From Iditarod to the ICU: Transforming Critical Care in Alaska

In Alaska, medication was once delivered across vast distances by dogsled. Now, digital health technologies are reshaping how critically ill patients receive care in America’s last frontier.

The iconic Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race was inspired by the 1925 mission to deliver lifesaving diphtheria medication via dogsled to the remote village of Nome, AK [1]. 90 years later, Alaska still grapples with providing quality, cost-effective care to patients in America’s most geographically dispersed population [2]. Alaska has 14% fewer physicians per capita than the national average [3], and the lack of qualified clinicians often forces critically ill patients in rural areas to be flown to Seattle or Anchorage for care at significant cost [4]. Exacerbating Alaska’s physician shortage is its notoriously challenging weather, which routinely makes medevac flights unsafe.

In 2009, Providence Alaska Medical Center responded to this challenge by introducing eICU, a two-way video and data streaming platform, to care for critically ill patients statewide from its Anchorage monitoring center. eICU critical care physicians (known as intensivists) and nurses remotely monitor patients’ vital signs, laboratory results, and medications in real time, communicating their recommendations to bedside providers. eICU has already lowered costs and improved quality at Providence’s own physical ICU in Anchorage, as well as at several other Alaska hospitals.

Is this an Alaska-only project, or could Providence continue to monetize its expertise at rural hospitals nationwide?

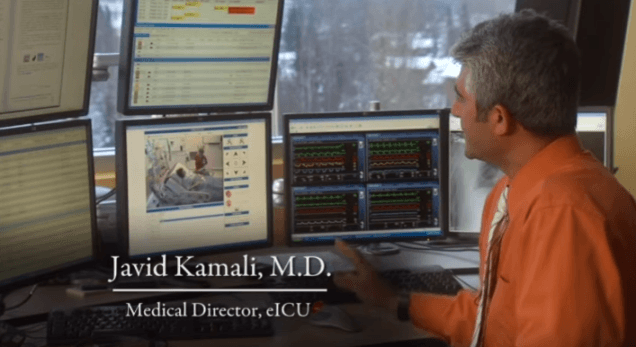

Dr. Javid Kamali, an intensivist (critical care physician), helps care for patients across the state from Providence Alaska Medical Center’s eICU monitoring center in Anchorage (source: Providence Health & Services Alaska).

Improving Providence’s Internal ICU Operations

Before launching eICU for remotely-located hospitals, Providence piloted the system at its own 28-bed intensive care unit in Anchorage. eICU helped Providence achieve:

Improved Nurse Retention

Even in urban Anchorage, few physicians are available in the hospital at night. Before eICU was implemented, if nurses became concerned about patients after hours, they had to phone doctors for counsel. Nurses were reluctant to disturb doctors, who resented the need to make sometimes unnecessary after-hours trips to the hospital to assess questionable patients.

Today, nurses simply contact the after-hours eICU physician on duty, who visualizes patients using high-definition video and orders appropriate therapies. Having 24/7 access to physicians has improved nurse satisfaction and retention—a welcome outcome for an organization that expends $20,000-$60,000 to replace each nurse [5].

Improved Care Quality

In addition to audio/visual capabilities, eICU algorithms monitor patients’ physiologic parameters, including blood pressure, fluid input/output, and lab values. “Smart alerts” trigger eICU staff to notify bedside clinicians to intervene as soon as abnormalities arise. Furthermore, eICU clinicians can double-check hospitals’ compliance with best practices. For example, eICU staff helped Providence improve its frequency of compliance with protocols for ventilator-managed patients from 86% to 98%. Additionally, since eICU’s implementation, Providence has reduced its risk-adjusted ICU mortality rate to 52% below the national rate [6].

Deploying eICU Throughout Alaska

An emergency department clinician at South Peninsula Hospital in Homer, AK, demonstrates the mobile cart that connects his patients with the eICU team in Anchorage (Source: Peninsula Clarion).

Today, Providence provides eICU services to medical centers in Kodiak Island, Juneau, and Homer, AK, none of which have on-site intensivists. These hospitals benefit from the same improvements in nursing retention, care standardization, and patient outcomes that Providence realized at its own ICU. In addition, member hospitals have reduced their patient transfer rates. For example, during Kodiak’s first year in the program, eICU access enabled the hospital to avoid transferring 17 patients, at an average cost of $20,000 per transport [8]. The Kodiak hospital pays Providence $40,000 per year in eICU service fees. It recoups its investment many times over in reduced transfer costs, as well as higher patient care revenues since these patients receive all of their care in Kodiak.

Next Steps

As Providence looks to enhance and expand its eICU business, it should focus on three imperatives:

- Interoperability: The software behind eICU, offered by various vendors, often fails to interface seamlessly with hospitals’ electronic medical record systems, preventing them from realizing or measuring the full benefits of eICU implementation. For example, some hospitals choose between asking nurses to manually enter patient parameters into multiple systems or simply not equipping the eICU monitoring partner with this information [9].

- Physician & Nurse Buy-In: Clinicians have expressed skepticism about the role of eICU programs, with some resentful of being remotely observed, especially when it comes to enforcing standardized care protocols. Leaders at hospitals adopting eICU must be careful to frame implementation as a means of supporting, rather than commanding, bedside providers [10]. Providence can identity and equip new hospital clients with best practices for rapidly earning staff trust.

- Payment Models: Currently, eICU services are funded entirely by client hospitals, without support or reimbursement through patient insurance. Providence should continue to collect data demonstrating improvement in standardization of care, patient outcomes, and costs, and eventually make a case for insurance to contribute to eICU funding.

Although Providence does not own the eICU technology, it can develop a competitive advantage as a rural healthcare monitoring partner to protect its franchise. 90 years after dogsleds delivered the cure to Nome’s diphtheria outbreak, Providence is blazing new trails in Alaska healthcare delivery, and it could serve as a model—or provider—of eICU services for rural hospitals nationwide.

(794 words)

[1] Christopher Klein, “The Sled Dog Relay That Inspired the Iditarod,” History Channel, March 10, 2014, http://www.history.com/news/the-sled-dog-relay-that-inspired-the-iditarod accessed November 2016

[2] U.S. Census Bureau, “Resident Population Data,” https://web.archive.org/web/20111028061117/http://2010.census.gov:80/2010census/data/apportionment-dens-text.php, accessed November 2016.

[3] Association of American Medical Colleges, “Recent Studies and Reports on Physician Shortages in the U.S.,” https://www.aamc.org/download/100598/data/, accessed November 2016.

[4] Jill Burke, “Cure sought for physician shortage,” Alaska Dispatch News, February 17, 2010, https://www.adn.com/alaska-news/article/cure-sought-physician-shortage/2010/02/18/, accessed November 2016.

[5] Providence Health & Services Alaska, “Providence eICU,” YouTube, published May 17. 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=imnYK9fJgnQ, accessed November 2016.

[6] Javid Kamali, MD, Medical Director, eICU, remarks made at Alaska Health Care Commission meeting, Anchorage, AK, June 15, 2012. From transcript provided by Alaska Health Care Commission, http://dhss.alaska.gov/ahcc/Documents/meetings/201206/20121506transcript-2.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[7] Elizabeth Earl, “South Peninsula Hospital installs eICU unit,” Peninsula Clarion, June 18, 2016, http://peninsulaclarion.com/news/2016-06-18/south-peninsula-hospital-installs-eicu-unit, accessed November 2016.

[8] Annie Feidt, “Electronic Intensive Care Unit Expands in Alaska,” Kaiser Health News, March 6, 2012, http://khn.org/news/alaska-eicu/, accessed November 2016.

[9] Robert A. Berenson et al., “Does Telemonitoring Of Patients—The eICU—Improve Intensive Care?,” Health Affairs, August 2009, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/28/5/w937.full, accessed November 2016.

[10] Atul Gawande, “Big Med,” The New Yorker, August 13, 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/08/13/big-med, accessed November 2016.

Hey BJF! Great article – really innovative stuff coming out of Alaska! I appreciate how beneficial this is to a place like Alaska where there are few doctors per resident and a spread out population. However, I can see how this model could be enormously impactful for the American healthcare system as a whole. Almost every state has a shortage of physicians and we are suffering from rapidly increasing healthcare costs and decreasing access to high quality medical services. Could we take this model and extend it as a way to make healthcare more efficient for all Americans? I think the implications of getting this right in Alaska could be huge for the entire population.

I’m surprised Providence rolled this technology out in such an extreme environment. Alaska’s population is so widely dispersed that it seems safer to to use this system in rural contiguous US before full implementation. Regardless, hopefully the citizens are aware of the benefit of this technology. I would guess there are people who are either considering moving closer to bigger towns for better medical care, or choose not to be seen at all due to the inconvenience while their health continues to suffer. This sounds like a great way to ensure doctors/nurses and patients all benefit.