To use fertilizer or not use fertilizer? That is the question

The story of how for the last 10 years Esoko, a for-profit digital technology company in Africa, is giving smallholder farmers the right information at the right time.

Feeding ~10 billion people, not an easy task

By 2050, 9.7 billion people will live in this planet[1]. In order to feed 2050 global population, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States (FAO) estimates that world food production will need to increase by ~70%[2]. Of all the world regions, Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is projected to increase the fastest (114%)[3]. The good news is that research shows that Africa’s smallholder farmers will be more than capable of feeding the African continent.[4] The bad news is that African smallholder farmers will need to double their current crop production in order to feed their continent.[5]

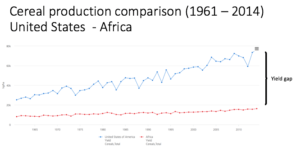

In the last 50, the world, and in particular the United States of America, has seen tremendous improvements in their crop yields (yield of a crop per unit area of land cultivation) thanks to adapted seeds and fertilizers, best-in-class agronomic practices and major technology deployment. On the other hand, for the last 50 years, Africa has seen almost none crop yields improvements (see graph below – FAO.com). If Africa wants to feed itself, it needs to catch up, and it needs to do it fast!

Playing catch-up? Digital technology can help

We know that Africa’s smallholders are more than capable of producing enough food to feed the continent; but we also know that in order to do it they need to increase their yields by using the right seeds and fertilizer, along with the implementation of the best agronomic practices. So, why have smallholder farmers not adopted these practices and have used these seeds and fertilizers? Because so far they have had no incentives to do it. The infrastructure to link most smallholders to markets simply does not exist, which means that farmers have very few incentives to increase their productivity in order to generate surpluses to sell. Digital technology can link, and has been linking, smallholder farmers to markets. In other words, digital technology was created incentives to make smallholder farmers produce more. Esoko, a for-profit company with the mission to make agriculture a profitable business for smallholder farmers, has been linking smallholder farmers to markets for the last 10 years.

Esoko: E-markets. Soko is market in Swahili

Esoko is using digital technology to link historically fragmented markets. There are thousands of organizations around Africa that are trying to talk to farmers to improve their yields. African governments, ministries of agricultures, multilateral organizations (e.g., World Bank), donors (e.g., The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), businesses (e.g., John Deere, seeds and fertilizers companies) and social enterprises want to reach out to farmers in villages to make them use new seeds, use the right amounts of fertilizers, organize as a group to get microfinance loans. They also want to tell them what they should grow, depending on fluctuating market prices, and explain to them how to link to potential market. That said, talking to farmers is difficult! Smallholder farmers are spread in vast areas, and infrastructure is very poor. It is not scalable to have personal one-to-one interactions. Esoko connects players in a scalable way using mobile technology.

Right Information at the right time

A farmer needs to know exactly when he or she should plant, if there is a disease outbreak, if rain is coming or not, if they should use fertilizer or not, if prices of a certain commodity are going up or down, if there is a drought or flood! Agriculture is about protocols, doing the right things at the right time. Esoko uses SMS and voice messages (to address literacy issues) to connect different players. The information they communicate is divided in four main areas[6]: Market prices, Potential, buyers, Rain forecasts and Crop protocols.

Esoko is currently working in 15 African countries. Esoko creates personalized solutions for each of its clients. Esoko makes money by charging $10,000 USD to $100,000 USD, depending on the complexity of the product they are selling. Esoko has created more than a dozen solutions for business that are trying to convert farmers into consumers, and for governments and NGOs that want to improve the livelihood of their beneficiaries.

$3 million in profits and $450 million into the smallholder farmer community

Esoko is expected to make a profit of $3 million USD by 2020. In addition, by 2020, it also expects to have targeted 3,000,000 smallholder farmers each getting a $150 USD of additional revenue per year, which translates in $450 million USD of transfer value into the smallholder farmer community[7].

Looking ahead: new geographies and data licensing

Moving ahead, Esoko should consider two avenues of growth: moving to other markets (e.g., Latin America and India) and data licensing to companies such as Thomson Reuters of the data they have collected in the last 10 years.

(793 words)

Sources:

[1] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. “World population projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050.” 29 July 2015, New York.

[2] FAO. “High Level Expect Forum: How to Feed the World 2050. Global agriculture towards 2050.” Rome 12 – 13 October 2009.

[3] FAO. “High Level Expect Forum: How to Feed the World 2050. Global agriculture towards 2050.” Rome 12 – 13 October 2009.

[4] Annan, Kofi and Sam Dryden. “Food and the Transformation of Africa: Getting Smallholders Connected.” November/December 2015 Issue.

[5] Klucas, Gillian. “Yield gap study highlights potential for higher crop yields in Africa”. September 30, 2015.

[6] Esoko. Clients. Esoko website. https://esoko.com. Accessed November 2016.

[7] Esoko. Esoko website. https://esoko.com. Accessed November 2016.

Past few weeks have been very important to shake off my arrogance about agriculture: Contrary to my belief before – the knowledge about what has to be done on the field when is very static and is passed onto the next generation through apprenticeship – the actions to be taken are so dependent on the state of the crops and weather, very dynamic variables, that there is a great need for up-to-date and relevant information. There is a very big opportunity for digital knowledge, with low cost to produce, update, and distribute, to create significant value.

As you very well pointed out in the post, this can be a great win-win situation: Going forward, Esoko could put less financial burden on the farmers by monetizing the data it produces from the farmers and farmers could utilize Esoko to access critical data for higher yields.

Excited to see how it plays out.

Amazing post Cami. I am very glad to see companies such as Esoko are being created. The two features that stroke me the most are:

– Being for-profit: I cannot foresee an end to the inequality in Africa’s access to information that does not pass by making business there attractive from an investor’s perspective. Esoko expects to be financially viable and that might attract additional companies to this space.

– Diversification of their revenue stream: as you mentioned, the data they collect is extremely valuable and shall be used to reduce the burden on farmers. It is the best example of how digital innovation can create in itself innovation, ie by selling the data I get more revenues that can be used to spread information and increase crop yield, which in turn generates more data and more revenues.

Love this post, Cami! I can see a very obvious parallel to the ITC case we discussed a couple of weeks ago, especially in terms of the information flow between the company and the farmers. They have used technology in a smart and efficient way to overcome the challenge that the farmers’ physical locations pose. The company also reminds me of M-Pesa and other mobile payment companies that aim to reach underserved consumers in rural areas who lack access to physical infrastructure. Some of the problems these companies have faced have been regulatory, as each country they move into has different laws regarding banking and financial transactions. I can’t think of any similar regulatory issues that Esoko could face, but I would be interested in learning about potential challenges they could face as they expand into new markets.