Choosy: Give the People What They Want…To Buy

Solving the billion dollar unsold inventory problem in traditional retail

Why do brands have to guess what I want to buy? What if I could just tell them exactly what I want to wear?

Meet Choosy, an on-demand fashion start-up that leverages machine learning, a team of “Style Scouts”, and crowd-sourced product development to design and produce its direct-to-consumer clothing line. By hashtagging #GetChoosy, Choosy’s users indicate what styles they like[1]. Choosy’s machine learning algorithm and “Style Scout” team then parse this user-generated data and design a product line to be sold on GetChoosy.com. Choosy’s agile supply chain then produces inventory just-in-time (i.e., once an order is placed) and delivers it in ~2 weeks[2].

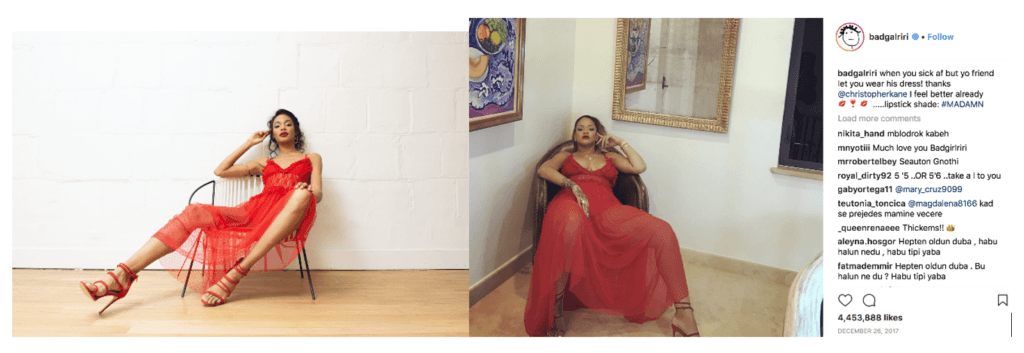

Figure 1. Choosy product (Left) vs. Rihanna Inspiration (Right)[3]

Why is this important?

When it comes to product development, retailers have two Critical Tasks:

Critical Task #1: Predict which styles consumers want to buy

Critical Task #2: Predict how many they want to buy

Failure to deliver on these Critical Tasks results in unsold inventory, which has become a burden to retailers. Unsold inventory results in higher discounts, squeezed margins, inventory holding/disposal costs, and higher COGS. The fashion giant H&M was reportedly sitting on $4.3BN of unsold inventory in March 2018[4].

The fast-fashion retailer, Zara, tried to fix this problem by building a vertically-integrated supply chain, which allowed it to copy and deliver styles directly from the runways to its stores in a matter of weeks. As a result, Zara remained in closer touch with fast-changing consumer trends and it has since benefited from “more frequent shopper visits to stores, fewer sales on markdowns and faster cash conversion cycles” than its competitors with longer production lead times[5]. However, Zara still has to guess which high-fashion styles consumers want and then guess how many they plan to buy, leaving room for waste.

How is Choosy solving this?

Choosy not only takes Zara’s model a step further in multiple ways, but it also recognizes that Critical Task #2 is highly dependent on Critical Task #1. In Critical Task #2, Choosy applied just-in-time production process to Zara’s vertically-integrated supply chain, reducing the amount of guesswork they have to do in forecasting customer demand. However, where Choosy’s true magic happens is around Critical Task #1, where they put the power of product selection in the hands of their users. Instead of relying on in-house designers to create a product line like Zara does, Choosy curates a product line directly based on what their customers chose, reducing the need to predict which styles customers want to buy.

Once Choosy gets this data from consumers, it applies its machine learning algorithm and its team of Style Scouts to curate the final collection. In the near future, Choosy will invest in their machine learning capabilities to decrease their reliance on these Style Scouts, parse customer input data faster and release styles sooner. The closer Choosy can come to an Unsupervised Learning Algorithm, the more sustainable their cost structure will become[7].

There may, however, be an even greater opportunity in Choosy relinquishing even more control over product selection. Choosy is still an Integrator Platform that sits between the “External Innovators” and the “Customers”, where Choosy still plays a role in picking what styles to make. My recommendation would be to transition to a Two-Sided Platform model (e.g., Kickstarter), where users can directly interact with each other. In this model, users can post styles they have seen, and other users can pre-order them. Once a product hits a predetermined threshold set by Choosy, Choosy could help produce them. This model still allows Choosy to leverage its just-in-time production process but would decrease the burden on Choosy to decide which final set of products to make. Choosy can instead focus on optimizing its vertically-integrated supply chain and building an online portal and digital product that is simple and easy to use.

Figure 2. Integrator Platform = Choosy today vs. Two-sided Platform = Choosy tomorrow

Regardless of this business model decision, Choosy needs to invest in building a data- and product-focused culture to attract high-caliber technical talent. From experience, a fashion/lifestyle start-up typically has more difficulty recruiting engineering/data talent than a traditional software start-up simply due to its industry. It becomes even more challenging if you do not invest in building a culture that prioritizes technology, data and analytics from the start.

Looking ahead, I am curious about Choosy’s customer experience (i.e., the trade-off between digital-only and brick-and-mortar). Many direct-to-consumer digital-only players have since built retail footprints (e.g., Warby Parker)[8], which leads me to believe consumers have an enduring desire to experience brands in-person before purchase. Will Choosy buck the trend and skip brick-and-mortar, or can they create a retail concept that allows them to maintain their just-in-time, consumer-driven product development process? What could a retail concept like this look like?

Word Count: 797

[1] Vicky M. Young, “Choosy Secures $5.4 Million Seed Round.” Women’s Wear Daily, May 15, 2018, https://wwd.com/business-news/financial/choosy-secures-5-4-million-seed-round-1202673309/, accessed November 2018.

[2] Choosy FAQ, from Choosy Website, www.getchoosy.com, accessed November 2018.

[3] Melody Hahm, “26-year-old launches Instagram-fueled fast fashion brand.” Yahoo! Finance, July 25, 2018, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/26-year-old-launches-instagram-fueled-fast-fashion-brand-192641410.html, accessed November 2018.

[4] Elizabeth Paton, “H&M, a Fashion Giant, Has a Problem: $4.3 Billion in Unsold Clothes.” NY Times, March 27, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/27/business/hm-clothes-stock-sales.html, accessed November 2018.

[5] Kevin O’Marah, “Zara Uses Supply Chain To Win Again.” Forbes, March 9, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kevinomarah/2016/03/09/zara-uses-supply-chain-to-win-again/#8ee534d12564, accessed November 2018.

[6] Kevin Boudreau and Karim Lakhani, “How to Manage Outside Innovation.” MIT Sloan Management Review Volume 50, Issue 4 (Summer 2009): 69-76.

[7] Willy Shih, “Building Watson: Not So Elementary, My Dear! (Abridged)” HBS No. 9-616-025 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), p. 16.

[8] Michael J. de la Merced, “Warby Parker, the Eyewear Seller, Raises $75 Million.” NY Times, March 14, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/14/business/dealbook/warby-parker-fundraising.html, accessed November 2018.

This article was super interesting! I think one of the pain points for customers is finding what they like and knowing which items to choose out of all options, so Choosy learning what a customer likes and then giving them that is an interesting proposition. However, it seems like the recommendations are relevant at a user-specific level, which makes me hesitant about whether they can turn this concept into a store. Just-in-time production for Zara still means that clothes are taking weeks to get to the store, so if Choosy is creating recommendations based on one person’s browsing, and then extrapolating those preferences to large orders of product, I am not sure that the recommendations will be as spot-on as the direct-to-consumer model. In addition, an in-store experience requires cohesion of message, as customers don’t want to walk in to a store filled with a chaos of color, print, and garment type. Because of these things, I think Choosy’s business model would have to be drastically altered to adapt to a store format, and which could result in the loss of their value proposition.

I think this is a super interesting article on open innovation and machine learning and how they combine together to solve a major problem. I am excited to see how the brand signaling effect plays into how much this specific company can scale up in comparison to the consumer preferences. Further I would be interested in the role of the designer would evolve as the ML algorithm learns more about consumer preferences.

Interesting concept and article. I love that it touches on both open innovation and machine learning. I think the last question you posed about digital vs. brick-and-mortar retail is really relevant – especially as it pertains to fashion. I think part of the beauty of Choosy’s model though, is how well it integrates with our digital lives. I love the concept of scrolling through Instagram, adding a hashtag on a cool outfit, and having a company then mass-produce it. I think it would be hard to translate that model into brick-and-mortar. Cool what they’re doing, hope they keep it up!

Very interesting article! Choosy’s solution to two critical inventory and design problems in retail is very clever. The costs implications of not having to design your own clothing is very compelling.

I wonder whether depending on a specific hashtag in an uncontrolled forum, like Instagram, will make it very difficult to develop a purely machine learning solution. The context of the Instagram post seems important to understand if this hashtag is being used because of the clothing items vs. for an irrelevant purpose (e.g., as a. joke, accident, goes viral for a different reason).

Overall, using open innovation combined with machine learning seems like the future of retail–especially for companies not trying to set trends.

I love this idea! indeed having customers influencing what clothes to produce is super interesting and can help reduce the unnecessary inventory if one manage to produce just the right quantity. not sure though how this concept can be combined with brick and mortar. maybe though 3D printing can be a solution to this.

Very interesting post! To get a better sense of Choosy, I just looked at the company website and saw a close copy of a $500+ Self-Portrait dress that went viral after Meghan Markle wore it. So, in addition to solving problems for the brand, it seems like Choosy can make the customer’s buying experience much more efficient. Instead of the customer seeing a dress on Instagram and then trying to find it or a look-a-like, Choosy simply makes the dress for them. As reliance on open-source innovation increases, I wonder to what extent Choosy will have to contend with potential copyright issues from designers whom they are copying? Does this limit the kinds of open-source requests they can respond to?

This is a really interesting topic that I had never thought about before! In thinking about the open-source innovation Choosy uses, I was reminded of the different “jobs” that each part of the value chain has to perform. In open innovation, the jobs of creativity and design are done by the consumers rather than a company, saving significant resources both from the mere fact that the company is not investing in R&D as much and because the consumer is able to exactly select what they want rather than having the manufacturer guess. However, the job of manufacturing still must be done by that company (not consumers). So I wonder whether seeing an image of the product – before it is produced – will be enough for consumers. Will they trust that it will really look how they want after someone else does the job?