This post was originally published as part of HBS’ Cold Call Podcast.

As a vast place full of limitless possibility, space is a huge draw for brilliant minds and big ambitions.

A new generation of billionaire entrepreneurs is vying to lay claim to it. Be it Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, Richard Branson, or Paul Allen, some of the world’s wealthiest and most ambitious businesspersons are going to great lengths and great personal expense to put their stamp on commercial space travel and the so-called New Space sector, turning a very cold place into a hotbed of startup activity.

Professor Matt Weinzierl has taken careful note of this trend and has his own goals for the New Space sector: namely, to use it as a means of launching classroom discussion and research on the subtleties and challenges of the relationship between the public and private sectors. An associate professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, Weinzierl is the author of a case entitled “Blue Origin, NASA, and New Space”, which he uses as part of his course in the MBA elective curriculum, “The Role of Government in Market Economies”. In that course, Weinzierl and his students investigate when and how government can work with markets to help society achieve its goals. In the rapidly-evolving space sector, he argues, society will have the opportunity to determine the proper roles for government and the private sector nearly from scratch.

“The idea of leveraging the private sector and its efficiencies to help achieve public sector goals is a powerful idea for the students to engage with,” Weinzierl says. “It helps that we’re at a remarkable point in history where we have people like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk with the vision and the capital to even make such a discussion possible.”

Blue Origin and CCDev

The Blue Origin case focuses on the aerospace engineering company Jeff Bezos began in 2000, just six years after founding Amazon. As his success with Amazon grew, Bezos was able to aim Blue Origin at the lofty target of commercial space travel, where he hoped to change the New Space sector as dramatically as Amazon was changing retail. His timing was characteristically prescient, since NASA was in the process of winding down its space shuttle program and gearing up for its Commercial Crew Development program (CCDev), where it would partner with private New Space companies to share the cost burden of near-Earth activities like supplying the International Space Station.

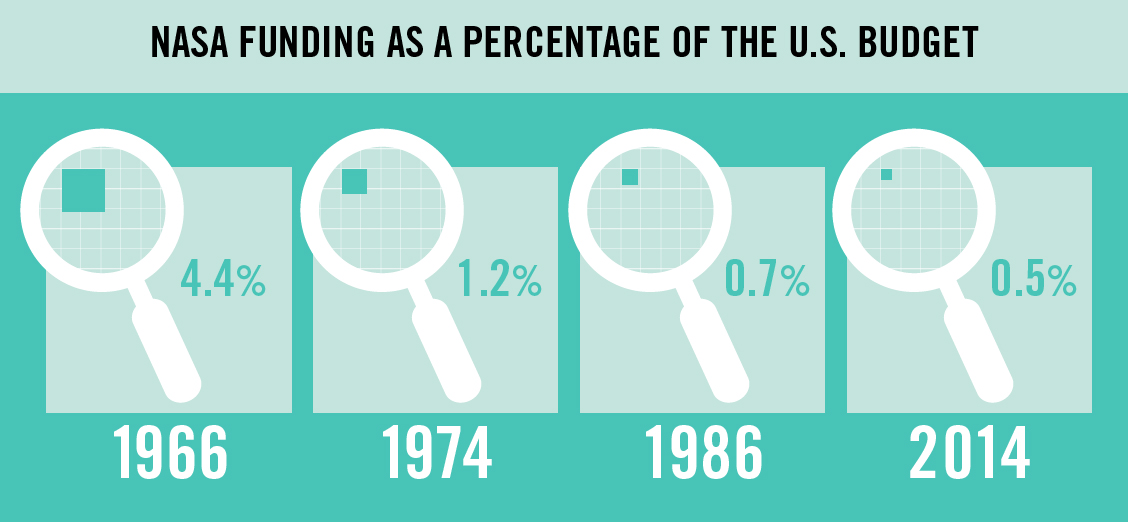

NASA has always had private sector partners. But its early success with the Apollo missions of the 1960’s had been followed by decades of decreased funding, which the case notes peaked at 4.4 percent of the U.S. federal budget in 1966 and had shrunk to just 0.5 percent by 2014. To fulfill its vision for the exploration and study of space, NASA needed to find a way to do more with less. Its solution was to offload some of the costs and labor of low-orbit efforts so it could once again afford to dream big.

Enter Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin.

“We often think of business as motivated by quarterly earnings and short-term thinking,” Weinzierl says. “And yet in our modern system, there’s a strange inversion because our government is so driven by short-term election cycles and fundraising. It makes doing visionary things very difficult. In some ways, NASA offloading some of the shorter-term development to companies like Blue, and reclaiming it’s longer-term pursuits, is a reversion to what the model is supposed to be when the politics are working.”

Begun in 2009, CCDev has allowed companies like Blue Origin and Elon Musk’s SpaceX to leverage NASA’s funding and expertise in their own rocket and spacecraft development. The multi-phase initiative has shown dramatic success in recent months. Private companies have carried out resupply missions to the International Space Station, and both Blue Origin and SpaceX have safely landed rockets back on Earth after flights into space, a key step toward lowering the cost of access to space and making commercial space travel routine. NASA, meanwhile, has turned its sights on a mission to Mars and innovative technologies for deep space exploration. CCDev offers a clear example of how the public and private sectors can work together to pursue commercial goals and public goods at the same time.

“If a private company can find a way to develop a technology that is profitable for itself and the public sector can piggyback on it, that’s a pretty efficient and sustainable model,” Weinzierl says. “That’s the place where we want to head and Blue Origin is trying to do exactly that.”

The Future of New Space

Weinzierl’s case begins by introducing readers to five-year-old Jeff Bezos, who watched Neil Armstrong take humankind’s first steps on the moon, an experience Bezos said “deeply imprinted” him. It fostered his interest in and admiration for the space sector and the work NASA was doing there, something that later drove Blue Origin’s successful partnership with the agency. Despite that admiration, the case ends at a provocative decision point: Bezos and Blue Origin must decide whether to follow the productive NASA partnership into a third, more complicated phase of CCDev, or strike out on their own in the name of efficiency and autonomy. It is not a decision Blue Origin can afford to take lightly, given its founder’s respect for NASA and the future funding at stake.

“Amazon is an amazing company and Bezos has changed the world with it,” Weinzierl says. “But it’s nothing compared to, say, colonizing Mars and creating the second place on which a substantial number of humans live. That’s big. If you have grand goals of how to change the world, there’s nothing bigger than space.”

Back on earth, Weinzierl is looking forward to building up a robust treatment of a sector that hasn’t received much attention from economists or business schools as yet. In addition to the Blue Origin case, Weinzierl and his research associate Angela Acocella have written and taught a second case: “Astroscale, Space Debris, and Earth’s Orbital Commons.” That case focuses on how a technology being developed by a Singaporean startup may help to address the looming problem of accumulating space debris in Earth’s orbit. Both cases generated exceptional enthusiasm when taught at HBS for the first time this spring. And Weinzierl and Acocella have multiple additional space cases in the pipeline. In fact, Weinzierl hopes that some of his students may be inspired to launch their careers with New Space.

“The space sector is full of smart technical people. By its own admission, it’s short on smart business people, and short on social scientists,” Weinzierl says. “Right now, there’s a lot of room on the ground floor for students that either have a latent interest in space, or who are just smart business people that want to be part of a growing industry.”