Humans versus robots: When we take performance tracking too far

Amazon has experimented with a variety of tracking systems for warehouse employees, including tracking wristbands and automated termination. What are the human costs of these systems, and how can they be best corrected?

Quotas are not new. In the United States, Frederick Taylor introduced “scientific management” into manufacturing in the late nineteenth century, in many ways laying the groundwork for modern-day people analytics in manufacturing and logistics. [1] Taylor was controversial in his day, and the controversy continues with good reason. With better technology, companies are able to take people analytics to the next level through automated, real-time tracking and data analytics systems designed to optimize employee productivity.

These approaches can be powerful, but what are the human costs?

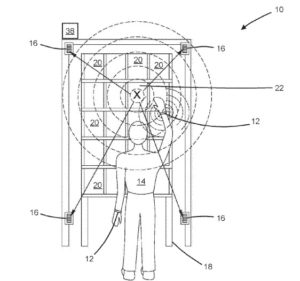

Like many companies, Amazon has long tracked the productivity of its warehouse employees, but the company has faced increasing criticism for taking these systems too far. Two years ago, Amazon patented wristbands that can track and guide employees’ motions through the use of sensors and haptics. [2] Additionally, Amazon has implemented a system that tracks employees’ productivity and “time on task” and automatically generates warnings when targets are not met. If the employee continues to miss targets, the system automatically generates termination paperwork and notifies a manager. Amazon states that managers have the final say in whether to terminate the employee, but productivity records suggest that workers are routinely let go based on productivity issues highlighted by their tracking system. [3]

Privacy: First, employees feel like they are being watched at all times. They cannot ever slow down, out of fear of being dinged for time off task. While employers certainly have a right to track employee productivity and ensure that standards are met, tracking employees at all times with such a punitive system in place creates a culture of fear that drives high turnover and workplace accidents, not to mention an overall miserable experience for employees. Ultimately such practices will hurt productivity due to employee turnover and low morale.

Transparency: These tracking systems are also not transparent, which makes them different from sales quotas and similar incentive systems. Workers have little information about the algorithms and managerial decisions that determine the quotas. Amazon has every incentive to speed up work, and partly due to the culture of fear, employees have no reason to trust that the standards have been fairly established with worker well-being in mind.

Respect: Last, and worst of all, the system dehumanizes management. Amazon warehouse employees have often been quoted saying they feel that Amazon treats them like robots, and it’s not difficult to understand why. Automating warnings and termination paperwork disincentives managers from engaging with their team as people and providing adequate support or training. In other contexts, managers are able to consider personal and circumstantial context when determining whether to give an employee a warning or terminate them. For example, is this person dealing with a difficult issue at home? Was there a particular challenge facing the team? Automating this judgment may seem more objective, but it does not account for the many other factors that go into the productivity of a worker besides his or her competence and work ethic.

How could Amazon use this data to achieve better results, while respecting employees?

Tracking data could be anonymized and reviewed by managers at a warehouse or team level, giving managers incentives to engage with employees and understand what is and is not working. Amazon could also use the anonymized data to experiment with different layouts, collaboration techniques, and communication systems. Outcomes could be tied to upside, rather than termination. Most importantly, feedback could be delivered in a human way, and terminations should be managed by humans and not computers.

Sources:

[1] For a good background on Taylor, see the HBS case on his work. This case is taught as part of The Coming of Managerial Capitalism: Thomas McCraw, “Mass Production and the Beginnings of Scientific Management, Harvard Business School, June 20, 1991, https://store.hbr.org/product/mass-production-and-the-beginnings-of-scientific-management/391255.

[2] The New York Times, February 1, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/technology/amazon-wristband-tracking-privacy.html?searchResultPosition=9

[3] Julie Bort, “Amazon’s warehouse-worker tracking system can automatically pick people to fire without a human supervisor’s involvement,” Business Insider, April 25, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-system-automatically-fires-warehouse-workers-time-off-task-2019-4.

Colin Leacher, “How Amazon automatically tracks and fires warehouse workers for ‘productivity’,” The Verge, April 25, 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/25/18516004/amazon-warehouse-fulfillment-centers-productivity-firing-terminations.

[4] Will Evans, “Ruthless Quotas at Amazon Are Maiming Employees,” The Atlantic, December 5, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/11/amazon-warehouse-reports-show-worker-injuries/602530/.

Image credit: Ruchindra Gunasekara on Unsplash

Thank you for this summary! I also feel uncomfortable with this technology, and I appreciate the 3 buckets you’ve used to summarize potential points of discomfort.

However, I do question this statement: “Ultimately such practices will hurt productivity due to employee turnover and low morale.” This could, in theory, be proven or disproven by looking at actual employee turnover data and surveys of morale – and my hunch would be that Amazon has crunched the numbers, since that’s what Amazon does, and they keep using the technology despite widespread ethical concerns (and the resulting PR nightmare) because they’ve found that turnover and morale aren’t problematic enough to offset the gains in efficiency from using the tracker.

Ultimately I suspect that it won’t be pure economics that convince Amazon or other companies to abandon these technologies.

I really appreciate your thoughts here, and completely agree that some form data anonymization should be necessary (assuming the anonymization process is robust enough that employers are not be able to re-identify the individuals). I also agree that having a human in the loop is a critical aspect that is missing!

Your post also made me wonder how successful this tracking was in terms of increasing the percentage of quotas met (which I assume was their initial goal). In a class I took at the Kennedy School, we talked about the gift-exchange game, which attempts to model the relationship between employers and employees. Experiments conducted about this game typically consists of three different treatments: (1) Trust treatment: The employer offers a wage, w, and expects an effort, e, in return from the employee. There is no enforcement of the expected effort in this treatment. (2) Penalty treatment: The employer offers a wage, w, and expects an effort, e, in return from the employee. In this instance, the employer can monitor the employee’s effort and institute a penalty for shirking. (3) Bonus treatment: I will not go into those details here, as they are not relevant to my point. Results of these experiments have shown that there is not a statistically significant difference between the amount of employee effort exerted in each of these two treatments (trust vs. penalty). Or, in other words, monitoring employees does not increase their effort/production. I am sure there are instances where this is not always the case, but I found it interesting to think about in this context!

You raise some really interesting points! I couldn’t agree with you more when you say “Last, and worst of all, the system dehumanizes management”. I think this is a growing and pressing issue when it comes to incorporating new technology into people analytics practices. Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should. I also think we’re not knowledgeable enough about the implications (particularly 2nd and 3rd order effects) of using such technology. I’d really like to see a transparent analysis of the benefit of using these technologies against the costs – and would guess they’d be marginal to null. I think using these kinds of technologies are really hard to explain to employees as anything more than trying to get them to work harder, faster, and better – more like machines and less like humans.

Thank you for your thoughts, Meg! I’m also very concerned about how they use this technology. One other context that makes this technology even worse is Amazon’s warehouse policy. There is a quitting bonus for warehouse employees, which is a one-time payment starting from $2000 with an increase of $1000 up for each year the employee stays with the company until it reaches $5000. The thing is, Amazon opens up the quit window once in every year, right after the peak winter season, and those who accept this quit offer can never work at Amazon again (even as a part-timer).

So I think what happens is that they track down the low-performers, and instead of giving them a proper training or other chance, they soak out those low-performers right after the peak season and replace them with new hires with starting salary.

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/21/why-amazon-pays-employees-5000-to-quit.html

Thank you for the interesting read, Meg! I couldn’t agree more with the main areas of concern that you highlighted (privacy, transparency, and respect). In addition to cost-cutting and safety, I tried to push myself to think of another way management could justify leveraging “scientific management” in this way. In doing so, I was reminded of a book that we had to read in Leadership and Happiness titled ‘Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion.’ I think the author might argue that terminating under-performing workers might be the “compassionate” thing to do as their employment is simply not a good fit. In other words, the employee would be better off, and presumably happier, at a different employer. Obviously, one has to make some pretty serious assumptions and jump through some hoops to reach this conclusion, but I suppose one might be able to rationalize “scientific management” in this manner. Given the “pros” and “cons,” I feel like Jeff Bezos needs to take a page from LCA’s playbook and outline the legal, ethical, and economic responsibilities of Amazon. I would hope that after doing so, he would realize that using this technology to automate terminations is a terrible call.

Thank you for the article! The automating warnings and termination paperwork sound really bad to me, thinking about how humans could not keep their work straight up all the time. As Prof. Polzer said in the class, people are noisy. Partly, I believe us, the consumers, are also key contributors to this bad working environment. My conflicting feeling knowing this issue is why people still support Amazon knowing this news. I am curious how far could Amazon go using this dehumanized approach? My hypothesis is that if society cares about this, society could pressure Amazon to reconsider its practice. But … this’s far from what I’ve witnesses counting Amazon delivery boxes in Rock Center’s basement.