The “Harvard” of Dating Apps: The League

Is The League doing enough to sustain its global network? Does The League truly want us to find love? Or instead does it hope that we continue swiping left so that we stay on the platform and continue to grow their bottom line?

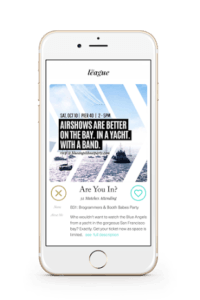

With a reputation of being known as the “Ivy League” of dating apps, The League, founded by Amanda Bradford, is a dating app targeted towards young, working professionals. With the core goal of the service to be to help singles meet each other and ultimately date, The League restricts its pool of singles to those that are “ambitious young professionals”. The main question that comes into everyone’s mind is, how on earth does The League determine whether or not someone is an “ambitious young professional”? Unlike its main dating app competitors, Hinge and Tinder, The League relies heavily on LinkedIn data moreso than Facebook data to investigate its aspiring members. Once a user downloads the app, they are prompted to join a waitlist (which in some cities can be 20-30,000 users long) before being able to officially use the service. The League has an acceptance algorithm that then scans social networks (LinkedIn and Facebook) to ensure applicants are in the right age group and are career oriented. Once accepted, users can then browse through a handful of matches that are offered to the user. New batches of matches are supplied to users during “happy hour” every day at 5pm. The app uses an algorithm to ensure that users aren’t shown current coworkers or people within their primary network to avoid awkward encounters.

Value Creation: The League is a multi-sided platform, connecting consumers interested in dating with each other and advertisers with a source of young professional consumers. The app creates value by providing an exclusive platform for users to browse and learn about the variety of single individuals in their respective location and to connect with these individuals via a chat function on the app (if both users have already indicated that they are interested in each other) and ultimately in an in-person date off of the app.

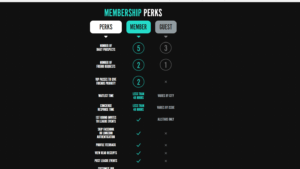

Value Capture: The League operates as a freemium model. Users can choose to become League Members and pay a monthly membership fee in exchange for an increased number of daily prospects, friend request capability, receipt of VIP passes to give friends priority, and other perks such as read receipt functionality, profile feedback, and first round invitations to League social events. Furthermore, The League captures value through click through advertising revenues. The greater the Company’s network, the more appealing it is for advertisers to advertise on the platform.

Source: The League , Company Website

Key Challenges: The primary challenge dating platforms face as a business model is that the inherent goal of the service is for users to ultimately disintermediate and date each other. This ultimately results in users exchanging phone numbers, and moving off of the platform. If users are “lucky”, they will find a serious relationship relatively quickly and have no further use for the platform at all. The better The League is at doing its intended goal, the worse off it becomes because it loses members from its network and suffers from loss of advertising revenue (another primary source of revenue aside from premium membership fees). In addition, there is a great deal of multi-homing in the mobile dating industry. Given low switching costs and limited differentiation between platforms and services, many consumers have free accounts on several mobile dating platforms. There is minimal brand loyalty in the mobile dating space.

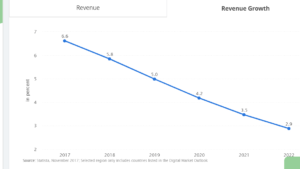

The League’s Response: The League attempted to mitigate the risk of multi-homing by incorporating the waitlist feature to its service. By giving users the impression of exclusivity and elitism, The League hopes to differentiate itself from other dating apps that target more “mainstream” customers. In addition, The League worked to mitigate the risk of a reduction in global network post dating match by incorporating in-person dating social events into its platform. Rather than just offering a dating matching service, The League aims to create an entire experience around dating. It offers domestic and international trips, social events such as concerts, and even athletic events for couples and singles to enjoy each other’s company based on shared interests off of the platform. By creating social experiences such as these, The League is working to retain its global network even after it has accomplished its goal of matching individuals as couples. While the online dating industry is valued at about $2.2bn, and there are over 50m Americans looking for love online, revenue growth for the industry is projected to slow through 2022.

While the online dating industry is valued at about $2.2bn, and there are over 50m Americans looking for love online, revenue growth for the industry is projected to slow through 2022.

Source: Statista, November 2017

Is The League doing enough to sustain its global network? Does The League truly want us to find love? Or instead does it hope that we continue swiping left so that we stay on the platform and continue to grow their bottom line?

Sources:

http://www.businessinsider.com/the-league-raises-21-million-2015-1

http://www.businessinsider.com/the-league-launches-in-la-tries-to-monetize-2016-4

http://www.theleague.com/membership/

http://academic.mintel.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/display/822235/

https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/434414/Reports/Index_Reports/Liftoff-Mobile-Dating-Apps-Report.pdf

Very interesting. It strikes me a strange that an app for which network effects are so crucial (thinking of the engagement and size of user bases of tinder, bumble, etc.) would be “exclusive.” Wouldn’t that necessarily hurt the goal of reaching critical mass to achieve frequent, yet quality matches? I also wonder if each app attracts a particular usage profile. Tinder, for instance, has the reputation of being a hook up app. Does that result in a different “seeker” profile vs. others like hinge?

I find the conflict inherent in the business model fascinating. As you said, the better The League is at its intended purpose, the worse off the platform is. I believe that the exclusivity might serve as a type of competitive advantage.. users who are accepted likely feel special and important. I would be curious to know how network effects work in a market such as this. For example, is a person who found love on the platform more likely to refer friends than someone who didn’t? Do consumers have any understanding of various matching statistics across different platforms? I think that online dating will remain prevalent in the future, but I also wonder if The League is doing enough to differentiate itself from a growing number of apps.

Thanks for sharing the post. I had never thought about the intrinsic flaw in the League’s business model. The better the League is at the job-to-be-done (helping people find relationships), the less valuable its platform becomes. The company essentially has to constantly refill its marketing funnel in order to replace the users that leave the platform. To that end, demographic trends and consumer preferences are highly important in understanding the long-term sustainability of the company’s business model. The company must ensure that it attracts younger generations to the platform in order to refill the funnel. And it must ensure that the League stays relevant in a competitive space.

Great post! Beyond the conflict of business model of a dating app mentioned in the comments above, I would also love to learn how does the premium fee work for this business. Given highly competitive space, lack of loyalty and high multi-homing, are there actually people willing to pay for it? Maybe, The League could differentiate by offering exclusive services for free to make people come back on it again and again? Or are there truly exclusive feature that can help it stand out without getting a “niche app” tag?

Interesting!! I find the niche market they chose to focus on, (high flying achievers), an interesting choice in terms of willingness to pay. Is there any data on a higher WTP from this segment? Or a higher conversion from the freemium model to the paid one? I would guess that was the founders hypothesis, but curious to see if data backs this up.

A little late to the party, but great post! I wonder about ways that The League can reduce disintermediation. How effective is their messaging platform? Is it good enough to be an alternative to text messaging? Is it possible to make one’s phone number available to the other party at a certain time, and even call them through the app – similar to WhatsApp? A notable weakness of GroupMe is the inability to call through the app, and that tends to cause disintermediation. I wonder if The League could mitigate this risk through better integration.

From a BSSE standpoint, the league seems to have crafted some sort of new market disruption, with arguably more valuable users, despite the disintermediation issue. My thesis is as follows : disintermediation is bound to happen, so the focus should be on maximising user LTV; while premium accounts do help, the bulk of revenues must come from ads. The strength of a “niche market” like the one the league is addressing is that you can safely assume there are no “fake” profiles. Other apps have to deal with bots or spam accounts, hard to track / identify by the platform itself. On the League, users are being vetted — hence ads can be sold as higher quality and conversion rates are likely increased since profiles would be more complete and show more data points.

It’s an interesting model that they chose to go with. While targeting a niche market bears with it some limitations, the aspirational aspect of it coupled with the exclusivity might end up drawing more users and attention. It’s interesting to see how a curated platform like this will grow over time.

I don’t have much to add to the discussion so far. My questions revolve around their current business model and if they can sustain on fees from premium profiles alone. Are there any in-app ads or do they capture any value from the events and activities they facilitate? Thanks for sharing!

I wonder if one way to combat The League’s intrinsic business model flaws is to make the platform appealing to people seeking to meet others in general, regardless of their relationship status. While I’m not sure what the financials look like for platform companies like MeetUp that offer members the opportunity to meet and engage in activities with other like-minded individuals (e.g., people who like the outdoors, people who like cooking), such a model could serve as a way to retain users, even after they find “the one”.

I’m not sure the waitlist feature mitigates multi-homing. If anything, it might increase it. If I am recently single and have to wait X weeks to gain access to an app, I am likely to download and use other apps in the meantime. Furthermore, I think showing a limited number of individuals might contribute to multi-homing. “Swiping” is somewhat addictive, and even though The League might provide more quality matches, users may feel the need to continue playing the “game” of swiping.