Unilever and Brexit: How isolationist political movements impact supply chain decisions

Brexit introduced much uncertainty into Unilever's supply chain, and is already impacting strategic decisions. The extent of the impact hinges on the ultimate form that Brexit will take.

Unilever and Brexit: How isolationist political movements impact supply chain decisions.

On 23rd June 2016, the citizens of the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union. The GBP slumped over 10% against the USD on the day[1]. The UK had been a part of the European Community (EC, or the common market) since 1973. A reversal of over 4 decades worth of globalization and trade integration could have a significant impact on the supply chain of multi-national businesses such a Unilever.

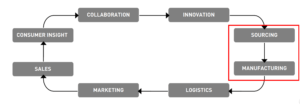

Unilever is one of the world’s best-known consumer goods companies, which operations in over 100 countries and sells products in over 190 countries, serving over 2.5 billion people in the world[2]. Annual turnover from the UK is nearly EUR 2bn[3], against a global turnover of EUR 52bn (EUR 13bn of which is from Europe). A brief look at Unilever’s current business model is shown in the figure below:

With respect to its UK operations, the “Sourcing” and “manufacturing” parts of the supply chain are subject to the largest volatility following the Brexit decision.

- Sourcing: A sharp rise in input costs has an immediate impact on the profitability of products and Unilever responded with an increase in prices (where possible) in the short-term. For a net commodity importer such as the U.K., a rise in input costs of wheat and oil in GBP terms immediately put pressure on the cost of Unilever products such as Marmite[4]. In the immediate aftermath of Brexit, Unilever chose to raise prices on some of its products in the UK, notably Marmite and PG Tips by 10%. This immediately triggered a widely publicized conflict with Britain’s largest supermarket Tesco which refused to pay the higher cost. The “Marmite Wars”, as it came to be known, was ultimately short-lived as Tesco relented. While price elasticity and bargaining power favored Unilever in this case, they almost certainly will contribute to decreased profitability in Unilever’s lesser known, price-inelastic products. For these products, Unilever will rely more heavily on currency hedging to mitigate the impact on its profitability.

- Manufacturing: In the medium term, Unilever will face pressure to further “localize” its manufacturing base. Given its global footprint, Unilever does diversify its manufacturing operations and tries to localize it production as far as possible. From the most recent annual report[5], Unilever operates 306 factories in 69 countries. Still, when compared to its overall footprint in 190 countries, there is a mismatch between its revenue footprint and cost footprint (most likely because of favorable labor arbitrage conditions). Specifically, in the context of European operations, the lack of trade barriers over four decades would have “globalized” the supply chain even more within Europe. Unilever management now faces key decisions on where it will make future growth investments and even where it will choose to headquarter[6][7].

In terms of further addressing these concerns, Unilever will have to take further step to “localize” its supply chain in Europe, and will most likely relocate manufacturing to EU countries where the labor arbitrage gap is still sizable such as Poland, Hungary and Romania. Of course, this will be to the detriment of the U.K, where long-term investment in the country will fall and consumers will be left to deal with rising inflationary pressures. At a global strategy level, Unilever will also need to continue to diversify away from Europe (where demand is flat/falling) and further into emerging markets in search of higher growth and profitability.

An open question facing Unilever as we look ahead is the exact form that Brexit will take following the negotiations between the UK and the EU government. At the heart of the uncertainty is where the UK will undergo a ‘soft’ Brexit or a ‘hard” one. In the ‘soft’ Brexit outcome, the trade frictions between the EU and UK will be minimal as free movement of production input (labor and capital) and output (goods and services) will be maintained, leaving Unilever to deal with just pricing decisions to maintain profitability. On the other hand, a ‘hard’ Brexit outcome where trade barriers and tariffs are re-introduced would necessitate wholesale changes to its supply chain setup as they run up against a limit on the actual price rises they can impose without a corresponding decline in market share.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jun/23/british-pound-given-boost-by-projected-remain-win-in-eu-referendum

[2] https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-annual-report-and-accounts-2016_tcm244-498880_en.pdf

[3] https://www.unilever.co.uk/about/who-we-are/introduction-to-unilever/unilever-in-the-uk/

[4] https://www.ft.com/content/1cbb6d34-9d29-11e6-8324-be63473ce146

[5] https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-annual-report-and-accounts-2016_tcm244-498880_en.pdf

[6] http://www.bbc.com/news/business-36544875

[7] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-04-07/london-or-rotterdam-unilever-set-to-test-may-s-brexit-strategy

The biggest question this begs is who really has the power in this situation. Theoretically, if the UK market was driving enough of the share of the Unilever business, then obviously this would have a marked impact on the business model for Unilever and would potentially raise a larger strategic question. However, given that the UK market is relatively small for Unilever at ~4% per your numbers, perhaps it’s more cost and resource effective for them to cut losses and move on to other markets where they can invest and more readily win back the same amount of market as they would lose with this new restrictive policy in the UK.

To me, this case raises an interesting strategic question for Unilever’s executives: Do they have a fiduciary duty to try to sway political policy? Your essay clearly highlights the negative impact of Brexit on Unilever. It begs the question, therefore, did Unilever’s executives appreciate the negative consequences of Brexit beforehand, and, if so, did they do enough to stop it from happening?

A review of press releases shows that Unilever executives hesitated to come out strongly on one side of the issue, with one statement saying, “”We cannot predict the consequences on the economy and subsequent impact on our operations in the UK” [1]. Moreover, Unilever executives hesitated to really rally their employees to vote against Brexit. A note to employees said, for example, “It is not for us to suggest how people might vote… but… we feel a responsibility to point out that Unilever would…, in our considered opinion, be negatively impacted” [2].

Given the significant impact of Brexit on Unilever, I believe executives should have been more proactive and forceful in these public statements.

[1] “Unilever bosses say firm ‘would be hit by Brexit’,” BBC News, June 16, 2016, [http://www.bbc.com/news/business-36544875], accessed November 2017.

[2] Ibid.

I’m intrigued by the above comment – do executives have a fiduciary duty to try to sway public policy in their interest? In the case of Brexit, it may seem simple. I’d wager most of our class thinks Brexit is bad for the UK and bad for the world. We’re therefore more likely to buy the argument that businesses should have caused more of a storm around the impact of Brexit on UK business (though to be fair I think this point was very much at the forefront of the public debate).

Most large businesses, of course, do have lobbying arms dedicated to exactly this cause – trying to sway public policy decisions. But if businesses have a fiduciary duty to try to sway political discourse, then we also believe, for example, that businesses have a fiduciary duty to support things like the current US tax plan which significantly reduces corporate taxes. The end result of this logic would be that businesses have a fiduciary duty to support a 0% corporate tax rate. But others might argue that a 0% corporate tax rate is harmful to society at large by failing to provide enough funding for public goods… Which leads me to this point of view: public policy decisions are complicated. What benefits a business in the short-term may hurt it in the long-term. Arguing that businesses have a fiduciary duty to take one side or another in a policy debate doesn’t make a lot of sense. Businesses are a major force in our society and they should weigh in where they think they can make a difference – but that difference should be defined much more broadly than fiduciary responsibilities.

The essay alludes to fascinating links between macroeconomic expectations and supply chain decisions. I agree that the Brexit primarily affects the Sourcing and Manufacturing parts of the supply chain. It is also evident that international sourcing becomes more expensive in the face of the weakening British Pound (GBP). However, given the complex interaction of many economic variables at work, Unilever might actually benefit from increasing its manufacturing footprint in the UK.

The relative weakness of the UK economy makes manufacturing in the UK more competitive. The GBP lost about 15% in value vs. the EUR since the Brexit [1], while median income of employees (and thus labor cost) remained largely flat [2]. Keeping other factors constant, this means that a buyer – e.g., in Canada – can now purchase UK products at a relative discount, which will increase international demand for UK products. More precisely, the weaker GBP has two opposing effects for a UK manufacturer:

(A) it increases raw material costs not incurred in GBP (“bad” for UK manufacturers);

(B) it decreases relative (international) market prices of goods manufactured in the UK (“good” for UK manufacturers).

The above thought experiment, however, only holds true if the net effect is positive, i.e. if effect (B) exceeds effect (A). A positive net effect is more likely if the local value-add as a share of total Cost of Goods Sold is high (i.e., if the raw materials portion of total COGS is low).

In sum, given the economic forces at work, Unilever might actually benefit from “over-indexing” in UK manufacturing and choose the UK over EU countries such as Poland or Hungary as a manufacturing hub. This decision, however, hinges on some key assumptions:

* Unilever can produce products in the UK that (i) require a significant local value add, (ii) incur relatively low international sourcing costs, and (iii) permit oversea (ex-EU) shipping, given potential trade restrictions from the EU.

* The GBP continues to be significantly weaker compared to the EUR.

* Availability of labor in the UK does not decrease significantly, e.g., through a “hard Brexit” that could curtail the free movement of labor, which would push up wages.

_____

[1] http://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=GBP&to=EUR&view=2Y

[2] https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/ nowcastinghouseholdincomeintheuk/financialyearending2017

(all accessed on Nov. 27, 2017)

I completely agree that Unilever needs to diversify outside of Europe against the flattening market and the potential barriers being imposed on the UK, especially if there is a hard Brexit. Very quickly, the UK could become an all-or-nothing market for suppliers who choose to source/manufacture within the UK, or choose to just not sell there at all there if sourcing and manufacturing is done outside. A hard Brexit here could very quickly lead to the latter, and prevent the former for many companies that don’t want to just produce in the UK for revenues in that market alone (against the tariffs introduced if shipping from UK to EU).

I think many of the points presented above are excellent. However, I think Unilever may have enough power behind their brands to pass on any tariffs incurred from restrictive trade policies to consumers.

Although the Brexit poses a clear and relevant threat to Unilever’s supply chain in the UK and the EU, I believe that the multinational consumer goods company should not take any material actions yet, mainly if they involve relevant investments (e.g. moving plants or headquarters, switching suppliers, etc.). I believe this for a reason: I don’t think it would be an efficient use of capital given the risk-return profile of such investments, considering the other investment options that the company could pursue.

In my view, the uncertainty around Brexit negotiations is so great that any decision directly linked to “potential outcomes” seems way to risky. Moreover, if compared to opportunities in emerging and markets which, as the author mentions, exhibit very attractive growth rates and higher profitability, investments in changes in the UK seem even less attractive.

That being said, I do believe that there is value in analyzing potential scenarios of Brexit outcomes, to identify potential actions to adapt to each scenario. While brainstorming around potential changes in the production footprint, assessing viability of increasing UK suppliers, etc. might make sense, I believe that no significant changes and investments should be made – yet.

I think that this is an excellent company to use as an example in the UK/EU events. As the UK moves towards a more isolationist economy, the question remaining on everybody’s mind will be how much more expensive has this made things and what will happen to our talent? Interestingly with GB based consumer goods companies, right after the vote to leave was announced, the stock price climbed significantly. Reason being that Unilever’s revenues are substantially received from outside the UK. With that being said, the higher valuation can likely be attributed to the foreign exchange benefit that Unilever will receive in lieu of the weak sterling. How then can Unilever take further advantage of the foreign exchange movement to hedge against these escalating trade costs?