This article originally appeared on digital HKS’ Medium.

A variety of centers and individuals have tried to define Public Interest Technology (PIT) and those working to advance it. Sasha Costanza-Chock of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), echoing how many refer to Public Interest Law, defines PIT as “people working to use technology for social good and for social justice.” New America uses a similar version of Costanza-Chock’s definition. They describe the PIT as efforts “dedicated to leveraging technology to support public interest organizations and the people they serve.”

In terms of PIT practitioners the Berkman Klein Center at Harvard casts them as “people who understand technology and who work in the public interest.” Michael Brennan of the Ford Foundation broadens that characterization by defining PIT practitioners as those who “use technology skills to fight for the greater public good.”

These somewhat amorphous definitions and practitioner descriptions hinder the cataloging of PIT-specific initiatives. Adopting some of these definitions would make just about everything related to technology at Harvard a PIT initiative. Most faculty believe their work is in the public interest and many, if not all, use technology to some degree.

As pointed out by numerous PIT stakeholders we’ve engaged, a lack of specificity makes it more difficult to identify PIT work as well as to distinguish it from more recognizable technological and public interest work.

Defining PIT requires more narrowly defining the public interest as well as technology. Technology refers specifically to digital technology. And the level of digital technological skills has a clear, if sometimes hard to pin down, spectrum. For example, there’s an obvious difference in the “hard” technology skills of a developer versus the “softer” skill of using Excel.

Like technology, public interest is similarly hard to pin down, although it typically means serving a collective good be that preserving it or advancing it via a tangible service (working for government or a mission driven non-profit) or advancement of a right or norm (creating safe space for dialogue or preventing unwarranted surveillance). But here too there is a difference between “deep” expertise and knowledge — of studying and creating systems of governance, or — and a more “shallow” awareness that governance or policy matters.

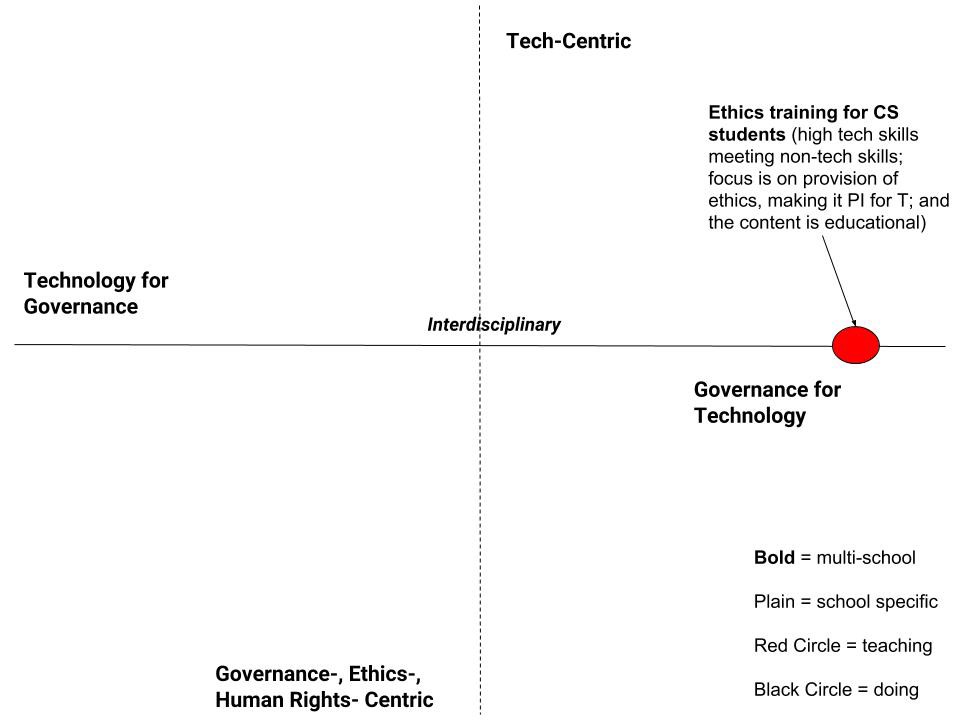

There is a long history at Harvard of thinking about technology and the social sciences. Back in the 70s and 80s, Harvey Brooks, who served as the Director of the Science, Technology, and Public Policy Program of the Belfer Center at HKS, talked about two balancing subcategories: science for government and government for science. Brooks’ idea was that science could help governments fulfill their mission and create public goods, and that governments could enable science through funding and regulation. Most recently, Ash Carter, the current Belfer Center director, updated Brooks’ phrase and applied it to the Center’s Technology and Public Purpose (TAPP) project; they refer to technology for governance and governance for technology.

With this map in place, it takes us a small step away from a binary distinction of either being PIT or not being PIT but recognizes the diversity of programs, people and skills active in the space. For instance, Joshua Feldman’s work exemplifies technology for governance. Feldman, a student in the Master of Data Science program, is creating opportunities for students to apply their digital technology skills to public interest organizations such as nonprofits and governments through summer internships. On the other side, governance for technology looks like Barbara Grosz’s embedded ethics program, where ethicists are embedded in computer science classrooms to teach ethics alongside the regular curriculum.

Our conception of Public Interest Technology hinges on interdisciplinary as evidenced by our map. PIT is about the marriage of “hard” technology skills with knowledge in other domains related to the public interest and governance.