The League: Challenges of Scaling an Exclusive App

How can The League grow its user base while all the while maintaining its brand as an exclusive place to find like-minded people to date?

The League is a digital dating platform that connects users looking to meet other people similar to themselves.

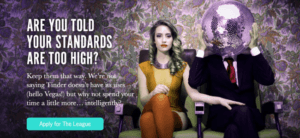

It began by having its founder Amanda Bradford reach out to many of her friends from business school and ask them to create profiles for the new platform. The pitch of the platform would be that it was for people with similar educational and professional backgrounds and would allow them to connect in a more targeted way versus an application like Tinder in which people suffered from “swiping fatigue” and it was more difficult to find like-minded people to date. The matching algorithm would present up to three profiles from which to choose each day, and if there was mutual interest, the platform would allow them to connect and begin chatting.

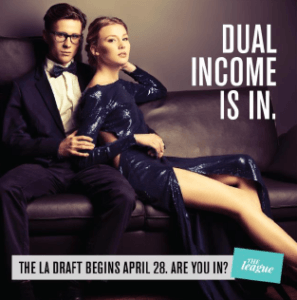

As The League has tried to scale, it has faced challenges in extracting value from its customers. It operates a freemium business model, as it allows users to access the platform (once approved) but then offers a premium experience with more profile matches and other benefits for those willing to pay $200 per year. Therefore, to grow revenues The League has to find more users who want to use the service, and then The League needs to convert them from free users to paid. It has to do this while all the while maintaining its brand image of being an exclusive platform on which to meet people.

In addition to some forms of traditional advertising (like billboards and posters on bus stations when it launched in San Francisco), The League has relied on local networks effects to expand its user base. The more they can acquire users and convince them that they are the best platform to find potential mates with similar educational and professional backgrounds, the more others will want to become part of this community. The greater number of high quality users, the more new users will be willing to pay for the service.

Global network effects are limited, however. Because its users look for dates locally, the presence of The League in a new city creates very few benefits for its existing user base. The League has expanded to 30 other cities in the United States and in Europe, yet there is a question of when they will have hit most major cities and, after that, how they will continue to grow.

Furthermore, multi-homing does continue to occur. Though it brands itself as “Tinder for Elites,” many of its users continue to use Tinder as well as other dating applications. There are no switching costs between going back and forth between these platforms. The League therefore continues to work on convincing its users that its service is worth paying for.

Going forward The League must figure out a way to grow its user base, convert more of those users into paying customers, and do so all the while maintaining its brand equity as an exclusive place for like-minded people to find potential mates. As it expands it risks becoming too similar to apps it tries to differentiate itself from, like Tinder. This would also allow a new platform to come in and do the job that The League initially started trying to do. Unless it is able to resolve that tension, I would be pessimistic about its future longevity.

The League is an interesting entrant into the dating app space. I absolutely agree with your points that it strikes a delicate balance — on one hand, branding itself as more exclusive and carefully curated than Tinder, but on the other, it can’t be so elitist that it misses out on tapping into network effects. Dating apps are tricky because their incentives are at odds with those of the user — a successful match means users no longer need the app, whereas the apps want to keep as many active users as possible. In terms of the newer entrants, Bumble actually addresses a pain point (starting and maintaining conversations) and differentiates itself the best, whereas The League is not so differentiated from The Hinge or Tinder. Perhaps The League can also offer recommendations on local date spots (and even offer a concierge service to access exclusive spots) to encourage stickiness and to better differentiate itself, while sticking to its exclusive brand.

Interesting point to consider – how do you scale an “exclusive” product? Perhaps this is a case where you would rather have a smaller base of high paying customers, and therefore freemium doesn’t make sense as a model. I also agree with JZ that The League should consider diversifying its revenues through things like events if it has any hope of surviving or becoming profitable.

Very interesting, Ari! A couple of thoughts came to mind as I read your post. The scaling concern is an interesting one. Dating apps are somewhat unusual in that disintermediation is particularly likely to occur – many users are looking to meet someone through the platform but will then continue that relationship outside of the platform. If the app is successfully connecting those whom are most “like-minded,” those individuals may be expected to meet that special someone more quickly and, therefore, leave the app. That will always be a challenge for growing the userbase. There is also extremely high multi-homing. Many who use dating apps have multiple on their phone that they’re using at any given time. There’s no doubt that The League is operating in a highly competitive space. It’ll be interesting to see if their differentiators – exclusivity, “elite” clientele – will be enough for it to win or if they will instead become a hinderance.

Thank you very much for the post. I did not realize that the league uses a yearly subscription at an extremely high price point. I think the fact that the company goal to differentiate itself through exclusivity limits its’ user base potential. As a result, to be profitable, it needed to charge a very high price point. This is a good thing for an alignment in branding. However, it is difficult to see them grow the premium users. There are so many competing dating apps with a significantly lower price point. I believe the best way is for them to compete directly with high-end offline dating services. The $200 per annum should not be an issue in that market. The question is how big is that market and how would the league increase its service offering to compete in that market.

We had a case about this company in Strategy & Technology class last semester. I found it very interesting idea that fills that tries to address a market demand. However, it never addresses the complex physiological barriers of love and relationships in this elitist filtering model. I think the main issues nobody wants to accept that they are looking for only resume type features in relationships. Such a materialistic view would not be appreciated by both sides in a very obvious way.

Rachel brings up a great question—how to scale “exclusive” products. Network effects can be positive and negative—while some users being added on to a platform can be additive to the experience, others could dilute the exclusive brand experience. Just as with luxury fashion, where scarcity can be a driver of value, The League must flirt with that delicate balance. Other platforms parcel out profiles a few at a time to keep users from seeing the whole set of possibilities at once, which could keep an air of exclusivity, but ultimately, the company has indicated a cutoff for membership and will ultimately push against that core brand proposition as it seeks to expand its market.

Very interesting post, and certainly highlights a difficult problem that many of these dating apps are facing: how to differentiate itself in a highly competitive, multi-homing-type environment. The lack of physical interaction on the app often encourages people to make very swift judgement from short descriptors and profile pictures. While our generation has certainly become more comfortable with digital dating platforms, I think it’s important to bring in elements of face-to-face interaction as a major source of differentiation. The League could potentially organize social events for selected individuals on the platform based on common interests and backgrounds, and this will allow people to interact with multiple people in a comfortable environment. These events could be “invite only”, which would offer a sense of exclusivity, and the League could find these social events as an additional way to monetize the platform. Another reason why social events are important is that this will help build a sense of community, as users will see others as people with multiple dimensions and interests rather than profile pages. Having these unique experiences for users would also help strengthen its platform and stickiness.

In addition to the problems discussed by other commenters, I wonder if The League will run into issues by maxing out it’s total addressable market. Given that the platform succeeds by eliminating users (couples match up and stay together) and there are only so many users that fit into this “exclusive” community, I worry that scaling will be difficult, if not possible, forcing The League to be a niche player for its existence. As a niche player, they will be highly susceptible to competitors willing to take a lower margin. The offering could become essentially commoditized.

Very interesting post! I echo some of the other ideas voiced in comments above and definitely think it could be a good idea to try to organize events and find other ways to connect users with similar interests. Perhaps The League could try to attract more paying users by deploying a program similar to that of Match.com, offering to pay back some portion of the membership fee if a match is not made within a given time frame.