The Unforeseen Cost of Fast Fashion

Fast fashion is fundamentally antithetical to sustainability, but H&M is leading the charge to minimize its environmental impact.

H&M and the Fast Fashion Industry

H&M Group is the second largest apparel retailer in the world with 4,200 stores in 64 countries1. It is composed of six brands and sells an estimated 550M garments per year2. Similar to Inditex – the world’s largest apparel retailer – H&M operates on a ‘fast fashion’ model: producing clothing at extremely low prices, encouraging customers to dispose of garments after just a few wears to refresh their wardrobes with the newest fashion trends.

Fast fashion garners many critics for driving clothing to landfills, engaging in unfair labor practices, and contributing to 10% of global carbon emissions3. In response, H&M has developed a robust sustainability program. Several initiatives within this program are aimed directly at reducing its contribution to climate change.

Climate Change-Induced Risks to H&M

The physical effects of climate change will likely impact H&M’s textile suppliers. Rising temperatures allow pests to thrive in agricultural crops4, potentially damaging cotton and flax plant (the source of linen fabrics) growth5. A decline in the supply of cotton and linen may result in textile shortages or increased prices, impacting H&M’s ability to manufacture cotton and linen garments. Because a significant portion of fast fashion pieces are made from synthetic fabric, however, the potential risk to cotton and linen is likely to be of minimal concern to H&M. Instead, H&M is more concerned with limiting its own environmental impacts.

H&M’s Climate Change-Related Sustainability Initiatives

Climate change-related sustainability initiatives at H&M are comprised of three primary goals: 1. Increase the use of renewable energy in stores, offices, and warehouses. Impressively, H&M reports that the renewable portion of energy used in these locations has increased from 15% in 2011 to 78% in 20156. Installing windmills and solar panels on warehouses and IT data centers and reducing electricity usage in stores has contributed to this progress. Additionally, heat generated from IT data center cooling systems is used to heat apartments, maximizing the efficiency of energy used. As a result of these practices, H&M’s CO2 equivalents dropped from 290K tonnes in 2011 to 152K tonnes in 2015.

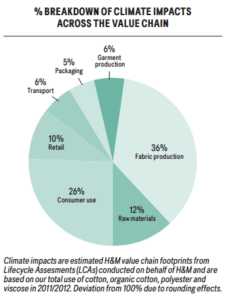

H&M has estimated that 10% of the CO2e emitted in a product’s lifestyle is a result of H&M’s retail operations. Another 36% comes from fabric production, and 26% come from caring for pieces at home. Accordingly, its other two climate change-related initiatives address other stages of the garment lifecycle: 2. Implement a supplier sustainability assessment program to support supplier adoption of sustainable practices. Additionally, H&M’s sustainability report indicates its intent to choose organic cotton (vs. conventional cotton) for its lower carbon impact. H&M has not stated quantitative goals for this initiative. 3. Ensure that 100% of transport service providers are registered with national organizations that track and support efficient energy usage in transportation. In North America, this entity is SmartWay, a subsidiary of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency7. Per its 2015 sustainability report, H&M has already reached this goal and continues to monitor its suppliers.

Recommended actions

While H&M’s sustainability initiatives and progress-to-date are admirable, the company needs to aggressively address the 36% of garment’s carbon impact attributed to fabric production. This can be achieved through increasingly careful fabric sourcing and selection. 1. Use of organic cotton (vs. conventional cotton) only. The International Trade Center confirms that the lack of pesticide use in organic cotton leads to a lower carbon impact than that of conventional cotton5. 2. Reduce the proportion of garments made from synthetic materials. The fashion industry’s use of synthetic fabrics in comparison to cotton and linen is quickly growing – this is partly because the world’s total cotton yield simply cannot meet demand for the 150 billion garments produced each year8. Manufacturing nylon contributes approximately 10% to the increase in atmospheric nitrous oxide, one molecule of which is 200CO2e9. Plastic fibers from synthetic clothing contaminate fresh water supply, exacerbating the risks to a resource already impacted by climate change10.

As the #2 global player, H&M should lead the charge in guiding the apparel industry towards sourcing organic, natural fabrics and reducing the proportion of garments made from synthetic materials. In response, textile suppliers will be forced to quickly adjust their practices to meet the demands of the fashion behemoth. While the fast fashion industry is fundamentally antithetical to sustainable practices, H&M should continue seeks new opportunities to minimize its contribution to climate change.

(Word count: 719)

- H&M Group Website, “About Us” November 3, 2016. <http://about.hm.com/en/about-us/markets-and-expansion.html>

- The Guardian, “H&M: how does the fashion retailer’s sustainability report stack up?” April 24, 2013. <https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/h-and-m-sustainability-report>

- Grist: “Greening the clothing industry isn’t just about cotton and water. The message counts, too.” March 1, 2016. <http://grist.org/living/greening-the-clothing-industry-isnt-just-about-cotton-and-water-the-message-counts-too/>

- Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business (HBS Case)

- International Trade Center, “Cotton and climate change: Impact and options to mitigate and adopt” March 2011.

- H&M Conscious Actions Sustainability Report 2015

- EPA SmartWay <https://www.epa.gov/smartway>

- Quartz “If your clothes aren’t already made out of plastic, they will be” November 3, 2016. <http://qz.com/414223/if-your-clothes-arent-already-made-out-of-plastic-they-will-be/>

- The New York Times, “Science watch: The Nylon effect” February 26, 1991. <http://www.nytimes.com/1991/02/26/science/science-watch-the-nylon-effect.html>

- Forbes “Making Climate Change Fashionable – The Garment Industry Takes On Global Warming” December 3, 2015

“H&M has estimated that 10% of the CO2e emitted in a product’s lifestyle is a result of H&M’s retail operations. Another 36% comes from fabric production, and 26% come from caring for pieces at home.”

— Interesting LCA, but I wonder if this messaging is distracting us from the whole problem with fast fashion. The more fundamental problem with H&M is that they’re encouraging consumers to buy more clothing, more frequently. Seems as if, with their sustainability initiatives, they’re finding a local minimum.

Also, shameless plug for movement towards recycled materials. Patagonia uses recycled poly in its fleeces (though, technically really complicated and quite expensive), and chemically recycled cotton is closer and closer to commercialization. With H&M’s backing, could accelerate route to market.

There seems to exist significant evidence that the fast fashion industry poses a threat to sustainability, and companies such as H&M and Zara have crafted this idea of replenishing a wardrobe every season through affordability but also through abundance of new styles and garments every being released every season.

As more and more companies manufacturing products viewed as being “disposable” are being pressured towards sustainability, why is the fashion industry not in this discussion? People view single-serve coffee capsules as being a disaster from a sustainability standpoint, yet the fast fashion industry is shielded from such criticism. I do not want to take away from the importance of the different sustainability measures H&M is putting in place, but if the fast fashion industry is to remain the way it is, a garment recycling program, similar in concept to beer bottles, would be much more effective at addressing climate change.

Agree with your points Priya. This especially reminds me of the IKEA case where H&M as a leading, global retailer has the buying power to influence the supplier practices.

My concerns are echoed by the two comments above, which reiterate the point you make about fast fashion being antithetical to helping the environment given that the affordability increases waste. I think the starting benchmark should be H&M compared to other fast fashion companies first because if they’re not doing it then a perhaps less environmentally-conscious company is. The question is whether H&M or other fast fashion companies can innovate to find a way to make this practice sustainable (e.g., having consumers send back in clothing that can be recycled in some way), or if suppliers can move toward synthetic fabrics that have less of an adverse impact on climate change.

Thank you for your post Priya. To sko’s comment above, I wonder why you didn’t mention H&M’s program called “Long Live Fashion”, that offers customers a discount in their final purchases if they bring in old clothes (http://www.hm.com/us/garment-collecting). They accept any brand of clothing at any condition, which I find very convenient. I am sure that, although they still encourage people to frequently replenish their wardrobe with new clothes, they are also partially compensating this by recycling their customer’s old clothes.

I really enjoyed your post — very thoughtful and well articulated. I agree with much of what has been said in the prior comments, but one thing still remains unclear to me: how does H&M benefit from reducing their carbon footprint? Many of your points seem to suggest that it’s not in H&M’s best interest to move towards organic cotton and reduce the use of synthetic materials; adopting these practices would drive up costs and may receive push back from shareholders.

At the beginning of your post, you state that fast fashion retailers are being criticized for their unsustainable practices. I would have loved if there was more of a conversation about this and how H&M’s sales would struggle as a result of continued unsustainable practices. If sustainability practices would increased sales, then I could understand the business case for investing in eco-friendly business practice. I think this would also give additional credence to your closing sentence.

Great post, Priya! Some of the commentators suggest clothing recycling. In fact, H&M has been pushing clothing recycling for over 3 years now. In 2013, they launched their worldwide “garment collecting initiative” where you can drop of any garments, not just from H&M, in any H&M store and they will recycle it for you. I think this is an incredible and noble strategy, but I also know from our Marketing class that consumer behavior is extremely difficult to change. I wonder how many H&M customers are actually taking them up on this garment collection initiative. There may need to be some sort of incentive for customers, like a 10% discount off their next purchase if they recycle their clothes, to actually get them to participate.

Very interesting piece. You’ve made some good suggestions on how H&M can reduce their environmental impact without adversely affecting their huge business. My concern is that I do not foresee consumers not wanting the “fast fashion” concept. In that vein, one point you didn’t mention, is H&M’s new program that allows customers to bring in old garments for H&M to recycle in exchange for a discount on new purchases. In my mind, this kind of educational program that gives a tangible benefit to the consumer will be more effective in educating consumers/driving excitement about the H&M brand than any other effort.

Thanks for the interesting case Priya. Many of the posts above highlight the clothing recycling problem as an important step in the right direction, but I echo Kelly’s sentiment. Consumer behavior really needs to shift massively in order for the fast fashion retailers to truly make any step-change differences in their business model. H&M may source more organic cotton or even reduce its reliance on synthetic materials, but it’s ultimately the fundamental business model that creates tension with sustainability. Livia Firth of Eco Age argued that if fast fashion retailers still produce “in such volumes and at such ridiculous prices, their sustainability efforts – no matter how genuine – are a form of greenwashing.” One complicating factor this introduces, though, is whether you can effectively place blame on consumer segments that are ultimately very price sensitive and may not be able to afford sustainable clothing at a premium price.

Thanks Priya! Many prior comments referenced clothing recycling efforts and the need to change consumer consumption behavior. While some have applauded H&M’s recycling program, I don’t believe it does anything to fix the broader issue of sustainability and it negatively impacts local textile markets. The clothes that H&M collects are not actually recycled into new products; H&M is not creating a true closed loop system. Only 1% of the clothing that is collected can be recycled. (Something that is not told to the customers!) Daniel mentioned it above, but it does make H&M’s program appear “greenwashed” for the purposes of appearing focused on sustainability, and it makes customers “feel good” about donating. Secondly, more than 70% of the clothes donated globally end up in Africa according to Oxfam. Local textile manufacturers are unable to compete with these “cheap imports” from abroad, resulting in a collapse of the local textile industries and the corresponding jobs. Many countries were considering banning the import of second-hand clothes because of the negative impact to local economies.

Yes, H&M’s program keeps clothes out of landfills, but its business model remains in tension with sustainability unless it can focus its efforts on creating innovative recycling capabilities. For anyone interested, I recommend watching the documentary “The True Cost” http://truecostmovie.com/