Visa – Leveraging Indirect Network effects

Visa has dominated the payment processing industry for decades, leveraging indirect network effects

How does Visa create value?

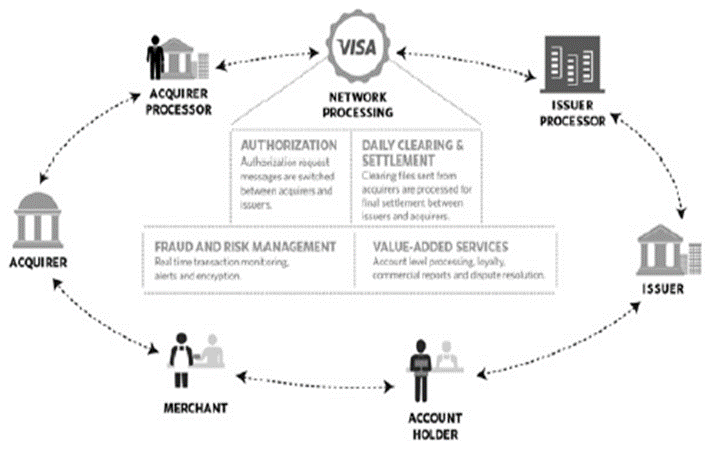

Visa and MasterCard control the most critical aspect of any payment transaction – authorization and clearing using a secure line, thus preventing fraud. In doing so through the use of credit cards, Visa creates value for all stakeholders:

- Merchants: Increases spend amount (allows customers to make impulse purchases, or if they forgot to carry cash), reduces fraud and cash management issues, reduces transaction time, facilitates online shopping

- Account holders: Convenience, security, rewards programs

- Banks (Issuer/acquirer): Additional revenue streams (interchange fees from merchants, late payment fees from account holders)

Visa creates this value by managing a global and reliable processing infrastructure to ensure secure, efficient and safe transactions for merchants and account holders. While the average retail cash transaction is $17, credit card purchases average $70 while debit card purchases average $36 in the US. Cash still accounts for about 85% of global retail transactions, whereas in the US, it is closer to c.50%. There is hence a strong potential for further growth with secular trends towards cashless transactions.

How has Visa remained a dominant player in the segment for 50 years?

There are strong indirect network effects in this segment – as more merchants accept Visa cards, more account holders are likely to use Visa and vice versa. Visa currently has c. 2.9bn cards issued globally, with over 36 million card acceptance points (which is very similar to what MasterCard has).

There is very little differentiation between Visa and MasterCard. The rewards and promotions offered by the issuer (rewards points, cash-back, etc) seem to be a more important consideration for the consumer. Multi-homing of cards is dependent socio-economic strata (credit score) and on the variety of cards offered by the banks that account holders bank with. In spite of the ease of maintaining multiple cards, over 40% of card holders only carried a single brand. Even card holders that carry multiple cards have a strong preference for the use of a single card, driven by the benefits associated with that card. These programs offered by the issuer banks, funded by interchange fees, are designed to increase the switching costs for users, which has been a topic of controversy over the last decade.

On the flip-side, most merchants are forced to accept both Visa and MasterCard cards since the decision on which card to use is driven by the account holder, and merchants are not allowed to price-discriminate users of different network cards in spite of differences in interchange fees, thus obligating multi-homing. This multi-homing on the merchant side has ensured that the market for these payment networks hasn’t tipped, allowing Visa and MasterCard to co-exist with large market shares

The structure of these networks is clustered (most of the transactions are domestic), though that has slowly been changing over the last few decades. This has enabled different market leaders in different local networks (like China’s Union Pay, which claims to have 4.9bn cards in circulation in China, more than that of Visa and MasterCard, even though the transaction volumes and amounts are less)

How did Visa grow the 2 sides of the platform?

The need for simplify the pre-existing practice of revolving credit with merchants that resulted in multiple bills that need to be paid at the end of each month, led to multiple efforts by small banks for unification, that failed in the mid-1950s. Bank of America, with massive resources and presence across California, began massive mailing of around 60,000 ‘unsolicited’ cards in Fresno, California in 1958, as a pilot for a large but concentrated population (of 250,000). This practice continued after the pilot, resulting in over 2 million credit cards by 1959 across California, accepted by over 20,000 merchants, thus creating strong and dense local networks. These unsolicited card drops continued outside of California by banks across the US that licensed this product until 1970 (when they were outlawed), resulting in the issuance of over 100 million credit cards. International licensees in the late 1960s worked on creating local networks of users and merchants.

In more recent years, Visa has explored the option of maintaining a lower interchange fee to attract more merchants to their platform within certain networks and slowly increasing it as the number of acceptance points increases.

How does Visa capture the value it creates?

With global payment volumes in excess of $14 trillion, Visa concentrates on capturing revenues from the merchant side, which is more price inelastic, subsidizing the account holder, who is more price elastic and exercises more choice on the method of payment. It also aims to strengthen the value perception to account holders through strong marketing and branding efforts. Credit card transaction fees are roughly c. 2.5% of revenue, of which 50% goes to the issuer (credit-risk taking party), 40% to the acquirer and 10% to the payment network. Visa has control over setting the inter-change fee to the merchants which is used by the issuer banks in acquiring retaining customers through marketing and rewards programs and has been a topic of controversy.

What are some of the threats Visa faces?

A few companies have tried replicating Visa and MasterCard’s success in the payment infrastructure by building out similar networks over the last 50 years, but not many have succeeded due to the strong network externalities in this market. Successful competitors need to either have a large customer base, existing merchant relationships or both. The way firms have chosen to compete against Visa and MasterCard in the recent past is by bypassing the use of cards (disintermediation), thereby incurring a lower transaction fee, sometimes at the cost of reduced security

Over the last decade, the biggest threat has been payment services that link directly to a user’s account for funds, bypassing the use of a credit or debit card. Paypal (used in c.16% of the transactions) has been a pioneer in digital payments, acting as an acquirer and a payment processer, allowing both bank and credit/debit card linking for payment processing. Paypal also benefits more from transactions from user bank accounts, which are higher margin, and hence has a huge incentive to promote these transactions over credit-card payments, which also reduces the inter-change fees for merchants. But Visa and MC still have a lot of leverage over Paypal currently, since a majority of its transactions are through these processors.

Other mobile payment services like Apple Pay, Google wallet currently serve as complementary services that use CC/DC to complete the transactions, enabling more transactions through the Visa network. But in the long run, these providers could also expand into using bank accounts that bypass Visa’s payment infrastructure. It seems like virtual and crypto-currencies also pose a threat to Visa, but until fraud and security, which are some of Visa’s core value propositions, have been resolved in processing these currencies (highlighted by the multiple failures in the Bitcoin ecosystem), the current payment networks will not be dislodged.

Sources:

- http://www.nasdaq.com/article/the-toll-booth-businesses-of-visa-and-mastercard-cm403663

- http://seekingalpha.com/article/3193266-visa-market-power-stable-growth-and-high-profitability-doesnt-come-cheap

- http://www.nilsonreport.com/publication_chart_and_graphs_archive.php?1=1

- http://seekingalpha.com/article/3103316-visa-overvalued-in-the-short-term-fantastic-investment-in-the-long-term

- https://usa.visa.com/run-your-business/accept-visa-payments.html/benefits-of-accepting-visa.jsp

- http://www.mastercardadvisors.com/cashlessjourney/

- http://seekingalpha.com/article/2661835-there-is-no-chance-apple-pay-will-disrupt-the-payments-ecosystem

- http://bmimatters.com/2012/03/19/understanding-visa-business-model/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Visa_Inc.

- http://letstalkpayments.com/visa-mastercard-face-increasing-threat-local-networks-crypto-currencies/

- http://seekingalpha.com/article/2181913-the-contenders-to-visas-payment-crown

I hadn’t thought of this industry as displaying network effects, probably because they are more indirect as you mentioned. It’s a good point and made me think about AMEX and their relationship with network effects. AMEX has chosen to go with a business model that relies on swipe fees, while Visa and MasterCard rely on interest charges. Therefore, AMEX charges merchants a higher percentage to accept their card and some retailers would rather not lose that extra 1%, so they don’t accept AMEX. Credit card owners know about this and some would rather not risk being turned down, so AMEX has to draw in customers by other perks such as high membership fees in exchange for high-end perks like access to airline lounges and no international fees. Basically, AMEX goes after the big spenders and retailers that cater to them. Using this strategy, AMEX has been able to overcome the barriers of network effects put in place by incumbents.