cited research showing 32 percent of people aged 18 to 34 don’t own a radio in their home — “which is a terrifying stat when you’re trying reach and grow audience. These technologies allow NPR to fit into their daily routine at home — or wherever they choose to listen.”

NPR was available at launch on the Echo and Google Home, and will be soon on Apple’s HomePod. “We think of the newscast as the gateway to the rest of NPR’s news and storytelling,” she said. “It’s a low lift for us to get the content we already produce onto these platforms. The challenge is finding the right content for this new way of listening.”

The API that drives NPR made it easy for Hamano’s team to integrate the network’s content into Amazon’s system. NPR’s skills — the voice-driven apps that Amazon’s voice assistant Alexa recognizes — can respond to requests like “Alexa, ask NPR One to recommend a podcast” or “Alexa, ask NPR One to play Hidden Brain.”

Voice AI: What’s happening now

- Flash briefings (e.g., NPR, BBC, CNN)

- Podcast streaming (e.g., NPR)

- News quizzes (e.g., The Washington Post)

- Recipes and cooking aide (e.g., Hearst)

The Washington Post — owned by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos — is also an early adopter in running a number of experiments on Amazon’s and Google’s smart speaker platforms. Senior product manager Joseph Price has been leading this work. “I think we’re at the early stages of what I’d call ambient computing — technology that reduces the ‘friction’ between what we want and actually getting it in terms of our digital activity,” he said. “It will actually mean we’ll spend less time being distracted by technology, as it effectively recedes into the background as soon as we are finished with it. That’s the starting point for us when we think about what voice experiences will work for users in this space.”

Not being a radio broadcaster, the Post has had to experiment with different forms of audio — from using Amazon’s Alexa automated voices on stories from its website to a Post reporter sharing a particular story in their own voice. Other experiments have included launching an Olympics skill, where users could ask the Post who had won medals during last year’s Olympics. That was an example of something that didn’t work, though — Amazon built the same capability into the main Alexa platform soon afterwards itself.

“That was a really useful lesson for us,” Price said. “We realized that in big public events like these, where there’s an open data set about who has won what, it made much more sense for a user to just ask Alexa who had won the most medals, rather than specifically asking The Washington Post on Alexa the same question.” That’s a broader lesson: “We have to think about what unique or exclusive information, content, or voice experience can The Washington Post specifically offer that the main Alexa interface can’t.”

One area that Price’s team is currently working on is the upcoming release of notifications on both Amazon’s Alexa and Google’s Home platforms. For instance, if there’s breaking news, the Post will be able to make a user’s Echo chime and flash green, at which point the user can ask “Alexa, what did I miss?” or “Alexa, what are my notifications?” Users will have to opt in before getting alerts to their device, and they’ll be able to disable alerts temporarily through a do-not-disturb mode.

Publishers like the Post that produce little or no native audio content have to work out the right way of presenting their text-based content on a voice-driven platform. One option is to allow Alexa to read stories that have been published; that’s easy to scale up. The other is getting journalists to voice articles or columns or create native audio for the platform. That’s much more difficult to scale, but several news organizations told me initial audience feedback suggests this is users’ preferred experience.

For TV broadcasters like CNN, early experiments have focused on trying to figure out when their users would most want to listen to a bulletin — as opposed to watching one — and how much time they might have specifically to do so via a smart speaker. Elizabeth Johnson, a senior editor at CNN Digital, has been leading the work on developing flash-briefing content for these platforms.

“We assumed some users would have their device in the kitchen,” she said. “This led us to ask, what are users probably doing in the kitchen in the morning? Making breakfast. How long does it take to make a bagel? Five minutes. So that’s probably the amount of time a user has to listen to us, so let’s make sure we can update them in less than five minutes. For other times of the day, we tried to understand what users might be doing: Are they doing the dishes? Are they watching a commercial break on TV or brushing their teeth? We know that we’re competing against a multitude of options, so what sets us apart?”

With Amazon’s recent release of the Echo Show — which has a built-in screen — CNN is taking the “bagel time” philosophy to developing a dedicated video news briefing at the same length as its audio equivalent.

CNN is also thinking hard about when notifications will and won’t work. “If you send a notification at noon, but the user doesn’t get home until 6 p.m., does it make sense for them to see that notification?” Johnson asked. “What do we want our users to hear when they come home? What content do we have that makes sense in that space, at that time? We already consider the CNN mobile app and Apple News alerts to be different, as are banners on CNN.com — they each serve different purposes. Now, we have to figure out how to best serve the audience alerts on these voice-activated platforms.”

What’s surprised many news organizations is how broad the age range of their audiences are on smart speakers. Early adopters in this space are very different from early adopters of other technologies. Many didn’t buy these smart speakers themselves, but were given them as gifts, particularly around Christmas. The fact there’s very little learning curve to use them means the technical bar is much lower. Speaking to the device is intuitive.

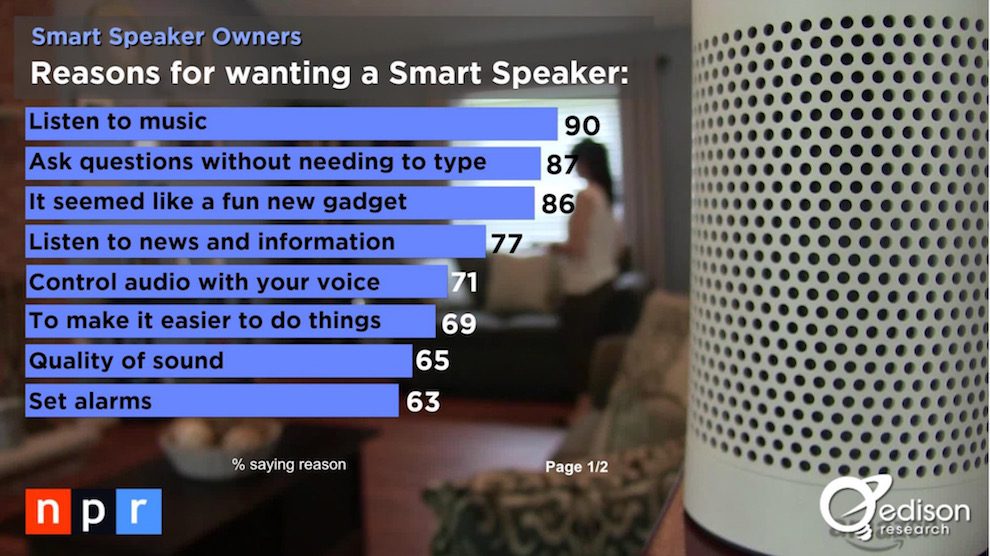

Edison Research was recently commissioned by NPR to find out more about what these users are doing with these devices. Music was unsurprisingly at the top of the reasons why they use these devices, but coming in second was to “ask questions without needing to type.” Also high up was an interest to listen to news and information — encouraging for news organizations.

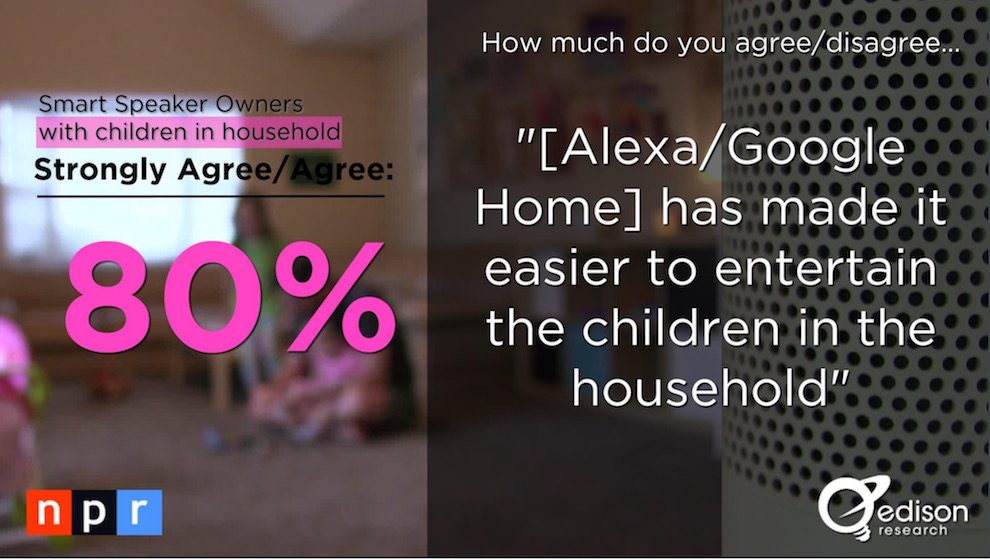

While screens aren’t going away — people will always want to see and touch things — there’s no doubt that voice as an interface for devices is already becoming ingrained as a natural behavior among our audiences. If you’re not convinced, watch children interact with smart speakers: Just as we’ve seen the first Internet-connected generation grow up, we’re about to see the “voice generation” arrive feeling completely at ease with this way of engaging with technology.

The NPR–Edison research has also highlighted this trend. Households with kids that have smart speakers say engagement is high with these devices. Unlike phones or tablet, smart speakers are communal experiences — which also raises the likelihood of families spending time together, whether for education or entertainment purposes.

(It’s worth noting here that there have been some concerns raised about whether children asking for — or demanding — content from a device without saying “please” or “thank you” could have downsides. As San Francisco VC and dad Hunter Walk put it last year: “Amazon Echo is magical. It’s also turning my kid into an asshole.” To curb this, skills or apps for children could be designed in the future with voice responses requiring politeness.)

For the BBC, where I work, developing a voice-led digital product for children is an exciting possibility. It already has considerable experience of content for children on TV, radio, online and digital.

“Offering the ability to seamlessly navigate our rich content estate represents a great opportunity for us to forge a closer relationship with our audience and to serve them better,” Ben Rosenberg, senior distribution manager at the BBC, said. “The current use cases for voice suggest there is demand that sits squarely in the content areas where we consistently deliver on our ambitions — radio, news, and children’s genres.”

BBC News recently formed a working group to rapidly develop prototypes for new forms of digital audio using voice as the primary interface. Expect to hear more about this in the near future.

Rosenberg also highlights studies that have found voice AI interfaces appeared to significantly increase consumption of audio content. This is something that came out strongly in the NPR-Edison research too:

Owning a smart speaker can lead to a sizeable increase in consumption of music, news and talk content, podcasts, and audiobooks. Media organizations that have such content have a real opportunity if they can figure out how to make it as easily accessible through these devices as possible. That’s where we get to the tricky part.

Challenges: Discovery, distribution, analytics, monetization

In all the conversations I’ve had with product and editorial teams working on voice within news organizations, the biggest issue that comes up repeatedly is discovery: How do users get to find the content, either as a skill or app, that’s available to them?

With screens, those paths to discovery are relatively straightforward: app stores, social media, websites. These are tools most smartphone users have learned to navigate pretty easily. With voice, that’s more difficult: While accompanying mobile apps can help you navigate what a smart speaker can do, in most cases, that isn’t the natural way users will want to behave.

If I was to say: “Hey Alexa/Google/Siri, what’s in the news today?” — what are these voice assistants doing in the background to deliver back to me an appropriate response? Big news brands have a distinct advantage here. In the U.K., most users who want news are very likely to ask for the BBC. In the U.S., it might be CNN or NPR. It will be more challenging for news brands that don’t have a natural broadcast presence to immediately come to the mind of users when they talk to a smart speaker for the first time; how likely is it that a user wanting news would first think of a newspaper brand on these devices?

Beyond that, there’s still a lot of work to be done by the tech platforms to make discovery and navigation easier. In my conversations with them, they’ve made it clear they’re acutely aware of that and are working hard to do so. At the moment, when you set up a smart speaker, you set preferences through the accompanying mobile app, including prioritizing the sources of content you want — whether for music, news, or something else. There are plenty of skills or apps you can add on. But as John Keefe, app product manager at Quartz, put it: “How would you remember how to come back to it? There are no screens to show you how to navigate back and there are no standard voice commands that have emerged to make that process easier to remember.”

Another concern that came up frequently: the lack of industry standards for voice terms or tagging and marking up content that can be used by these smart speakers. These devices have been built with natural language processing, so they can understand normal speech patterns and derive instructional meaning for them. So “Alexa, play me some music from Adele” should be understood in the same way as “Alexa, play Adele.” But learning to use the right words can still sometimes be a puzzle. One solution is likely to be improving the introductory training that starts up when a smart speaker is first connected. It’s a very rudimentary experience so far, but over the next few months, this should improve — giving users a clearer idea of how they can know what content is available, how they can skip to the next thing, go back, or go deeper.

Voice AI: Challenges

- Discoverability

- Navigation

- Consistent taxonomies

- Data analytics/insights

- Monetization

- Having a “sound” for your news brand

Lili Cheng, corporate vice president at Microsoft Research AI, which develops its own AI interface Cortana, described the challenge to Wired recently: “Web pages, for example, all have back buttons and they do searches. Conversational apps need those same primitives. You need to be like, ‘Okay, what are the five things that I can always do predictably?’ These understood rules are just starting to be determined.”

For news organizations building native experiences for these platforms, a lot of work will need to be done in rethinking the taxonomy of content. How can you tag items of text, audio, and video to make it easy for voice assistants to understand their context and when each item would be relevant to deliver to a user?

The AP’s Marconi described what they’re already working on and where they want to get to in this space:

At the moment, the industry is tagging content with standardized subjects, people, organizations, geographic locations and dates, but this can be taken to the next level by finding relationships between each tag. For example, AP developed a robust tagging system called AP Metadata which is designed to organically evolve with a news story as it moves through related news cycles.

Take the 2016 water crisis in Flint, Michigan, for example. Until it became a national story, Flint hadn’t been associated with pollution, but as soon as this story became a recurrent topic of discussion, AP taxonomists wrote rules to be able to automatically tag and aggregate any story related to Flint or any general story about water safety moving forward. The goal here is to assist reporters to build greater context in their stories by automating the tedious process often found in searching for related stories based on a specific topic or event.

The next wave of tagging systems will include identifying what device a certain story should be consumed on, the situation, and even other attributes relating to emotion and sentiment.

As voice interfaces move beyond just smart speakers to all the devices around you, including cars and smart appliances, Marconi said the next wave of tagging could identify new entry points for content: “These devices will have the ability to detect a person’s situation and well as their state of mind at a particular time, enabling them to determine how they interact with the person at that moment. Is the person in an Uber on the way to work? Are they chilling out on the couch at home or are they with family? These are all new types of data points that we will need to start thinking about when tagging our content for distribution in new platforms.”

This is where industry-wide collaboration to develop these standards is going to be so important — these are not things that will be done effectively in the silos of individual newsrooms. Wire services like AP, who serve multiple news clients, could be in an influential position to help form these standards.

Audience data and measuring success

As with so many new platforms that news organizations try out, there’s an early common complaint: We don’t have enough data about what we’re doing and we don’t know enough about our users. From the dozen or so news organizations I’ve talked to, nearly all raised similar issues in getting enough data to understand how effective their presence on these platforms was. A lot seems to depend on the analytics platform that they use on their existing websites and how easy it is to integrate into Amazon Echo and Google Home systems. Amazon and Google provide some data and though it’s basic at this stage, it is likely to improve.

With smart speakers, there are additional considerations to be made beyond the standard industry metrics of unique users, time spent and engagement. What, for example, is a good engagement rate — the length of time someone talks to these devices? The number of times they use the particular skill/app? Another interesting possibility that could emerge in the future is being able to measure the sentiment behind the experience a user has after trying out a particular skill/app through the tone of their voice. It may be possible in future to tell whether a user sounded happy, angry or frustrated — metrics that we can’t currently measure with existing digital services.

And if these areas weren’t challenging enough, there’s then the “M” word to think about…

Money, money, money

How do you monetize on these platforms? Understandably, many news execs will be cautious in placing any big bets of new technologies unless there is a path they can see towards future audience reach or revenue (ideally both). For digital providers, there would be a natural temptation to try and figure out how these voice interfaces could help drive referrals or subscriptions. However, a more effective way of looking at this would be through the experience of radio. Internal research commissioned by some radio broadcasters that I’ve seen suggests users of smart speakers have a very high recall rate of hearing adverts while listening to radio being streamed on these devices. As many people are used to hearing ads in this way, it could mean they will have a higher tolerance level to such ads via smart speakers compared to pop-up ads on websites.

One of the first ad networks developed for voice assistants by VoiceLabs gave some early indicators to how advertising could work on these devices in the future — with interactive advertising that converses with uses. After a recent update on its terms by Amazon, VoiceLabs subsequently suspended this network. Amazon’s updated terms still allow for advertising within “flash briefings’, podcasts and streaming skills.

Another revenue possibility is if smart speakers — particularly Amazon’s at this stage — are hard wired into shopping accounts. Any action a user takes that leads to a purchase after hearing a broadcast or interacting with a voice assistant could lead to additional revenue streams.

For news organizations that don’t have much broadcast content and are more focused online, the one to watch is the Washington Post. I’d expect to see it do some beta testing of different revenue models through its close relationship with Amazon over the coming months, which could include a mix of sponsored content, in-audio ads and referral mechanisms to its website and native apps. These and other methods are likely to be offered by Amazon to partners for testing in the near future too.

Known unknowns and unknown unknowns

While some of the challenges — around discovery, tagging, monetization — are getting pretty well defined as areas to focus on, there are a number of others that could lead to fascinating new voice experiences — or could lead down blind alleys.

There are some who think that a really native interactive voice experience will require news content to replicate the dynamics of a normal human conversation. So rather than just hearing a podcast or news bulletin, a user could have a conversation with a news brand. What could that experience be? One example could be looking at how users could speak to news presenters or reporters.

Rather than just listening to a CNN broadcast, could a user have a conversation with Anderson Cooper? It wouldn’t have to be the actual Anderson Cooper, but it could be a CNN app with his voice and powered by natural language processing to give it a bit of Cooper’s personality. There could be similar experiences that could be developed for well known presenters and pundits for sports broadcasters. This would retain the clear brand association while also giving a unique experience that could only happen through these interfaces.

Another example could be entertainment shows that could bring their audience into their programmes, quite literally. Imagine a reality TV show where rather than having members of the public performing on stage, they simply connect to them through their home smart speakers via the internet and get them to do karaoke from home. With screens and cameras coming to some of these smart speakers (eg the Amazon Echo Show and Echo Look), TV shows could link up live into the homes of their viewers. Some UK TV viewers of a certain age may recognize this concept (warning, link to Noel’s House Party) .

Voice AI: Future use cases

- Audiences talking to news/media personalities

- Bringing audiences into live shows directly from their homes

- Limited lifespan apps/skills for live events (e.g. election)

- Time-specific experiences (e.g. for when you wake up)

- Room-optimized apps/skills for specific home locations

Say that out loud

Both Amazon and Google have been keen to emphasize the importance of a news brands getting their “sound” right. While it may be easy to integrate the sound identity for radio and TV broadcasters, it will be something that print and online players will have to think carefully about.

The name of the actual skill/app that a news brand creates will also need careful consideration. The Amazon skill for the news site Mic (pronounced “mike’) is named “Mic Now’, rather than just Mic — as otherwise Alexa would find difficult to distinguish from a microphone. The clear advice is: stay away from generic sounding services on these platforms, keep the sound distinct.

Apart from having these established branded news services on these platforms, we could start to see experimentation with hyper-specific of limited lifespan apps. There is increasing evidence to suggest that as these speakers appear not just in the living room (their most common location currently), but also in kitchens, bathrooms and bedrooms, apps could be developed to work primarily based on those locations.

Hearst Media has already successfully rolled out a cooking and recipe app on Alexa for one of its magazines, intended for use specifically in the kitchen to help people cook. Bedtime stories or lullaby apps could be launched to help children fall asleep in their bedrooms. Industry evidence is emerging to suggest that the smart speaker could replace the mobile phone as the first and last device we interact with each day. Taking advantage of this, could there be an app that is designed specifically to engage you in the first one or two minutes after your eyes open in the morning and before you get out of bed? Currently a common behaviour is to pick up the phone and check your messages and social media feed. Could that be replaced with you first talking to your smart speaker when waking up instead?

Giving voice to a billion people

While these future developments are certainly interesting possibilities, there is one thing I find incredibly exciting: the transformative impact voice AI technology could have in emerging markets and the developing world. Over the next three or four years, a billion people — often termed “the next billion” — will connect to the internet for the first time in their lives. But just having a phone with an internet connection itself isn’t going to be that useful — as they will have no experience of knowing how to navigate a website, use search or any of the online services we take for granted in the west. What could be genuinely transformative though is if they are greeted with a voice-led assistant speaking to them in their language and talking them through how to use their new smartphone and help them navigate the web and online services.

Many of the big tech giants know there is a big prize for them if they can help connect these next billion users. There are a number of efforts from the likes of Google and Facebook to make internet access easier and cheaper for such users in the future. However, none of the tech giants are currently focused on developing their voice technology to these parts of the world, where literacy levels are lower and oral traditions are strong — a natural environment where Voice AI technology would thrive, if the effort to develop it in non-English languages is made. Another big problem is that all the machine learning that voice AI will be built on currently is dominated by English datasets, with very little being done in other languages.

Some examples of what an impact voice assistants on phones could have to these “next billion” users in the developing world include:

Voice AI: Use cases for the “next billion”

- Talking user through how to use phone functions for the first time

- Setting voice reminders for taking medicines on time

- Reading out text after pointing at signs/documents

- Giving weather warnings and updating on local news

There will be opportunities here for news organizations to develop voice-specific experiences for these users, helping to educate and inform them of the world they live in. Considering the huge scale of potential audiences that could be tapped into as a result, it offers a huge opportunity to those news organizations positioned to work on this. This is an area I’ll continue to explore in personal capacity in the coming months — do get in touch with me if you have ideas.

Relationship status: It’s complicated

Voice interfaces are still very new and as a result there are ethical grey areas that will come more to the fore as they mature. One of the most interesting findings from the NPR-Edison research backs up other research that suggests users develop an emotional connection with these devices very quickly — in a way that just doesn’t happen with a phone, tablet, radio or TV. Users report feeling less lonely and seem to develop a similar emotional connection to these devices as having a pet. This tendency for people to attribute human characteristics to a computer or machine has some history to it, with its own term — the ‘Eliza effect’, first coined in 1966.

What does that do to the way users then relate to the content that is shared to them through the voice of these interfaces? Speaking at recent event on AI at the Tow Center for Journalism in New York, Judith Donath, from the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard explained the possible impact: “These devices have been deliberately designed to make you anthropomorphize them. You try to please them — you don’t do that to newspapers. If you get the news from Alexa, you get it in Alexa’s voice and not in The Washington Post’s voice or Fox News” voice.”

Possible implications for this could be that users lose the ability to distinguish from different news sources and their potential editorial leanings and agendas — as all their content is spoken by the same voice. In addition, because it is coming from a device that we are forming a bond with, we are less likely to challenge it. Donath explains:

“When you deal with something that you see as having agency, and potentially having an opinion of you, you tend to strive to make it an opinion you find favourable. It would be quite a struggle to not try and please them in some way. That’s an extremely different relationship to what you tend to have with, say, your newspaper.”

As notification features begin to roll out on these devices, news organizations will naturally be interested in serving breaking news. However, with the majority of these smart speakers being in living rooms and often consumed in a communal way by the whole family, another ethical challenge arises. Elizabeth Johnson from CNN highlights one possible scenario: “Sometimes we have really bad news to share. These audio platforms are far more communal than a personal mobile app or desktop notification. What if there is a child in the room; do you want your five year old kid to hear about a terror attack? Is there a parental safety function to be developed for graphic breaking news content?”

Parental controls such as these are likely to be developed, giving more control to parents over how children will interact with these platforms.

One of the murkiest ethical areas will be for the tech platforms to continue to demonstrate transparency over: with the “always listening” function of these devices, what happens to the words and sounds their microphones are picking up? Are they all being recorded, in anticipation of the “wake” word or phrase? When stories looking into this surfaced last December, Amazon made it clear that their Echo speakers are been designed with privacy and security in mind. Audience research suggests, however, that this remains a concern for many potential buyers of these devices.

Voice AI: The ethical dimension

- Kids unlearning manners

- Users developing emotional connections with their devices

- Content from different news brands spoken in the same voice

- Inappropriate news alerts delivered in communal family environment

- Privacy implications of “always-listening” devices

Jumping out of boiling water before it’s too late

As my Nieman Fellowship concludes, I wanted to go back to the message at the start of this piece. Everything I’ve seen and heard so far with regards to smart speakers suggests to me that they shouldn’t just be treated as simply another new piece of technology to try out, like messaging apps, bots, Virtual and Augmented Reality (as important as they are). In of themselves, they may not appear much more significant, but the real impact of the change they will herald is through the AI and machine learning technology that will increasingly power them in the future (at this stage, this is still very rudimentary). All indications are that voice is going to become one of the primary interfaces for this technology, complementing screens through providing a greater “frictionless” experience in cars, smart appliances and in places around the home. There is still time — the tech is new and still maturing. If news organizations strategically start placing bets on how to develop native experiences through voice devices now, they will be future-proofing themselves as the technology rapidly starts to proliferate.

What does that mean in reality? It means coming together as an industry to collaborate and discuss what is happening in this space, engaging with the tech companies developing these platforms and being a voice in the room when big industry decisions are made on standardising best practices on AI.

It means investing in machine learning in newsrooms and R&D to understand the fundamentals of what can be done with the technology. That’s easy to say of course and much harder to do with diminishing resources. That’s why an industry-wide effort is so important. There is an AI industry body called Partnership on AI which is making real progress in discussing issues around ethics and standardisation of AI technology, among other areas. Its members include Google, Facebook, Apple, IBM, Microsoft, Amazon and a host of other think tanks and tech companies. There’s no news or media industry representation — largely, I suspect, because no-one has asked to join it. If, despite their competitive pressures, these tech giants can collaborate together, surely it is behoven on the news industry to do so too?

Other partnerships have already proven to have been successful and form blueprints of what could be achieved in the future. During the recent US elections, the Laboratory of Social Machines at MIT’s Media Lab partnered with the Knight Foundation, Twitter, CNN, The Washington Post, Bloomberg, Fusion and others to power real-time analytics on public opinion based on the AI and machine learning expertise of MIT.

Voice AI: How the news industry should respond

- Experiment with developing apps and skills on voice AI platforms

- Organize regular news industry voice AI forums

- Invest in AI and machine learning R&D and talent

- Collaborate with AI and machine learning institutions

- Regular internal brainstorms on how to use voice as a primary interface for your audiences

It is starting to happen. As part of my fellowship, to test the waters I convened an informal off-the-record forum, with the help of the Nieman Foundation and AP, bringing together some of the key tech and editorial leads of a dozen different news organizations. They were joined by reps from some of the main tech companies developing smart speakers and the conversation focused on the challenges and opportunities of the technology. It was the first time such a gathering had taken place and those present were keen to do more.

Last month, Amazon and Microsoft announced a startling partnership — their respective voice assistants Alexa and Cortana would talk to each other, helping to improve the experience of their users. It’s the sort of bold collaboration that the media industry will also need to build to ensure it can — pardon the pun — have a voice in the development of the technology too. There’s still time for the frog to jump out of the boiling water. After all, if Alexa and Cortana can talk to each other, there really isn’t any reason why we can’t too.

Nieman and AP are looking into how they can keep the momentum going with future forums, inviting a wider network in the industry. If you’re interested, contact James Geary at Nieman or Francesco Marconi at AP. It’s a small but important step in the right direction. If you want to read more on voice AI, I’ve been using the hashtag #VoiceAI to flag up any interesting stories in the news industry on this subject, as well as a Twitter list of the best accounts to follow.