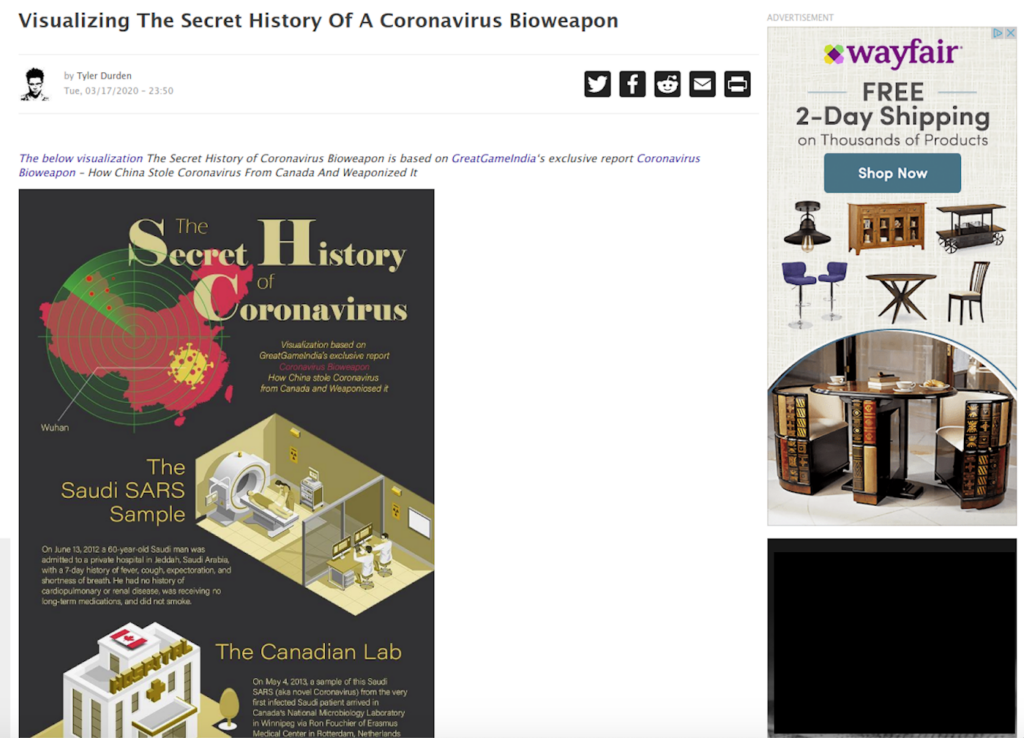

A Wayfair advertisement appears alongside a conspiracy theory around the origins of the COVID-19 coronavirus (screenshot by Lucas Wright).

If any of several anonymous websites are to be believed, the mainstream media isn’t telling us the truth about the coronavirus COVID-19 sweeping the globe. They allege that COVID-19 was incubated in a Canadian laboratory and was smuggled out of the country by Chinese scientists intent on developing it into a mass biological weapon. What the entirely unfounded allegations lack in proof, they make up for in lurid details: names are named with photos attached. Next to one story that purports to reveal the “secret history of coronavirus” is a slick banner ad for Wayfair, the online furniture company.

For the first time in 2019, digital advertising — once just a roundoff error compared to huge television ad budgets — made up more than 50% of global advertising spending. Prior to the rise of the current worldwide pandemic and associated economic downturn, media company GroupM estimated that $326 billion would be spent on digital ads this year, with most of that market captured by Google and Facebook. To meet the needs of the explosive growth in online advertising over the past decade, the ad-tech ecosystem grew along with it, offering services that brands and agencies use to manage their digital presence. In the name of optimization, intermediaries called “ad exchanges” sprung up to handle website ad placements on behalf of their customers. Programmatic advertising — the use of software to buy and sell ad space — means that brands typically no longer exert control over where their ads appear on the web. Much of the time, that level of abstraction is helpful, but in some cases, it becomes extremely problematic.

“the use of software to buy and sell ad space means that brands typically no longer exert control over where their ads appear on the web.”

In the case of coronavirus conspiracy theories, the motivations of the content creators vary from ideological to political. A major (and occasionally overlooked) portion of these creators are financially motivated. They seize upon hot-button issues like COVID-19 and produce inflammatory content, knowing that it is more likely to be engaged with and shared. Then, they post it on a website, waiting for visitors to roll in. If the site is registered with one or more ad exchanges, brands will automatically bid against each other for prime digital ad locations: an auction that takes place in a matter of milliseconds. Without any regard to how the content aligns with a brand’s values, ad exchanges make payments to the host sites based on number of views and audience characteristics. Visitors from certain parts of the world, like the United States, are more valuable than others; the cost per one thousand page views could range anywhere from a few cents to several dollars. The Global Disinformation Index estimates that each year, a quarter of a billion dollars goes toward the funding of disinformation websites.

A Credit Karma advertisement appears with coronavirus content published by a white supremacist forum, called “the first major hate site on the Internet” by the Southern Poverty Law Center (screenshot by Lucas Wright).

Why is this a problem? For one, false information is often harmful. The COVID-19 crisis alone has spawned multiple potentially life-threatening narratives, such as that the virus can be killed by gargling with salt water, or that it is caused by the installment of 5G cellular networks. If we want to reduce the total amount of disinformation online, we need to avoid making it profitable.

On a more pragmatic level, appearing in advertisements next to dangerous and inaccurate articles is bad for business. Consumers today are demanding more from the companies whose products they use, including social responsibility. The activist organization Sleeping Giants began with a crowdsourced campaign to get advertisers to pledge not to show ads on Breitbart, the far-right news and opinion website. As of this writing, more than 4,000 companies have made that pledge, presumably because they did not want their brand associated with that type of content. Advertiser-led initiatives, like the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM), are trying to promote collective action by members to combat harmful content like disinformation.

“each year, a quarter of a billion dollars goes toward the funding of disinformation websites.”

The biggest online ad exchanges include some of the biggest and wealthiest companies in the world, among them Google, Amazon, and Xandr (a division of AT&T). Rather than waiting for activist groups to call out their customers, exchanges should take a more proactive approach in ensuring that no sites spreading disinformation are among their target ad locations. Although they could see their revenue decrease slightly, a staunch, industry-wide refusal to monetize false information would limit advertisers’ exposure to controversies; raise the barrier to entry for producing and disseminating disinformation; and reduce the spread of inaccurate narratives. This shift would require a coordinated effort on behalf of companies and other stakeholders — including users — who should demand that these companies are held accountable. Such a gesture would not only improve the quality of public information and discourse but, especially in the time of a global health crisis, could be literally life-saving.