The Facebook Flu: How Social Media is Changing Disease Outbreak Monitoring

Annoyed by your Facebook friends constantly complaining about their flu symptoms? Don’t be! They are an important data source for your local public health service’s disease monitoring system.

As Jon Snow so often reminds us, “winter is coming.” And with it comes increased precipitation, freezing temperatures, and millions of your friends’ Facebook and Twitter posts complaining about their cold and flu symptoms. Although these posts are not particularly newsworthy, they are beloved by health-savvy technology companies, academic institutions, and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

For decades, population health statistics across America were generated by the analysis of data gathered via periodic reports submitted by doctors’ offices, hospitals and public health departments. This information was used to inform and better prepare public health workers across the country for the coughing, sneezing masses they serve. Unfortunately, this data was often outdated by two-weeks by the time it was finally delivered to interested parties.

Thanks to the wonders of social media, the CDC and disease-loving research institutions like Johns Hopkins have been using your tweets to gather real-time information about population health. In fact, rather than just tracking existing outbreaks, they are now looking to use time and geographically-stamped tweets to better predict where and when illness will occur. This advanced warning could enable hospitals, schools, pharmacies and local community centers to better prepare themselves with additional antibiotics, medical supplies, patient beds, and optimize nurse and doctor schedules.

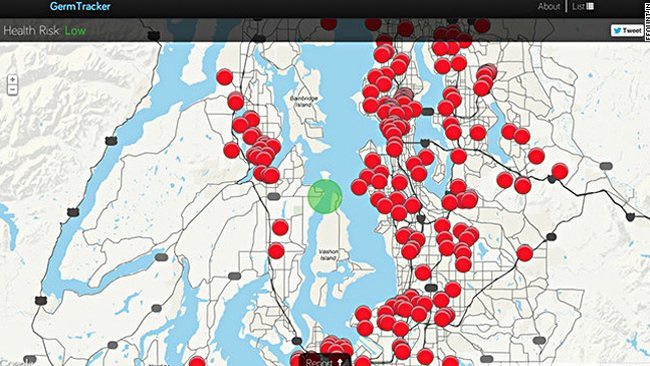

Over the past several years, many public, nonprofit and private groups have put great effort into tracking both common illnesses and rare infectious diseases. In 2011, a team of epidemiologists from the University of Iowa proved Twitter’s public health value by correctly tracking the 2009 swine flu (Influenza A H1N1) outbreak levels and public concern through simple key words. Other research groups have created web applications like Germ Tracker (pictured below) and Sick Weather that pull data from multiple social media sites and use real-time analytics to display colorful, animated maps that track health problems ranging from allergies to chicken pox to depression.

In 2009, Google partnered with the CDC to develop Google’s Flu Trends, which used anonymized flu-symptoms and remedy-related Google searches to better map and track worldwide disease outbreaks. The internet giant also developed Google Dengue Trends in an attempt to track the global path of Dengue fever. Although Google no longer actively supports these applications, it has made its historical estimates publicly available and is actively seeking academic research partners to explore this area further.

The CDC has also released a downloadable mobile phone app called FluView (pictured below) where users can see current data on the number of flu-like illnesses per state. While this application only provides basic, high-level data, CDC epidemiologists are interested in predicting even more detailed disease information. The ability to find detailed predictive information regarding outbreak severity, timing and strain type is particularly key in understanding if and how vaccines must be altered to work effectively.

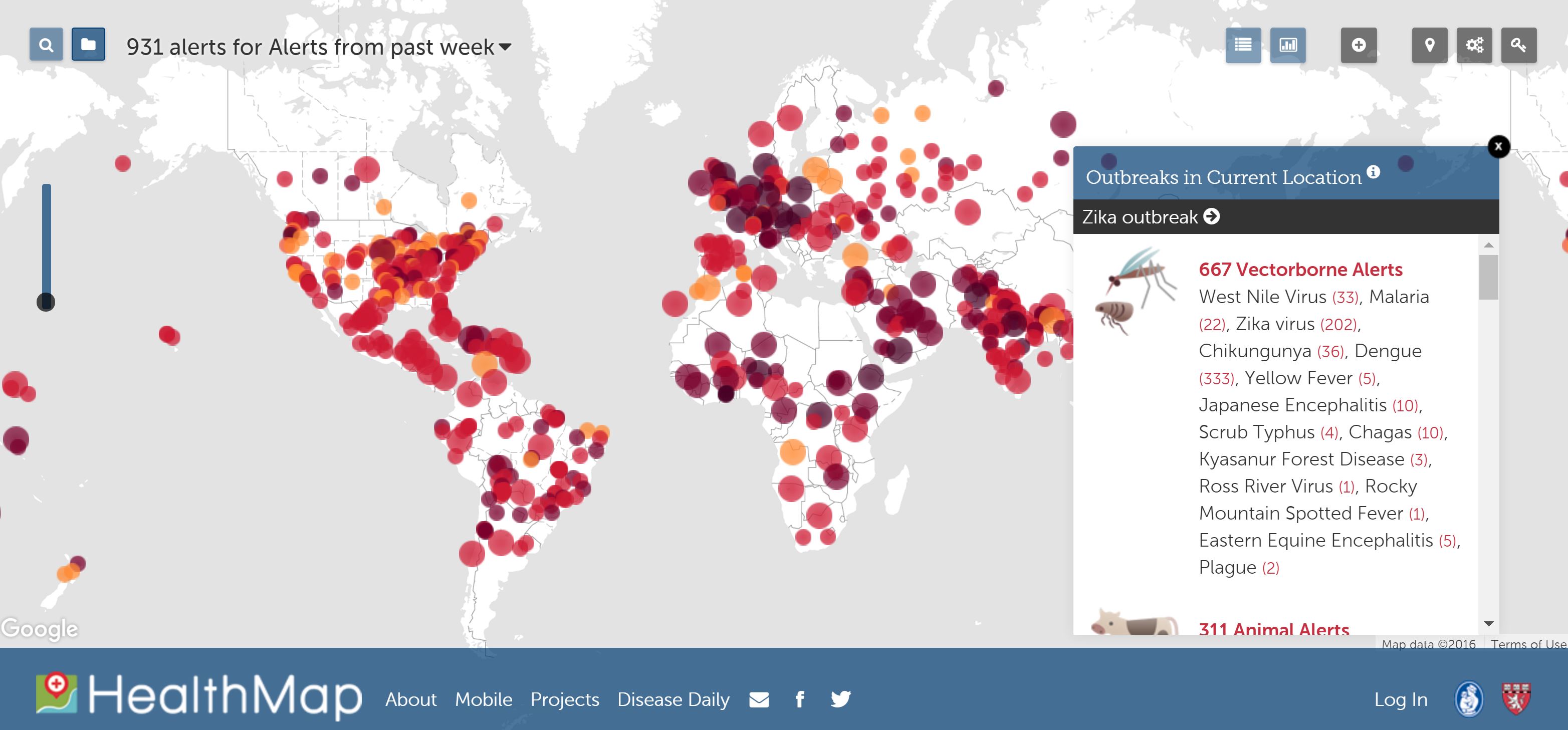

In fact, social media data may be key in informing the public and health response teams about both local and global disease outbreaks. Initiated a decade ago by a team of researchers and developers at Boston Children’s Hospital, HealthMap (pictured below) is a leading web and mobile app that monitors disease outbreaks by combining social media data with other authoritative news and health information sources. HealthMap mines, integrates and analyzes data from social media networks, eyewitness reports, official health agencies (e.g., World Health Organization, World Organization for Animal Health), online news sources (e.g., Google News, SOSO Info), and communicable disease surveillance (e.g., EuroSurveillance). In fact, HealthMap was able to report the recent Ebola epidemic 9 days before any public statement from the World Health Organization.

Although it may appear seamless, this data integration and analysis does not come without inherent limitations and systemic challenges. Because many Twitter postings rely on reactions to current news, perfecting algorithms to better separate meaningful disease indicators from related but insignificant noise (e.g., tweets commenting on a national flu outbreak) continues to be problematic. Additionally, since scientists often only trust verified, authoritative data sources, convincing public health researchers and government official of the value of nonscientific, unverified social media data remains a challenge.

In recent years, public health organizations have become more comfortable with using social media platforms to disseminate information widely and immediately, but an effective, direct information flow from the public to these agencies is still in its infancy. Overall, I would encourage organizations like the CDC to work more closely with technologically advanced and innovative academic and private partners to improve data aggregation and real-time analysis. Although there may be challenges around the sharing of unpublished population health data, an 86% baseline correlation between weekly flu tweets and national flu data is too significant to ignore.

(798 words)

Sources:

[1] http://www.cnn.com/2013/01/30/tech/social-media/flu-tracking-twitter/

[2] http://www.emergencymgmt.com/health/Social-Media-Data-Identify-Outbreaks.html

[3] http://www.bbc.com/news/business-29617831

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3087759/

[5] https://www.google.org/flutrends/about/

[6] http://www.emergencymgmt.com/health/Social-Media-Data-Identify-Outbreaks.html

[7] http://www.healthmap.org/site/about

Image Sources (in order of appearance):

http://machinelearningsoftware.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/353329-germtracker1.jpg

https://www.komando.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/11/fluview-app.jpg

http://www.healthmap.org/site/about

I had no idea all these apps and websites existed! They are going to become part of my winter flu watch…As a governmental agency, you don’t usually think of the CDC as on the cutting edge of social media technology. But from a quick browse through their website, it looks like they are actually very active online with a large number of digital resources (https://www.cdc.gov/socialmedia/). I wonder if this is a push to reach a younger, more news-conscious audience who prefers information pushed directly (and conveniently) to them. The use of social media for data analysis also poses many interesting questions. There is no doubt that mining tweets and Facebook posts can reveal a huge amount of real-time data on current trends in healthcare, but I wonder if this goes a step too far. What are the privacy concerns with analyzing even anonymous Google searches, Facebook status updates, and tweets? It’s an interesting balance between mining valuable data and encroaching on a (maybe yet undefined) social media line.

Thank you very much for the very practical post! While I totally agree with what Ariana mentioned about privacies, these SNSs are now playing very important roles in case of emergency. In addition to flu, for example in Japan, it helped many people when earthquakes occur. In 2011’s East Japan earthquake, as this telegraph’s article(link: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/twitter/8379101/Japan-earthquake-how-Twitter-and-Facebook-helped.html) says, many of mobile phone was not working at all, but people could communicate or know the situation of people real time. In this year’s Kumamoto earthquake, Facebook developed a service with which users in disasters area can declare their situations and their friends can see their situations real time. Though there are incremental anxieties about privacies, facebook is now becoming a lifeline tool.

This is super cool, thanks Alexandra!

Beyond just predicting, a lot of these are instrumental in also ending/preventing further spread of disease. Ebola is a great case of this.

Interestingly and slightly tangential, some pharma companies have started to experiment with social media to help them determine side effects not necessarily reported in clinical trials. This is significant because clinical trials are often highly controlled and only patients with few co-morbidities are included. Once drugs hit a larger market, unexpected things can happen. Further, it can be helpful to pharma companies to understand which side effects patients care most about. E.g. fatigue may not be considered a terrible side-effect in medical terms, but patients might strongly disagree. In a next evolution of the drug, a pharma company can use that information to cater to patients’ wants.