Traveling to Iceland? Perhaps think twice.

With today’s technology, air travel is hugely taxing on the environment. However, companies, such as Icelandair, are working to ensure we can continue to enjoy the world’s beauty.

This week, over 150 Harvard Business School students will travel to Iceland, a country known for its natural beauty and “free” airplane layovers. Their round trip flights between Boston and Reykjavik will emit 100 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, an amount of greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to driving 217,421 miles in an average passenger vehicle.[1],[2]

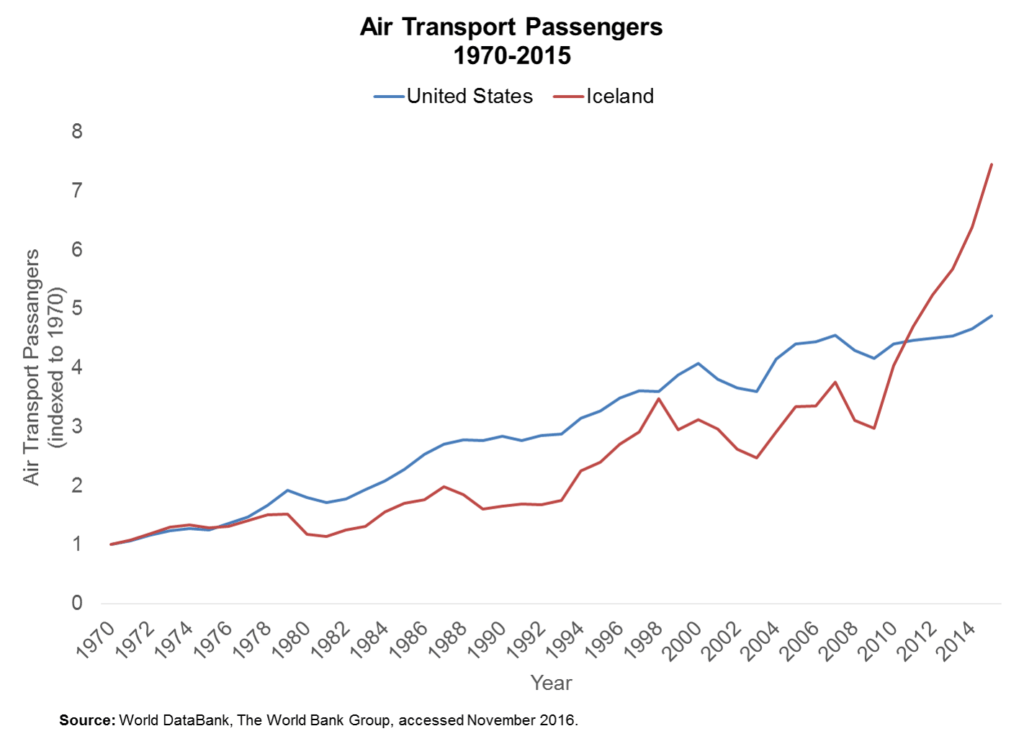

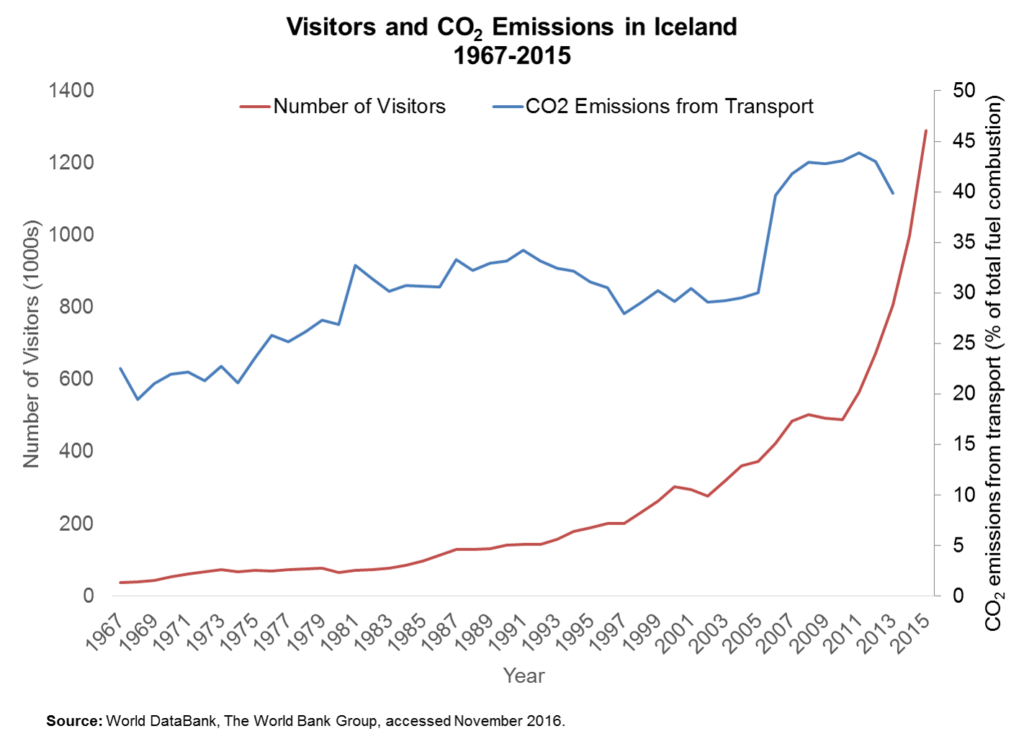

However, HBS students are not the only ones eager to visit Iceland. Tourists are flocking to the island at shocking rates. In 2015, 1.3 million people traveled to Iceland, an increase of 164% over 2010 figures.[3] Between 2008 and 2015, air transport to Iceland increased 140%, compared to a mere increase of 14% in the United States.[4]

The increase in tourism in Iceland poses significant climate change challenges for Icelandic companies in the tourism sector.[5] Icelandair, Iceland’s leading airline by market share, is one example of such company affected by climate change.[6] In particular, Icelandair is faced with the following challenges:

- The drastic increase in air travel has a significant impact on greenhouse gas emissions. A round trip flight from Boston to Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland, emits approximately 133 tons of CO2 or 0.67 tons of CO2 per passenger.[7] That’s a whopping 867,100 tons of CO2 emissions as a result of all air travel to and from Iceland in 2015.[8] To offset this amount of CO2 emissions, we would need to plant 744,618 acres of U.S. forests in one year, not an easy feat.[9]

- Climate change causes volatility in the tourism industry. Research indicates that melting glaciers in Iceland due to rising temperatures could lead to an increase in the number of erupted volcanos in Iceland to as much as one in seven years.[10] As a result of the erratic nature of natural disasters, tourists may be deterred from visiting the country, especially following a volcanic eruption. Moreover, a sporadic decline in visitors due to events triggered by climate change could drastically effect Icelandair’s revenues, a situation they must prepare for.

These two challenges highlight the interrelated nature of climate change and tourism. Thus, there is not only an ethical case for addressing climate change, but there is also a business case for doing so.

As outlined in Icelandair’s environmental policy, the company is taking a proactive approach to mitigating their carbon footprint. Their environmental policy includes:

- Development of greener aircraft. Icelandair has made several technological improvements to its aircraft to increase fuel efficiency. For example, the company installed winglets on their primary aircraft, B757-200s. These winglets “reduce fuel consumption by over 4% by diminishing wind resistance,” thereby reducing carbon emissions.[11]

- Use of renewable energy instead of fossil fuels. Icelandair’s headquarters relies on electricity from 100% renewable sources, namely hydropower and geothermal power. In addition, the office puts a timer on the lights so they automatically shut off at the end of the day.[12]

- Partnership with the Kolviður Iceland Carbon Fund to facilitate carbon consciousness. Through Icelandair’s partnership with the Kolviður Iceland Carbon Fund, passengers can choose to offset the carbon emissions generated by their flight during the ticket-buying process. The fund uses the money to plant trees and grow forests, a method for sequestering carbon.[13]

Icelandair is aiming for carbon neutral growth by 2020 and zero emissions by 2050.[14] To achieve this goal, and also address volatility in tourism as a result of climate change, Icelandair may also want to consider the following strategies:

- Partner with the Government of Iceland to develop a robust disaster relief plan for extreme weather events caused by climate change. Tourism is one of the biggest industries in Iceland, and an extreme weather event, such as a volcanic eruption, could have a devastating impact on companies in the tourism sector. Therefore, Icelandair should work with the Government of Iceland to build a disaster relief plan that would be equipped to handle the large number of tourists who visit the country at any given time. The plan would serve the dual-purpose of ensuring tourists in Iceland are safe if a natural disaster occurs and reassuring potential tourists who may be reluctant to travel to Iceland given the increased likelihood of a natural disaster.

- Limit flights to Iceland that are not full to capacity. As we have seen, air travel is quite onerous on the environment. Likewise, flights that are not at capacity generate less revenue. Given the environmental and financial impacts of operating partially-empty aircraft, Icelandair should limit the amount of flights that are not at capacity.

So, when you travel to Iceland this week, think about your carbon footprint. Iceland’s glaciers and lagoons may not be around forever; however, Icelandair is committed to protecting our climate – and international travel experiences. The question is: are you?

Interested in calculating your Carbon footprint and seeing how your air travel affects the environment? Check out these great resources.

Word Count: 799

[1] Calculation assumes the following: (1) roundtrip between Boston and Reykjavik is approximately 5,000 miles; (2) airplane is a Boeing 757-200, the most common airplane in the Icelandair fleet; and (3) the plane is full to capacity. Icelandair, “Icelandair Fleet,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/our-fleet/, accessed November 2016. BlueSkyModel, “1 air mile,” http://blueskymodel.org/air-mile, accessed November 2016.

[2] US Environmental Protection Agency, “Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator,” https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator, accessed November 2016.

[3] World DataBank, The World Bank Group, accessed November 2016.

[4] World DataBank, The World Bank Group, accessed November 2016.

[5] The World Tourism Organization, “Climate Change & Tourism,” http://sdt.unwto.org/en/content/climate-change-tourism, accessed November 2016.

[6] CAPA Centre for Aviation, “Icelandair: Atlantic niche drives strong growth in 2014, but 2015 profit growth relies on lower fuel,” February 9, 2015, http://centreforaviation.com/analysis/icelandair-atlantic-niche-drives-strong-growth-in-2014-but-2015-profit-growth-relies-on-lower-fuel-208678, accessed November 2016.

[7] Calculation assumes the following: (1) roundtrip between Boston and Reykjavik is approximately 5,000 miles; (2) airplane is a Boeing 757-200, the most common airplane in the Icelandair fleet; and (3) the plane is full to capacity. Icelandair, “Icelandair Fleet,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/our-fleet/, accessed November 2016. BlueSkyModel, “1 air mile,” http://blueskymodel.org/air-mile, accessed November 2016.

[8] This is a lower bound. Calculation assumes everyone has a roundtrip of 5,000 miles (roundtrip distance between Boston and Reykjavik). In reality, many flights are probably coming from further away given Boston’s relatively close location.

[9] US Environmental Protection Agency, “Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator,” https://www.epa.gov/energy/greenhouse-gas-equivalencies-calculator, accessed November 2016.

[10] Kathleen Compton, Richard A. Bennett, and Sigrún Hreinsdóttir, “Climate‐driven vertical acceleration of Icelandic crust measured by continuous GPS geodesy,” Geophysical Research Letters 42, no. 3 (2015): 743-750, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/doi/10.1002/2014GL062446/full, accessed November 2016.

[11] Icelandair, “Icelandair’s Environmental Policy,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/environmental-policy/, November 2016.

[12] Icelandair, “Icelandair’s Environmental Policy,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/environmental-policy/, November 2016.

[13] Icelandair, “Icelandair’s Environmental Policy,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/environmental-policy/, November 2016.

[14] Icelandair, “Icelandair’s Environmental Policy,” http://www.icelandair.us/information/about-icelandair/environmental-policy/, November 2016.

Your blog caught my attention as I was planning to travel to Iceland in the near future! I am actually quite shocked at how much CO2 (not to mention the equivalent number of trees that would need to be planted to offset it) a flight to Iceland generates. I like that Icelandic air is currently focused on building greener aircraft (it seems like an easy win), but I do wonder if some of the technological improvements necessary to make these aircraft as green as possible will increase the cost of the flight and conversely hurt their revenue. Its quite possible that they will stop short of building the most green aircraft possible and just focus on marginal improvements like wing design to reduce fuel use, given the cost/revenue trade off. Regarding your suggestion of limiting flights to only those that are full capacity, I think this will be extremely challenging if not business-suicide. I think there may be huge customer backlash around convenience, not to mention issues of getting full capacity during “low season”. This could potentially be a huge revenue loss to them and an opportunity for a competitor (i.e jet blue) to establish a dominance.

Rebecca – a highly relevant and provocative article. I’m going to Iceland as well this next weekend, and I think it is very important for all of us to be aware of our consequences. I’ll avoid repeating the aforementioned comment viewable to me. Regarding the consumer (a.k.a. myself) several questions arise: (a) Iceland vs. ______? (b) Limit travel overall? (c) Reduce all my emissions?

Iceland vs. ______. Is the volume of emissions or the geographical concentration of emissions via Iceland flights the key consideration for consumers to weigh? For instance, if I were instead to travel an equivalent distance this coming weekend, but to a different geography, would that be a better choice? Or is Icelandair less efficient than other craft? Or would a shorter traveling distance this weekend (to say, Miami), keep with in line the ethical framework underpinning the article?

Limit travel overall. In spite of the above questions (which would be, if I were you, very annoying), I gather the spirit of the article’s message to the consumer is more along the lines of this: “flying around the world emits a lot of GHGs; be mindful.” In that case, I feel kind of guilty for traveling home for Christmas. I hope those planes are at capacity, and if there’s more I could do to get those planes to capacity, I suppose I would try, but that would only reduce the per-person GHGs (thus my individual guilt) — but that plane’s gonna fly whether I’m on it or not at this point. As is the plane to Iceland next weekend. The central point: how can I ethically justify any plane travel?

Relatedly, another message I gather is that overall, we as consumers should seek to reduce our overall environmental impacts, which I agree with. Fly less, dispose of waste smartly, limit shopping for new clothes, take a reusable bag to the grocery store, etc. That said, the implication this ethical framework at its core is that every unit of GHG emission per person is a unit of “unethical,” so the only way to really redeem myself is to get to 0 GHG…in which case, given the impossibility of this in a vacuum, it would only be ethical for me not to exist.

The silver lining of that last concern is that – of course – we don’t live as individuals in a vacuum! Especially in our unique position at HBS as leaders who make a difference, we can do more than be carbon-zero by bringing people, organizations, and the world together to reduce GHGs, to negative GHGs per person.

This is a very interesting post. I think that a partnership between Icelandair and the government could be a major solution to managing the carbon footprint of Icelandair. Perhaps the government can work with the airline company to specify designated travel months for consumers that will help protect the environment. The decrease in volume of flights would obviously have a huge impact on Icelandair’s revenues. To account for this drop in volume of flights, Icelandair could respond with dramatically raising prices, deterring consumers away from traveling to this destination at all. However, because of the rich beauty that this country has to offer, I think that a majority of tourists would not negatively respond to an increase in price. If Icelandair is transparent about why their prices have increased and if the company states its effort to preserve the beauty of Iceland, I believe that consumers will appreciate the company’s sustainability efforts and even begin to realize their own impact on the well-being of the environment (the idea that they should be more conscious of their own travel and its impact on the environment). Customers care about fair pricing, and if Icelandair is transparent and public about their efforts to maintain the beauty of its country, I think this can help mitigate the potential customer attrition from price hikes.

In line with Amira’s comment above, an important question is whether the recent increase in flights to Iceland corresponds to a decrease in flights to other destinations. Assuming aircraft fuel use per mile is the same, and that a flight to Iceland has the same amount of people on it as a flight to any other potential destination, there’s 1:1 destination switching, the increase in flights to Iceland could actually be decreasing GHG emissions. (I realize all of these are shaky assumptions)

For example, if there was a 1:1 switch from London to Iceland, you’d have the following, courtesy of TravelMath.com

* Iceland 1-way flight distance: 2,437 miles

* London 1-way flight distance: 3,281 miles

If this were the case, and all the assumptions above hold, your switching destinations from Iceland to London would avoid an extra 26% GHG emissions.

But, glad they’re trying to address their carbon emissions.

Agree with Rob’s comment above. Saving energy and avoiding GHG emissions in civil aviation should be considered at a global network level to make sure we really achieve a solid outcome.

My question would be on the potential impact of “limiting flights to Iceland that are not full to capacity”. From an energy-saving perspective, this idea makes perfect sense to reduce average GHG emissions per capita by reducing partially-empty flights. However, financially it would directly draw down the revenue of Iceland Air, since most of any flight of any airline companies would not be accurately full to capacity. It would also cause limited flight choices for tourists, and thus decrease their desire of choosing Iceland as their destination – finally cause a slow development of Iceland tourism industry.

Thanks for a really well thought-out post, Rebecca. I agree with others that your topic struck me as someone who would love to experience Iceland’s natural beauty, but has to reconcile that with the significant environmental harm that comes with travelling to the very location I’d like to see and preserve.

I agree with your suggestion that Icelandair should partner with the government to create a plan of action for extreme environmental episodes. I would, actually, argue to take it one step further and coordinate with the airline associations or governments of countries that passengers most frequently travel to in connection with Icelandair’s “free layovers,” that you mentioned earlier. I was in Dublin waiting for a flight to London in 2010 when the Eyjafjallajökull volcano erupted and halted all air travel. Although the eruption itself was not large by volcanic standards, the dust traveled quite far and remained in the atmosphere longer than experts had seen before, causing air travel delays in Europe and the North Atlantic for close to a month. Partnering with surrounding governments seems like a realistic way to acknowledge how interconnected air travel is, and how frequently these episodes will occur moving forward.

I do have questions about limiting travel to Iceland based on airline capacity because I wonder how much the country’s economy relies upon tourism. If the financial benefits from tourism better allow Iceland to invest in its natural resources then making it more difficult to travel there might not have the intended benefits you describe.

Rebecca,

Thanks for this post! Like many at this school, I’ve travelled hundreds of thousands of miles in recent years, with little thought to the emissions implications. Thanks for bringing this to my (our) attention.

If i’m summarizing, I’d put your potential solutions into two categories:

1. Limit travel (think twice about traveling to Iceland, don’t fly flights that aren’t full, etc)

2. Mitigate the impact of travel (carbon offsets, better fuel efficiency, etc)

I’d be curious about where you see the bigger potential for improvement. Is decreasing the amount of travel that takes place really a feasible option? Or should we assume people will travel as they want, and focus on mitigating the impact of that travel?

Spencer

Rebecca,

Thank you for your thoughtful post. What I struggle to reconcile is the conflict between the recommendations (specifically, not traveling to Iceland and limiting flights to Iceland) and the ultimate business concern of climate change deterring tourists from visiting the country. While I agree with the ethical argument that we should be concerned with preserving the glaciers, limiting the number of flights and requiring investment in Icelandair planes will cause an increase in flight prices and a decrease in the number of tourists. As 12% of the country’s total workforce is employed in tourism-related industries and 5% of the country’s GDP is directly linked to tourism, a preemptive decrease in tourism will have a notable impact on Iceland’s economy. To the extent the performance of local businesses and the government’s tax revenues suffers, I assume there would be less capital available to invest in clean energy solutions. I believe some other comments have also noted that if Iceland becomes more expensive to travel to, will these tourists instead fly to a place like Mexico and emit the same amount of carbon dioxide? This exemplifies why this issue is so complex, but wouldn’t these recommendations result in Iceland (and specifically Icelandair) falling on their own sword to no effect?

Thanks again!

Jess Delfino

Great timing on the article. While Iceland’s GDP is boosted in the short-term by the tourism industry, the country’s GDP is bound to suffer in the long run if the country cannot sustain its natural beauty, which is one of the main demand generators for tourism. To echo some of the previous comments, Iceland can simply reduce the number of visitors to the country and/or encourage more eco-friendly modes of transportation when visiting the country. For example, instead of encouraging individual car rentals, Iceland can institute public transit to the popular destinations. Also, a more drastic approach is for Iceland to close off specific regions to foreign visitors to further protect the unique eco-system.

Thanks Rebecca for the interesting post. I think it’s easy to forget the environmental impact of air travel so it’s great to have a reminder.

I agree that actions like building more environmentally friendly aircraft are a great first step and I hope that other airlines adopt these policies as well. I wonder if it would be possible for the government of Iceland to impose a small tax on each ticket that would go toward pro-environment activities without raising ticket prices enough to effect demand? It would be interesting to do a price sensitivity analysis to determine if this is feasible. I’m not sure what Iceland currently charges, but given some of the countries I’ve traveled to tack on hefty taxes and visa fees I would be interested to know if Iceland is taking full advantage of these revenue sources to handle challenges like climate change.

Great post! Areas like Iceland that rely on their natural biodiversity for tourism face such a unique dilemma as you pointed out, on the one hand driving climate change by bringing more and more tourists to their land and on the other fearing climate change and the impact it could have on that land. This reminds me very much of the Galapagos, an area that has strictly monitored travel in order to minimize the impact that tourists have on the local environment, which is so fragile and easily disturbed. They require all passengers to be part of a tour group and require all tour groups to minimize waste, conserve water and energy, use biodegradable products (such as soap and shampoo), and source local products to avoid introducing new species into the environment [1]. This type of ecotourism is not unique; countries like New Zealand also practice strict standards and impose ridiculously high fines for breaching them. For example, you can be fined anywhere from $400-100,000 for bringing in food of any kind, plants, animals, equipment used with animals, and any clothing used for camping or hiking that has foreign dirt on it [2]. I wonder if Iceland might be able to impose the same standards and fees to their tourism economy. If so, these fees could be used to fund green programs and offset carbon emissions.

1. http://www.galapagos.org/travel/travel/sustainable-tourism/

2. http://www.customs.govt.nz/features/prohibited/imports/Pages/default.aspx

I am among the people who have a plan to visit Iceland during winter break. I didn’t realize how much impact planes has on the environment. I am very impressed with Icelandair effort to combat climate change. They are certainly fully aware of the issue and try to treat the issue right away. This got me thinking about situation in my home country, Thailand. Like Iceland, Thailand rely on its natural beauty e.g., beaches, mountains, and waterfalls to attract tourists. However, unlike Iceland, Thailand has a very poor management of how to sustain its natural beauty. Even at the most basic level e.g., littering. It is quite sad and shocking how far we (Thais) has to improve to help both ourselves and the world.

I do think that your suggestion of limiting the number of flights that are not at full capacity makes sense. I am just worried about the execution of such a solution. many flights tend to fill out at the last minute, so it would be hard to stop a flight from taking off unless it is filled.

Hi Rebecca – Thanks for putting together a great post. I am heading to Iceland this week ʘ‿ʘ! Hearing about the growth of their tourism industry I cannot help but smile for the people of Iceland who have had a rough few decades.

I am not sure if you remember, but preceding our own recession in 2008, Iceland had their own implosion. The once sleepy fishing nation vaulted to global prominence as a financial center, whose three largest banks grew to 10x the size of the economy! Unfortunately much of the growth was too good to be true and the banks collapsed requiring an IMF bailout [1]. Back to your post, I am hopeful that Iceland can be measured with how it manages the influx of tourism, their new “golden goose” so to speak. If they do not take a measured approach and deliberately protect their natural resources from both climate change and human degradation, the party may be short lived. I am hopeful that they will do the right thing and preserve Iceland for the long term so that my kids can too visit the Blue Lagoon and see the Northern Lights.

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/06/17/the-miraculous-story-of-iceland/

Rebecca,

Thanks for this insightful and provocative post! My main question for you is how do you suggest countries like Iceland balance the need to attract tourism for economic growth with the environmental impact all these flights may have? You have clearly articulated the negative effects of tourist air travel, but the importance of the economic stimulus these tourists provide to Iceland and many other small countries cannot be overlooked. In many of the countries most effected by climate change tourism is a crucial part of the economy. If you were the head of Iceland’s tourism bureau or economic department, how would you handle this question? Would you actually be willing to reduce the number of tourists and give up all the stimulus that comes with them?

Rebecca,

Very interesting article. I liked a lot the part that you relate how global warming can potentially increase the tourism industry in Iceland by an increase in natural disasters, and how this could eventually backfire for Icelandair. As you mentioned in the article, this gives the airline a double incentive to address the issues of their emissions, something I found your point of view fascinating as many companies sometimes struggle to see a relation between the initial investment in sustainability and positive impact in its revenues.

However I am having trouble understanding how limiting flights that aren’t full to Iceland could be beneficial to anyone. If the company decides to make that flight, it is most likely because they are making a profit with it, however small it may be. On the other hand, airline companies try to maximize flying time of their aircrafts so if that flight were to be cancelled the company will probably reschedule it to fly somewhere else, and the emissions will exist anyways. This last point then only has a negative impact on the country, who is missing out on tourist spending.

But, despite my last point I like the idea in general and how the airline sees the future negative impact not only for them but also for the country, and the fact that they are trying to address this issue. I also like the potential cooperation between the airline and the government to try and maintain the tourism industry relevant for the country.

Hey Becca,

I just had to comment on this post because Iceland has been on my travel bucket list for the last couple of years. You make good points about how air travel emits greenhouse gases, exacerbating global warming, but obviously these results are not isolated to IcelandAir.Its goals to use renewable energy and a greener aircraft are admirable, but I’d be interested in knowing what market share Iceland Air has compared to WowAir and other companies that shuttle tourists to the country. If there could be a coordinated airline industry-wide shift towards sustainability, the impact would be amazing. Additionally, I noticed increased tourism -> more flights to Iceland -> increased GHG emission -> melting glaciers -> volcanic eruptions -> decreased tourism -> less flights to Iceland. So, might this be a self-regulating system? Just a thought.