This post was originally published in the HBS Alumni Bulletin.

It’s a sunny May afternoon in LA. Søren Bjerg, a slender and pale 21-year-old with chunky glasses and a black hoodie, is sitting in the den of the house he shares with a half dozen other guys. It’s decorated the way you might expect it to be: lots of technology and energy drinks and not much else. Bjerg is staring blankly at his computer screen. He adjusts his two monitors and fiddles with the speakers as he awaits the start of his next League of Legends battle. As he does many days, Bjerg will sit here playing the popular video game for the next eight hours.

As the game begins, Bjerg guides a blue-haired magician named LeBlanc across the Fields of Justice, hurling spells at the enemy’s minions. He narrates the chaotic game, often profanely, as he and his four teammates confront their opponents, another team of gamers. Each is trying to reach the other’s “nexus.” A half an hour later, Bjerg’s team suffers total defeat when their glowing blue nexus is shattered.

“OK, now I’m going to read out some subs and resubs,” he says, without missing a beat. Each of the nonsensical screen names he reads is that of a viewer who has been watching him play. Bjerg is a professional gamer from Denmark known as Bjergsen. Several thousand people are watching him play LoL, as the game is known, right now on the streaming service Twitch, and tens of thousands more will watch the video of the game later.

To guarantee that Bjerg, a longtime fan favorite on Team SoloMid, reads your name and maybe your message aloud, you need to “sub,” or subscribe. In the 90 seconds before his next game starts, Bjerg announces the names of some 30 subscribers, each of whom just pledged $4.99 to $24.99 a month to support the player. Meanwhile, ads for Red Bull and Geico appear at the bottom of the screen, and a link on the right offers Team SoloMid gear. A constant stream of fan comments races alongside the game, and on archived videos, flashy Budweiser ads periodically interrupt the action.

Each month, Twitch says, more than 100 million people will log in to watch an estimated 23 billion minutes of professional esports players and amateur gamers streaming video game play. By year’s end, market analyst Newzoo forecasts, the online global esports audience will reach 385 million people with revenues of nearly $700 million.

But if all this seems a little crazy to you, you aren’t alone. As Jeffrey Glass (MBA 1994), a serial entrepreneur and co-owner of an esports team, explains, “Esports is the most gigantic industry that nobody’s ever heard of.”

To understand esports, the first thing you need to know is that competitive video gaming has been around a lot longer than you think.

On November 10, 1980, five teenage boys faced off at the Warner Communications headquarters in Rockefeller Center in the middle of New York City. They had traveled with their families from around the country to vie for the title of Space Invaders national champion. Thousands had played the video game, released that year in the United States by Warner brand Atari, in regional tournaments in the months leading up to the November event. Now, a small crowd of family, friends, and reporters watched quietly as the finalists defended earth from pixelated aliens on their television screens.

“‘Fweep, fweep, fweep,’ went the lasers. ’Krch, krch, krch,’ went the doomed invaders,” the Associated Press reported from one of the world’s first live esports events. The AP was not enthusiastic about the prospects of video game competition as a spectator sport—“for two mind-numbing hours, contestants stared at their screens and manipulated laser guns”—but Warner Communications was elated by all the attention it received, and the contestants understood its cultural impact. “I hear I’m kind of a hero or something in school today,” the third-place finisher boasted to his hometown paper.

That was the dynamic that would define competitive video gaming for nearly two decades, even as technology changed the pace and complexity of the games and allowed for easier player-fan interaction—enthusiastic gamers, a largely oblivious and skeptical public, and occasionally supportive video game publishers who saw marketing opportunities, but didn’t dream bigger.

It wasn’t until the 1998 release of StarCraft, a game of warring alien factions with a strategic complexity often likened to chess, that the subculture of competitive gaming and its economic potential came fully into view—first in South Korea. The country’s well-developed internet infrastructure had birthed a vibrant gaming community, and with support from the government and South Korea’s largest corporations, esports quickly went mainstream in the early 2000s. Leagues were organized by a central authority, and competitions were televised. Long before the rest of the world discovered the 21st-century sport, South Korean video gamers were held in the same regard as soccer stars.

It was more than a decade before video gamers in the United States became a big part of the phenomenon. Twitch, which launched in 2011 as the YouTube of gaming, was designed for watching and streaming video game play and connecting with like-minded players. It was also the perfect vehicle for broadcasting esports; just three years later, Twitch was acquired by Amazon for nearly $1 billion. The acquisition was viewed with amazement by those unfamiliar with the young and rapidly growing sector. But a year later esports achieved a milestone traditional US sports fans could understand.

Thirty-five years after the Space Invaders tournament at Rockefeller Center, on August 22, 2015, the house lights dimmed at Madison Square Garden, a few blocks away. Music pulsed and multicolored strobes illuminated cheering audience members, many waving signs emblazoned with their team’s name. The screaming, sold-out crowd at one of the country’s most storied sporting venues was counting down to the appearance of Søren Bjerg and Team SoloMid who would challenge their rivals, Counter Logic Gaming, in the League of Legends regional championship.

“That event put the esports industry on the map in the United States,” says Dan Fleeter (MBA 2010), vice president of corporate development and strategy at the Madison Square Garden Company, which now hosts esports events in its venues across the country. “But, to use a basketball analogy, esports is still in the beginning of the first quarter, in terms of reaching its potential.”

Almost everyone relies on traditional sports analogies when discussing esports.

“Esports,” like the term “sports,” refers to the entire universe of competitive gaming; the individual sports under that umbrella are the video game titles. League of Legends, Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (a first-person shooter game), and Dota 2 (a team-based battlefield game) jostle for dominance—the baseball, basketball, and football of American esports. Hearthstone, a one-on-one card game with fantasy elements, is the up-and-comer. Think soccer in the United States.

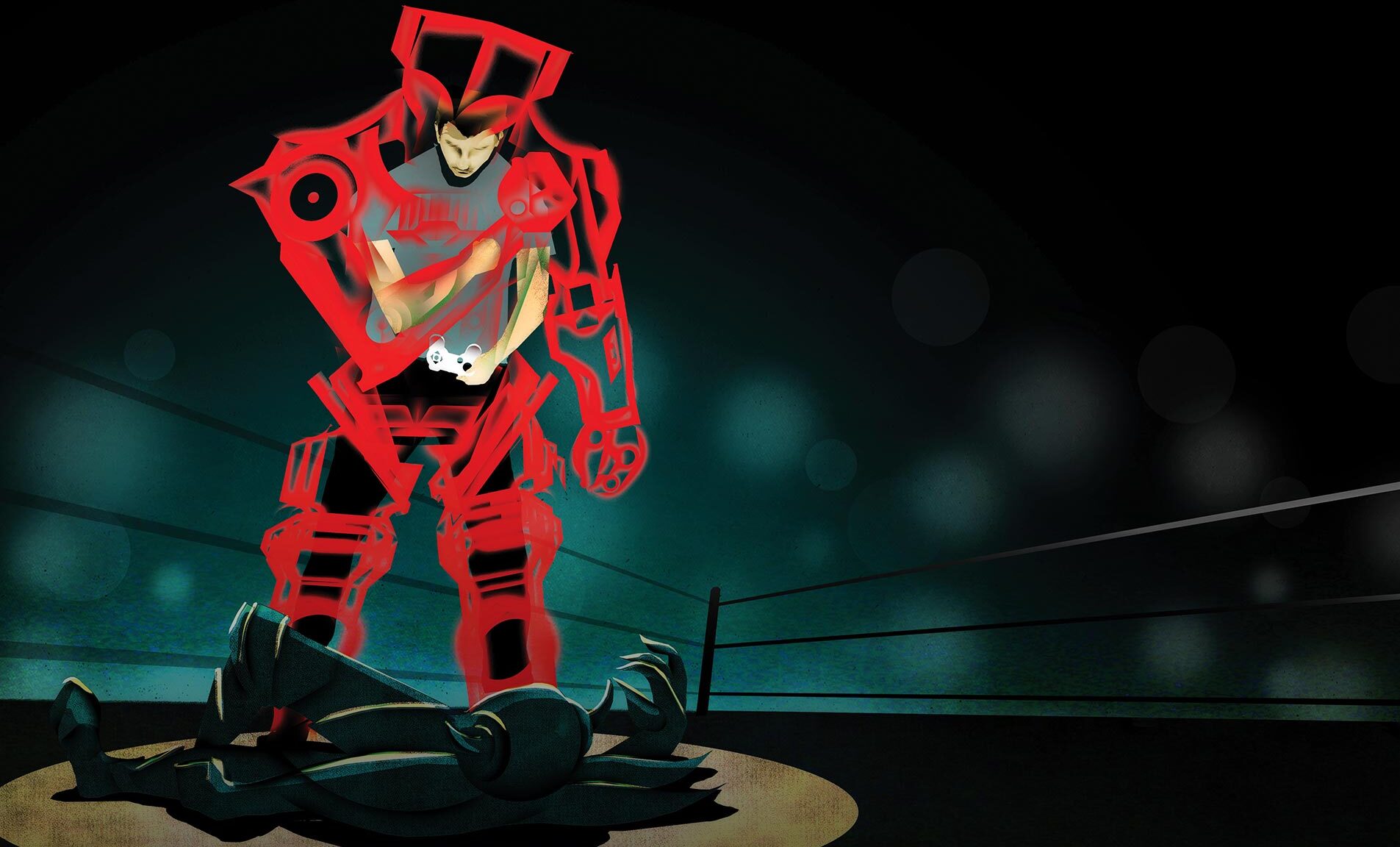

The video gamers are esports’ celebrated athletes, often living together in team houses with coaches and intense training schedules that exercise fast-twitch muscles in the fingers and hone game strategy skills. As in any sport, injuries are a risk—carpal tunnel but also deep vein thrombosis from hours of sitting—and youth is a virtue. Many top players, almost all of whom are men, are still in their teens, and most retire by their mid-20s, when those fast-twitch reflexes begin to slow.

The practice games that stream live on the internet are akin to spring training baseball games; the games that amateur players broadcast are more like a pickup basketball game. The world championships in each of the major games are the Super Bowl.

But the comparisons begin to fall apart when attention turns to business considerations.

“The NFL owns the NFL; the NFL does not own football,” says HBS professor Youngme Moon, underlining one of the biggest differences between the business of sports and the business of esports. That means video game publishers can each dictate how a competitive league is developed around their game; there can be no competing organization without a publisher’s blessing. Some, such as League of Legends publisher Riot Games, serve as commissioners of their own leagues—to return to traditional sports analogies—while others outsource the responsibility to a third party. That new ownership model, along with esports’ reliance on streaming, not television distribution, and the global popularity of teams that aren’t tied to a specific geography, requires a whole new business model.

As co-head of esports at Riot Games, Jarred Kennedy (MBA 2004) is one of the people charged with building an entirely new professional sport. It’s a challenge that baseball and football first faced in the late 1800s; more contemporary models are extreme sports and professional poker, but neither was digital-first the way esports is. You can’t take anything for granted in this new world, Kennedy says. “You’ve got to establish how you want to operate. Then you have to figure out how do you build a business model. Are media rights going to be the way we monetize? What role do ticket sales have? How do we think about where we host events? How do we think about how to foster talent?”

There’s a lot at stake for publishers as they answer each of those questions. The sector may not yet be bigger than basketball—breathless headlines to the contrary often compare global, cross-platform viewership for esports championships with basketball’s US television ratings—but it is expected to more than double in size, to nearly $1.5 billion, by 2020. And those in traditional sports are taking notice: Robert Kraft (MBA 1965), owner of the New England Patriots football team, recently announced an investment in a new esports team that will compete in the first-person shooter game Overwatch.

“What we’re seeing is the birth of what will eventually be an extremely lucrative industry,” says Moon, who is an investor in an esports team.

Esports entrepreneurs are asking the same types of questions the publishers are asking: How can we improve the gaming and viewing experience? How can we leverage data to develop marketing opportunities on streaming platforms with millions of broadcasters? And how can we grow the fan base from its mostly male, largely millennial roots? Each answer has the potential to reshape the way technology, players, advertisers, and fans interact in this new ecosystem—and the long-term viability of the sector.

Tiffany Norwood (MBA 1994) is reconsidering the whole gaming experience as cofounder of Emortal Sports. The fledgling video game publisher is developing several virtual reality titles—Paradox Rift, a first-person shooter game, and Beasts and Heroes, a battlefield strategy game—and a technology platform that Norwood hopes will unite the fragmented gaming world. On that platform, she says, players would navigate every game using the same avatar, an innovation that would change game strategy. For Norwood, having a single gaming identity would create a stronger connection between gamers and fans and introduce an element of reality into the digital world. “This would be a true virtual athlete that can get injured,” she explains. “You would have to think more like a real athlete when you are playing.”

Leveraging the connection between players and fans is at the heart of the marketing platform Endorse.gg, created by Brandon Freiberg (MBA 2018) and Joe Kiernan (MBA 2017) and based at the Harvard i-lab. Endorse.gg (“gg” is esports slang for “good game”) recruits esports “influencers” to represent brands to their audiences during streaming sessions. The data available on viewers and the high level of engagement is attractive to advertisers, both those you might expect, such as NASCAR, and some that are more surprising, such as Sallie Mae. And slowly, larger advertisers like Coca-Cola have entered the market. “I still have to explain what esports is sometimes, but then I tell them about audience size and their purchasing power,” says Freiberg.

And Gamer Sensei, founded by William Collis and Rohan Gopaldas (both MBA 2011), is designed to train the next generation of esports professionals and the amateur gamers who make up the majority of the esports audience. The website matches players with personalized coaching in a variety of games, catering both to the serious players and to the clueless parents who want to better understand their children’s interests. “This is something I wish I could have shared with my father,” says Collis, an avid gamer.

Collis, like many of those who are involved in the early days of esports, approaches the industry with an eye toward the future. He is an optimist; they could be building the next national pastime. “Everybody has a memory of going out and throwing a baseball with their father,” he says. “Esports is the experience I am going to share with my child.”