The Paper of Record Adapts to a Paperless World

Amidst a digital transformation, The New York Times recognizes data’s value in a digital-first world.

Before Harvard, I spent several years at The New York Times. In the face of collapsing advertising revenues and declining newsprint circulation, The Times has spent years searching for a scalable and repeatable business model (a colleague suggested that this makes it a 165-year-old startup). As the firm’s digital model has evolved, management has recognized the value that data—a source for reporting, and a user experience and operational driver—creates in the digital-first world.

Note: I worked in the NYT Data Science & Engineering group, but this post is sourced strictly from public sources (all linked) unless noted.

Creating Value in Journalism

For years, The Times has leveraged quantitative data and analysis to enhance its reporting. Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight is perhaps the most visible example (now supplanted by The Upshot). Journalists have become accustomed to mining data for reporting insights, even outside of politics. One example: defective Takata airbags. Having manually dug through 2,000+ regulatory “incident reports” to identify accidents related to Takata’s malfeasance, that article’s author handed off her dataset to a data scientist who built a logistic regression model to find those reports among the remaining 31,000 that were also relevant to the article.

Beyond crunching datasets for “traditional” article-writing, Times editors and journalists have also turned to data-driven “automated storytelling.” In sports, their playoff predictor allowed NFL fans to simulate season-ending games to understand teams’ chances of making the playoffs, while the 4th Down Bot examined historical play data to suggest fourth down play-calling. Other pieces tell more typical stories with data augmented with user input (e.g., examine your college’s economic diversity). And in 2013, a popular data-driven dialect quiz quickly became the most-read nytimes.com story of all time. These efforts all represent important efforts to leverage data in pursuit of The Times’s mission to print “all the news that’s fit to print”—even when print matters less and less.

Where The Times thinks I’m from (with remarkable accuracy). After 22 years living in Madison, water fountains will always be bubblers.

Creating Value for the Reader Experience

Beyond crafting news, The Times leverages data to improve reading experiences and surface engaging content to readers. For example: in 2015 the newsroom launched Blossom, a Slack bot that recommends stories for posting on Twitter and Facebook based on past high-performing articles and their text composition. Editors retain final say over news coverage decisions, but they are not averse to improving the reader experience with input from data.

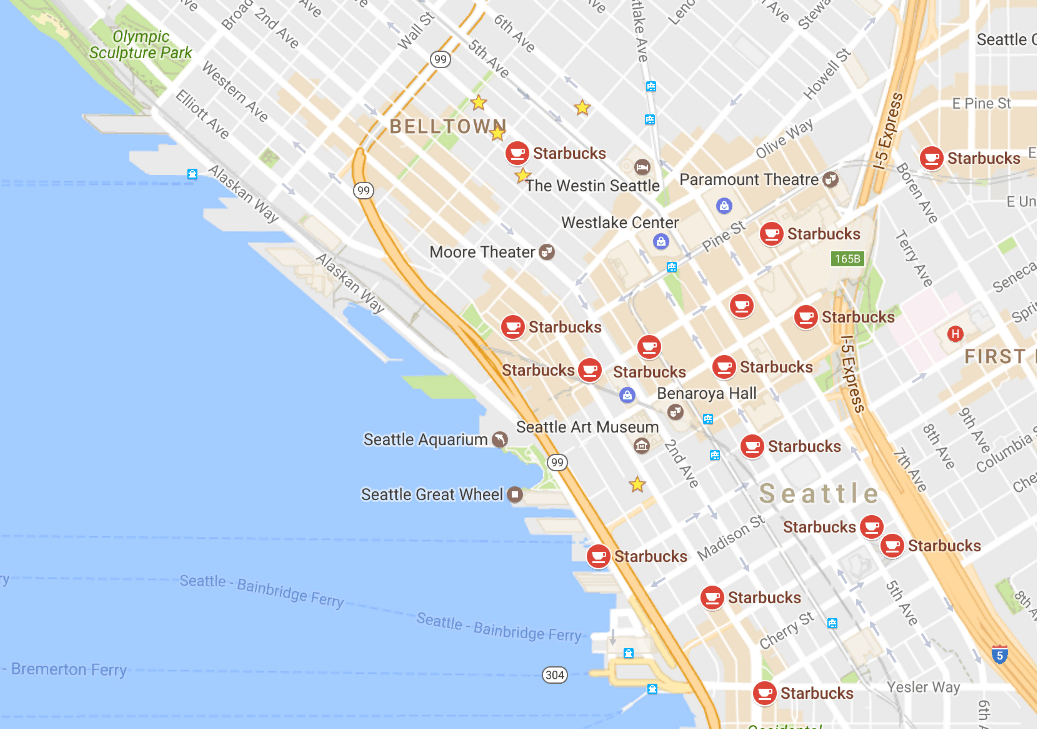

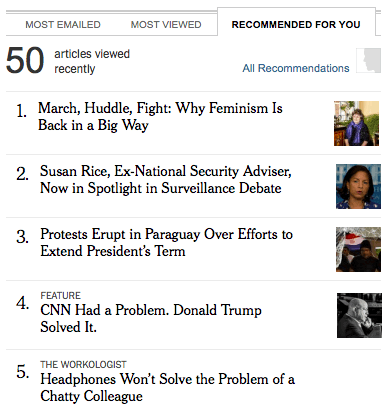

Beyond manually-curated suggestions, The Times also operates an article recommendation engine (shown under the “recommended for you” tab on nytimes.com) that recommends articles based on readers’ browsing histories. As engineers discuss, the system uses a topic modeling algorithm (LDA) to transform an article’s text into a set of features that describe its content, enabling comparisons to other articles. By comparing new articles to past articles that users have read, the engine surfaces engaging content for those readers. Thus, The Times’s data capabilities transcend news-writing, improving the reader experience throughout.

Capturing Value

The Times continues to compete with other news outlets—and companies like Facebook—for attention. To capture value that data-driven journalism and product enhancements (like those above) have created for readers, they clearly hope to realize increases in digital subscriptions. Beyond that, The Times also applies the same granular readership data that underlies article recommendations (as well as other data sources) to problems in marketing and operations. Reader histories contain powerful signals that identify potential subscribers and unsubscribers and reveal international value capture opportunities. And to avoid waste in The Times’s “dead tree” business, data scientists have used newspaper sales data to match newspaper printing to expected demand.

Of course, on all of these fronts The Times isn’t the only game in town. FiveThirtyEight (under ESPN ownership) remains committed to data-driven journalism, and appears to have an edge in election predictions (shortcomings aside). The Jeff Bezos-owned Washington Post has also beefed up its data and algorithmic expertise, using data to optimize headlines (with multi-armed bandits) and leaning on algorithms to write short news stories. Both players—and plenty of others—will be worth watching as the digital media landscape evolves.

Where We Came From; Where We’re Going

Building these analytic capabilities necessitated significant investments in technical infrastructure and knowhow. My tenure overlapped with major engineering advancements in the logging technology required to gather the granular user data that powers efforts described above. And in early 2014, a private Times Innovation Report leaked to the press, wherein company executives identified the challenge—and progress made—in hiring data- and tech-savvy newsroom staff.

But perhaps the biggest challenge to adapting to the “Big Data” age is cultural. The Times has traditionally enforced rigid separation between journalistic and business staff in both the built environment (housing the newsroom in a distinct physical space) and in the org chart (an arrangement known colloquially as “The Wall” or “the separation of church and state”). As recent progeny of the Innovation Report indicate, The Times has built better products by carefully softening these barriers, building bridges between business-focused analytics staff and the newsroom while eschewing conflicts of interest.

In all, this is clearly an interesting time for the Times. Management has invested heavily in analytics capabilities with the aim of improving the firm’s products. Still, despite incredible progress, digital operations remain $300 million short of their 2020 revenue goal. Time will tell if data will be the difference-maker in The Times’s business model search.

Great post, Micah. I took the dialect quiz again and confirmed that I am indeed from Texas. I’ve got about thirty questions I want to ask you but will try to limit myself to a few. Did you feel like the Times’ push into analytics yielded results during your time there? Is it inevitable that the barrier between the business and the journalistic staff will be totally disassembled? My very cursory, likely naive, and sadly pessimistic guess is “probably,” so the business can survive against free content and the tech giants. Is there any concern users could get caught in a content loop or a quasi-echo chamber with the recommendation engine?

Thanks, James! Your results question is a good one. I spent a lot of time there building foundational infrastructure and wish I could have stuck around to see more of the benefits that resulted from it, though I’m optimistic that data has paid dividends in some subscriber retention and operational challenges. But the end results of news applications are harder to assess. Quality reporting is expensive, and absent a lucrative advertising business model it is difficult to say how much data-driven reporting drives subscriptions. My feeling is that The Times’s relative success in attracting digital subscriber revenue is partially driven by its data efforts, but I cannot disentangle that effect from others.

As for the barrier between news and business, I would expect it to always exist in some way. As long as the Times has an advertising business, I would expect strong cultural resistance to full dissolution. And advertising aside, I think that fully breaking down that barrier would require reorganizing the company and putting news operations under the control of someone on the business side. I don’t expect that to ever happen, so I would expect that the company simply continues to drill small holes in the wall and develop working relationships with particular business groups (while excluding others).

Your point about the recommendation engine is a great observation. After all, that’s a severe criticism of Facebook’s role in the news landscape—that it has turned confirmation bias into an incredibly lucrative business model. I think the fact that editors continue to oversee Times coverage and that the firm doesn’t rely on algorithmic curation lessens risks associated with the recommendation engine. Of course, the fact that people self-select into reading Times content and/or discover it as a result of echo chambers on social media remains a problem.

Great post – thank you for sharing! Also thank you so much for sharing your machine learning deck – it is awesome.

I think the cultural aspects of implementing data are very interesting. A large problem is that data models are iterative, thus might not work as well at first, hurting their credibility amongst skeptics when first launched. Also, I think it is really hard to launch a data product that is “augmenting” what employees are doing. As the guest professor said in class, why have a model if people are still able to override it whenever they want? I think this is a fine line to manage, and the tension will make adoption of data tools slower than it should be.

Thanks, and glad you enjoyed the slides! Loved your observations about cultural challenges of adopting data-driven management. One way of approaching data-driven change that I have seen be successful in the past is to find particular leverage points or “champions” within the company that who most willing to try new approaches, and pursue open-ended projects that generate new questions that they want answered. At The Times I actually found that the executives who oversaw the “old-fashioned” printed newspaper business were incredibly enthusiastic about applying data to their work, and were really happy to finally have better data that they could use to optimize their work.