This post was originally published by Ken Doctor for Harvard’s Nieman Lab.

Led by the cofounder of Square, Invisibly promises “four-figure CPMs” and a way to make big money off readers who won’t subscribe. It says it has most of the U.S. digital news industry on board. But is it just “an ad network dressed up as a savior for news sites”?

Oh no, can it be another news micropayments play?

With the seemingly sudden sense that there have got to be ways other than a full-bore subscription for readers to help pay the freighted costs of producing news, 2018 will bring multiple bold new efforts to revive the news business.

Now you can add a new venture, Invisibly, to that list. But its ambitions are far bigger than just micropayments — or just the news business.

Jim McKelvey, the cofounder of Square, spearheads and funds Invisibly. He’s spent almost a year and a half talking to media brands big and small, entertainment and news. And he’s talking about a venture he says could generate a billion dollars a month in new revenue largely for those companies. Already, I’m told, “hundreds” of titles, including newspapers, magazines, and other media, have signed up to test Invisibly, which joins Scroll, LaterPay, and Blendle in offering newer payment models for content.

While Invisibly’s website launched a month ago, it has been the news industry’s best-kept secret, morphing over time from “The McKelvey Project” or just “McKelvey” in publisher shorthand. Despite a well-received presentation at the SNPA/Inland conference in September and innumerable talks between Invisibly staff (now numbering 15) and media executives, public word of Invisibly hadn’t leaked.

The company still won’t speak publicly, but in more than a dozen interviews, I’ve been able to piece together some visibility into this innovative model.

Yes, Invisibly is a micropayments company in some ways, but it believes that a newer kind of advertising engagement will generate most of its revenue. McKelvey — who along with cofounding the mold-breaking mobile payment company is also board member of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis — makes a pitch that is more complex and more cerebral.

He’s talked about “building a new business-model stack” for media industries. That’s makes supreme sense to those in the tech industry and remains a bit of a head-scratcher to many of those in traditional publishing.

In fact, in Invisibly’s stealth launch — with a product that will begin testing soon into the new year — we can see a clash of civilizations. There are the old newspaper and magazine companies, long grasping onto a binary subscribe/don’t subscribe model, even in the decade-long shift to digital paywalls. Then, there’s Silicon Valley’s blow-it-up, rethink-it-from-the-bottom-up approach to business disruption and business building.

McKelvey, 52, has found what all technology companies have found in pitching the press and wider media: It’s agonizingly slow going, no matter how good a deal you may be offering. This super-confident Renaissance man can seem like a character out of HBO’s “Silicon Valley” to publishers, talking about his self-made net worth, his boundary-breaking background, and his mode of travel (“private jet” and “self-driving car” come up, publishers say). He’s a self-made man in a hurry to develop Big Ideas. In taking on the media business conundrum in the digital age, he’s acting on his LinkedIn tagline: “I enjoy solving problems in almost any area.”

With Invisibly, his focus has turned to creating a new way forward for high-quality news and entertainment. In presentations, he can decry the world of mediocre content — news and entertainment — that shows signs of winning against higher-quality, more expensive-to-produce content. The solution, he believes, is finally finding new ways to support high-quality digital content creation.

As he presents what can seem like a blizzard of ideas, he has managed to impress executives enough to get some signed up for a test.

One such publisher spoke for several others with whom I talked — almost all of whom wanted to remain anonymous — with this assessment of the project: “Honestly, I’m not that invested in knowledge about what he’s doing. I’ve seen the pitch and most everyone says the same thing: ‘He’s a bit arrogant. He’s been very successful.’ It costs nothing to say ‘sure, go ahead,’ and if it works, we’ll most likely be in.’”

In his relentlessness — and, importantly, in his ideas — McKelvey has managed to convince dozens of top-drawer names to test Invisibly. Those names, according to company communications, include: McClatchy, Gatehouse, The Dallas Morning News, Hearst Newspapers, The Atlantic, The Motley Fool, and Warner Brothers.

How would Invisibly work?

So what is this “new business model stack”?

To put it simply, Invisibly attempts to move publishers beyond that subscribe/don’t subscribe model. As with the concepts of Scroll and LaterPay, Invisibly acts on this principle: Something like 2 percent of a digital audience will buy an all-access subscription, but there’s another group will pay for high-quality content in other ways. The trick in reaching them: offer more choices.

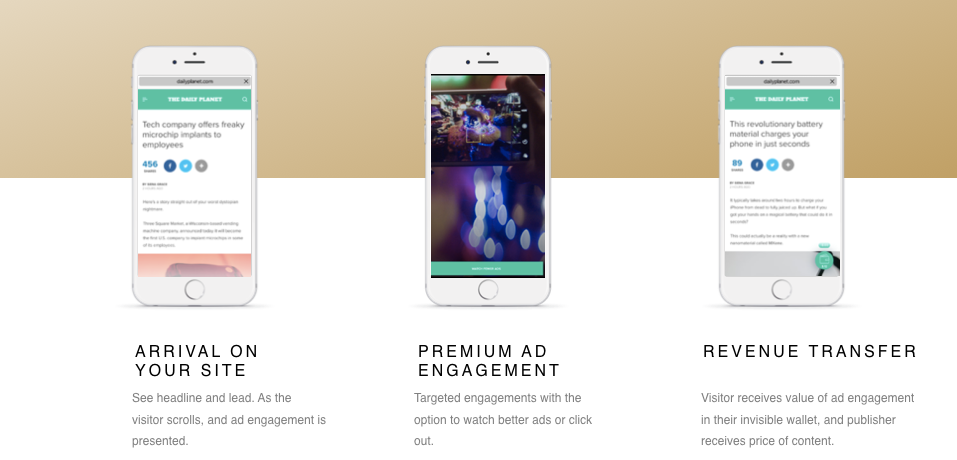

So Invisibly will offer essentially two kinds of choices to non-subscribing visitors to paywalled sites.

If a publisher wants to offer access beyond its set number of free stories a month (one of the most common metered models), it can offer payment per article, day passes, or week passes.

Or the publisher can pop up an Invisibly-served video ad. Watch the ad or answer a few questions, and you get access to the site for a set amount of time. How much? That’s TBD.

In both cases, a user’s current status is tracked through an invisible digital wallet that records how much she’s spent on content and how many ad engagements she’s had. Here’s how the company describes it:

A digital wallet will accompany visitors as they navigate content across the internet. As the visitor happens upon participating sites, the digital wallet will invisibly keep a ledger of earnings from brand engagements and expenditures from content. At the optimal time, the system will prompt visitors to sign up and improve their experience, by giving them a choice of watching or avoiding ads. If a visitor wants to avoid ads, they can add payment (i.e. a credit card) that can process all of their content and subscription purchases in one bill.

A specific revenue promise is a big part of why early testers have signed up. Invisibly promises, by contract, that those who have already signed up will keep all the micropayment and ad revenue, in perpetuity. Some time before launch, Invisibly will begin to take its own revenue share (“over 20%”) for companies that aren’t launch partners. That ability to keep revenue — and the ability to opt out of Invisibly some time before launch without apparent penalty — has built Invisibly’s list of partners.

Invisibly brags on its site that it has “verbal commitments from US digital content publishers representing 73% of the industry and we are actively transitioning these to signed contracts.”

While micropayments will be a key feature of the Invisibility partnership for news publishers with paywalls, that may end up being a small part of the initiative. Consider that much of the news web is still free, from CNN and NPR to BuzzFeed, Vox, Vice, and thousands of other sites. In fact, while preserving higher quality news sources is a key McKelvey goal, it’s the big entertainment companies, like a Disney or a Warner, that would be much bigger parts of the Invisibly network. In that regard, Invisibly could mount an alternative to paying Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon for some video content.

For those seeking new ways to satisfy advertisers, McKelvey says he’s figured out a new way to do that.

In a video on his site, he makes his pitch: “The advertiser experience in our system is going to be unlike anything you’ve seen before…The ad load is going to decrease by orders of magnitude, replaced with fewer, better engagements…Instead of interrupting users, you can engage them…For 20 years, the world has treated online advertising like it was print or television. But the web is a two-way medium, so let your customers talk back. Let them engage. But you can only do this with their permission. Which is what we’re going to get you. Once you have someone agreeing to engage with your brand, you can truly communicate your message. And it’s a lot more fun.”

Fun, and lucrative. Publishers could receive ad rates an “order of magnitude — three to four-figure CPMs” — greater than current, run-of-the-mill advertising, goes the pitch.

McKelvey eschews the world of interrupting bothersome ads — the same bugaboo recognized by Tony Haile’s Scroll, though addressed quite differently. McKelvey intends to make a new kind of peace between advertisers and consumers.

In this worldview, it’s not advertising per se that’s the problem — it’s the way digital advertising has worked. McKelvey has enlisted WPP, the multinational ad giant, as a partner as Invisibly starts up. In addition, its website includes such “supporters” as the Omnicon Group, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Procter & Gamble.

Can he offer a kind of advertising that consumers will more willingly engage in — watching a video, answering a few questions, identifying their buying wants — rather than being blitzed with intrusive pitches for things they aren’t remotely interested in?

It’s not just the ad presentation that Invisibly hopes will distinguish it. McKelvey tells publishers that part of his secret sauce lies in harnessing the power of ad tech. His pledge to media companies: I’ll make it work for you.

Invisibly says it uses the ad-targeting intelligence of the web to help media better target consumers. In presentations, McKelvey has acknowledged that such targeting can seem “creepy,” but explains it’s already the world that we — consumers and media executives — live in. Better to apply that intelligence to supporting high-quality content than not.

Consequently, Invisibly wants to use such targeting to perfect both advertising offers and micropayment offers, based on its knowledge of individual, browser-driven behavior. If consumers find themselves in the market for a new truck, or for more information about family health, Invisibly would, in theory, would take that knowledge and offer them a more relevant digital experience.

That approach isn’t a new one. In fact, as I’ve covered the serial reader revenue innovations of the Financial Times, McKelvey’s model sounds a lot like that of the FT. “Propensity modeling” is the term for it — understanding the likelihood of how a consumer is likely to respond, or not, to a subscription offer. Or to a newsletter offer, or to the opportunity to answer a Google Survey question. It’s a value exchange: money or attention paid in exchange for content.

In one grand way, then, it seems like Invisibly is taking the FT’s long-developed strategy and trying to apply it widescreen on the web. The promised land: divining enough of user identity, via ad tagging, to tell the publisher enough about the non-paying visitor (which, for most, is nearly all of them) so that Invisibly can serve the right offer (micropayment, subscription, newsletter, ad) in real time to each individual browser-known user.

While media companies are willing to test, how much will they trust in this would-be ubiquitous system? They like the idea of potential new revenues, but have some fundamental questions.

If they believe that reader revenue really has become the lifeline of the serious news business, then does offering would-be payers preroll ads get in the way of that path forward? Faced with a choice of paying something — an article fee, a timed pass, or a subscription — or simply watching an ad, will the great majority of would-be payers simply opt to watch? That’s one concern I’ve heard. Says one publisher who has declined the deal: “In short, our impression was that this is basically an ad network dressed up as a savior for news sites.”

Further, McKelvey’s reliance on user behavior signals a question about the other big digital currency: data. While each media partner would presumably have access to all its own related data, Invisibly would be building one of the biggest human-behavior data banks extant if it achieves its ambitions to sign up thousands of well-trafficked sites. What value might that provide, and to whom when?

And no matter how good these ideas are, how will they translate with actual publisher implementations? McKelvey and his team will undoubtedly try to make the publisher implementation as easy as possible, but what new kinds of frictions, new interruptions in reading, might follow as Invisibly actually gets put on sites?

What will the readers think?

Then, there’s the big — and at this point unanswerable — question of consumer acceptance and adoption.

A reader/consumer’s “wallet” will fill up silently in the background — invisibly, you might say — depending how much value his attention to commerce is affording advertisers. Consumers won’t see these wallets, or how much content these value holders will offer them. Why? In showing actual value gained, consumers will try to “game” the system.

If, though, there’s enough currency in those wallets, presto, magico, they’re granted additional access to content without paying for it in cash. At first hearing, that seems like a semi-transparent transaction — will users be okay with that?

And how much do readers really want to actively engage with ads, anyway? McKelvey would probably be the first to tell you that’s unpredictable. That’s why I understand Invisibly could continue its testing of consumer behavior for as long as a year.

Certainly, readers might respond better to better ads, but the practicality of that targeting raises dozens of questions about execution — and consumer adoption. Will the ads, questions, or micropayment asks that Invisibly will pop up seem logical to consumers? Or will they seem like new frictions in the process of consuming news or entertainment?

Consumers won’t have to sign up for or sign into Invisibly, as they’ll have to do with Scroll. That’s where the invisibility of Invisibly derives. Background targeting — that mastery of ad tech to benefit media companies — identifies them. The system “fingerprints unique individuals, irrespective of properties. Each user carries enriched 1st party data based on consumption, context, behavior and user profile,” says Invisibly’s site. “Creepy,” or just the way we are now?

If consumers do sign up with Invisibly — and they’ll be offered the chance to sign up through small linked Invisibly logos on media sites — that signup will provide Invisibly more targeting knowledge. And that would increase the value of that signup to advertisers, and thus cash to content producers.

The company itself

So where does Invisibly the company fit in here?

McKelvey has painted it as a self-funded, mission-driven company, one aimed at recovering lost value for media brands in the age of digital platform disruption and distortion.

It’s a for-profit company, 51 percent owned by a trust, and that trust is controlled by McKelvey. It’s a setup intended to keep the company independent, he’s told media executives. It couldn’t, he says, under that structure be subject to takeover (presumably hostile) from a Murdoch, Zuckerberg, McAdam, or Page.

Jim McKelvey’s company is something of a black box to media executives. But they’re intrigued.

“To be honest, we do not know enough about the tech integration to know how it will work. At this time, we are signed up for the test and will participate,” Grant Moise, The Dallas Morning News’ general manager, told me. He added:

What I can share with you is what I like about Jim McKelvey’s approach. He is being bold enough to know that the digital display advertising model is broken. CPMs are eroding due to the multiple challenges associated with digital display advertising at its core (viewability, bot fraud, etc.). The approach of devising a new model where the publisher, the advertiser, and the consumer all benefit from a strong user experience is sorely missing in the digital age.

While most publishers (including us) have shifted from a digital advertising focus to a digital subscription focus, I am glad to see that someone is trying to challenge the thinking that these have to be mutually exclusive.