The Doctor will Skype you now — The Digitalization of Medicine

Partners Healthcare, one of the pre-eminent US hospital systems, has started to use TeleHealth to ease access issues, improve efficiency and extend reach in the healthcare field. But what are the longer-term risks of this trend?

Healthcare is often the last industry to be disrupted by a new innovation. While digitalization and globalization have touched almost everything we do, our model for healthcare delivery is quaintly old-fashioned. Information often flows using paper and service delivery is almost always local.

However, with improvements in TeleHealth – including remote monitoring technologies and secure video-conferencing — there are now significant parts of the healthcare supply chain that can delivered remotely. De-linking healthcare delivery from physical location has significant implications, both for quality of care (e.g., keeping people out of hospital) and efficiency. This is both an opportunity for, and a threat to, existing provider systems like Partners Healthcare.

Today: TeleHealth as a solution to access issues

The healthcare industry has embraced TeleHealth as a solution to a pressing problem – the delivery of health services in rural areas. 20% of the US population lives in a rural area, but only 9% of the nation’s doctors practice there [1]. For example, Nantucket Cottage Hospital is a Partners-owned hospital on Nantucket Island, a small island located 30 miles off the coast of Massachusetts [2]. Nantucket is a popular vacation spot, but has a population of only 10,000 for most of the year. Peaks and troughs in hospital occupancy make staffing a challenge, along with the difficulty of recruiting physicians to a remote location year-round [3]. This results in significant transport costs associated with supply of medical treatment for those on the island. TeleHealth has eased that burden in specialties like dermatology where information is shared visually.

Tomorrow: TeleHealth to match supply with demand

Thirty years ago your local pharmacy competed with the pharmacy across town. If there was only one, you probably paid a higher price for it. Now you can go on Amazon or Walmart, compare prices and have an item shipped across the country. Regional players can no longer extract margin for simply being present. Today, when a company looks for a call center location, they may entertain bids from Costa Rica, India and Romania.

But pricing in healthcare is still based on very local competitive dynamics — How big are you? How many other hospitals are there nearby? For many provider systems, the answer to these questions are big, and not many [4].

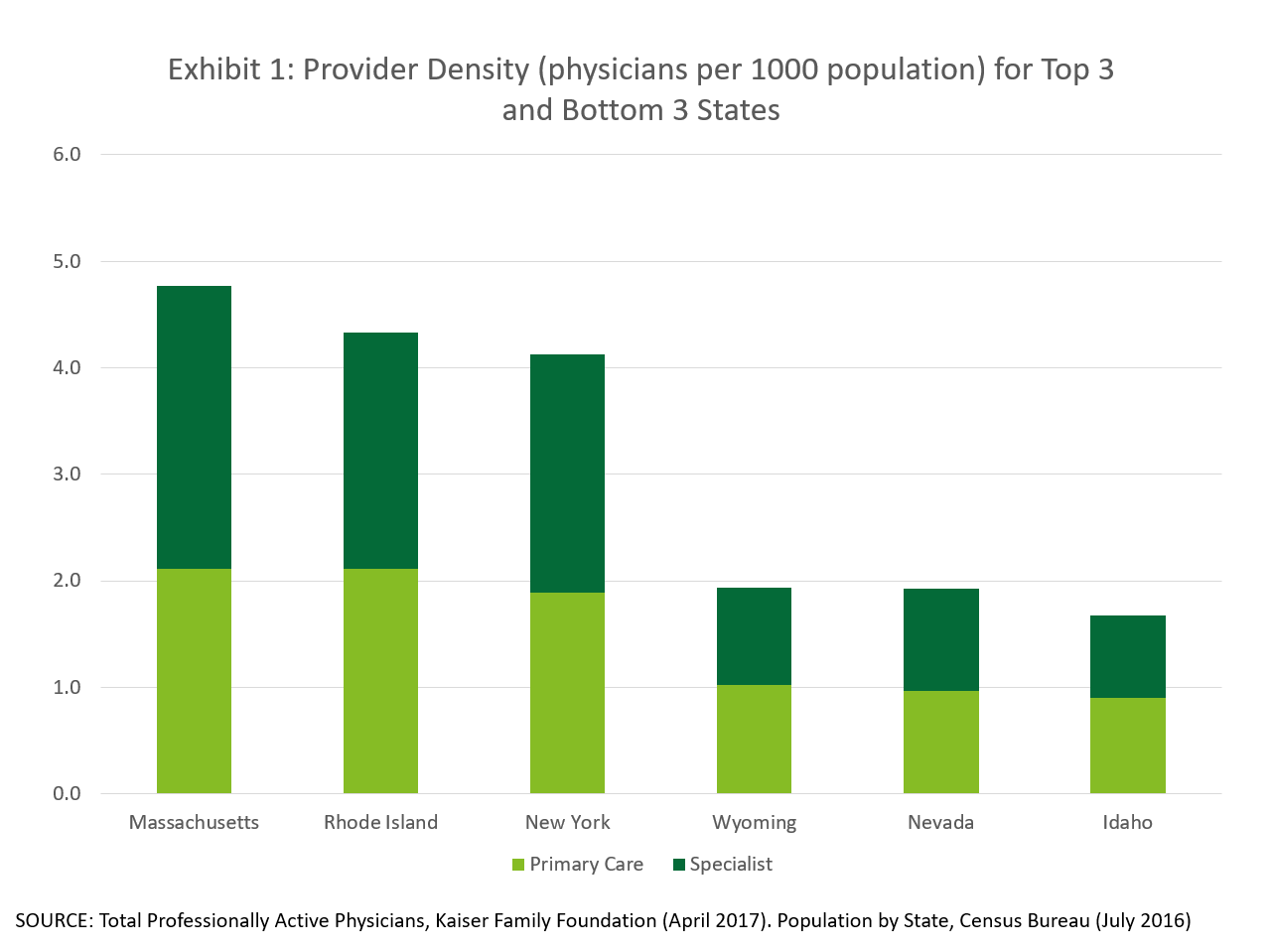

There are also large supply-demand imbalances within the US. Exhibit 1 shows that there is a 2.5x difference in physician density between the highest and lowest density states [Chart created from data sources 5 & 6]. Because the supply of healthcare is local, the market cannot clear efficiently.

In a world where healthcare can be delivered remotely localized supply/demand imbalances should normalize. This presents an opportunity for Partners – to expand its reach outside Massachusetts – and a potential risk – of additional competition from provider systems outside the State.

So far, Partners is taking advantage of the opportunity. In 2011, it launched a broader TeleHealth initiative and has conducted over 20,000 virtual visits [7,8]. Partners is also using TeleHealth to reduce the need to transport patients between facilities. These growing initiatives will improve its cost position and will help it stay competitive. Partners is also using the technology to increase national access to high-quality specialists, through offering e-consults for second opinions to patients outside Massachusetts. Both these uses are growing and there is growing interest from practices within Partners Healthcare to join TeleHealth programs.

Eventually: TeleHealth as an outsourced service?

But remember… the US has double the healthcare spending per capita of the average developed nation [10]. Much of this is driven by high physician compensation, which is also approximately double the average of other developed nations [11]. When the contrast is drawn to emerging markets, the difference becomes even starker.

Medical tourism (a.k.a. outsourcing) has existed historically for expensive procedures that can be achieved at significant discounts outside the US without compromising quality. Companies and health plans are increasingly reimbursing these procedures carried out abroad. But why constrain ourselves for high cost procedures? Why not use highly qualified medical teams in low cost hubs to conduct medical triaging, primary care visits and behavioral health consults?

What’s next for Partners Healthcare?

Partners could choose to either fight the trend (e.g., by lobbying to maintain regulations on state and foreign licensures) or embrace it. Partners could leverage its stellar reputation to support global connectivity in state and federal legislatures, expand use of remote monitoring technologies and extend its services across the US and beyond. Getting ahead of this trend could establish Partners Healthcare not only as a pre-eminent Massachusetts institution, but a global one.

Many questions remain – for Partners and for everyone in healthcare. Eighteen percent of GDP is tied up in healthcare services, largely in wages [12]. How does a high-wage country like the US compete in a global market? Will healthcare workers be the next coal miners?

Word count = 799

References:

[1] Roger A. Rosenblatt and L. Gary Hart, “Physicians and Rural America,” Western Journal of Medicine 173, no. 5 (2000):348-51. Accessed November 2017.

[2] Pam Belluck, “With Telemedicine as a Bridge, No Hospital is an Island”. New York Times, October 8th 2012. Accessed November 2017.

[3] The Use of Telemedicine to Address Access and Physician Workforce Shortages. American Academy of Pediatrics. July 2015. Accessed November 2017.

[4] CC Havinghurst, “The Provider Monopoly Problem in Healthcare” Oregan Law Review Vol 89: 847. Accessed November 2017.

[5] Data excerpted from Total Professionally Active Physicians, April 2017. Kaiser Family Foundation data. Accessed November 2017.

[6] Data excerpted from Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States and Puerto Rico; April 1, 2010 to July 1 2016, US Census Bureau, Population division. Accessed November 2017.

[7] Adam Licurse, “One Hospital’s Experiments in Virtual Health Care”, Harvard Business Review, December 9th 2016. Accessed November 2017.

[8] Partners HealthCare continues Accountable Care Organization collaboration to deliver better care to Medicare patients. Press release, January 25th, 2017 on Partners Healthcare website, accessed November 2017

[9] Interview with Partners Healthcare Physician, November 15, 2017

[10] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD Health Statistics 2016, June 2016. Compiled by PGPF. Accessed via Peter G Peterson Foundation website. Accessed November 2017.

[11] Congressional Research Service analysis of Renumeration of Health professions, OECD Health Data 2006, accessed via New York Times, “How Much Do Doctors in Other Countries Make”, July 15 2009. Accessed November 2017.

[12] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, National Health Statistics Group at www.cms.hhs.gov/nationalhealthexpenddata, accessed November 2017

This is a very interesting topic, and I enjoyed reading your take on it! One area of medicine in which “outsourcing” has been established is teleradiology. In this field patient images recorded in one location, like x-rays and CT scans, are electronically transmitted to physicians in another location for reading and evaluation. Results are transmitted back to the ordering providers and appropriate next steps are taken for the patient. As you mentioned, a practice such as this is increasingly common in rural locations – physicians in Washington often read the scans of patients in Alaska. One particularly powerful takeaway from the uptake of this technology is seen in study turnaround times; one article I read on an Alaskan teleradiology project stated, “Teleradiology has greatly decreased the turnaround times for diagnostic interpretations from 9 to 21 days to within 24 hours and immediate response on emergencies” [1]. That’s an incredible improvement! And I think we can expect to see increased care delivery improvements as telehealth continues to expand. Interestingly, the growth of teleradiology has caused salaries to increase, instead of the opposite (as I would have expected) [2].

One concern I have heard both for teleradiology and telehealth as a whole regards outsourcing internationally. One the one hand, this would greatly reduce costs for the system. But on the other, there are concerns regarding malpractice accountability, as well as nonuniform quality standards (e.g. these physicians are not licensed or certified by US medical boards). As discussed in a relatively old New England Journal of Medicine article, I imagine that this will continue to be a hotly-debated and polarizing issue among the physician community in the United States [3].

[1] Chris Patricoski (2004) Alaska telemedicine: growth through collaboration, International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 63:4, 365-386, DOI: 10.3402/ijch.v63i4.17755.

[2] http://www.radiologybusiness.com/topics/healthcare-economics/3-radiology-takeaways-2017-physician-recruitment-report

[3] http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp058286#t=article

Excellent insights, thank you for covering such a critically important topic.

Healthcare lags behind other industries in terms of most technologies that do not directly address procedural care. While Telehealth promises to match supply/demand mismatch between patients and providers, the upfront capital expenditures required to install working systems, alongside the already onerous CAPEX hospitals have recently (for the most part) spent on upgrading EMRs, may prove too costly. This is complicated by the fact that matching supply and demand may, at least in the short term, unleash so much unmet demand that costs will skyrocket further past 18% GDP if provider systems cannot figure out how to capture value from these systems by decreasing costs (as opposed to serving more patients alone) – see this recent Health Affairs article from Ashwood et al. for good exegesis: https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1130. So far, it seems most value can be captured from these platforms in radiology (as above noted), dermatology (company profile: 3derm – https://www.3derm.com/) and mental health with promising new local startups like Valera (https://valerahealth.com/).

While large telehealth firms like Boston-based AmericanWell and provider groups have lobbied for improved interstate licensure and reimbursement of telehealth, its ultimate value add may be as a means of increasing touchpoints with patient in chronic disease management through capitated primary care systems that need more contact with a certain cadre of patients but less expensive visits.

Thanks for the article! My previous employer offered Telehealth services, though I never took advantage of it. Certainly, this technology and service can help patients in rural areas to get access to healthcare. But as you mentioned in the article, 80% of the US still lives in non-rural areas. I wonder how these services can attract patients to adopt Telehealth rather than drive to the doctor. I think it is possible, but it will take time. After all, we now get into cars with strangers and sleep in strangers’ homes.

I would also add that trust and verification is going to be critical in this space. What’s to stop a random person to just setup a website to deliver telehealth services via a staff of “doctors”. The brand of the company delivering this is going to be a critical piece in gaining patients’ trust to adopt this new delivery method of healthcare.

Thanks so much for the interesting article!

When I saw the title of this article, I was expecting to read about TeleHealth increasing access to healthcare in emerging markets, and found myself wondering (briefly, before I clicked through 🙂 ) if and how this was being used domestically. I was intrigued to read more about this challenge, and can see how salient of an issue it is in more remote locations. Nantucket was a very interesting example.

I completely agree with what Sharat brought up regarding concerns about trust and safety, and how quickly TeleHealth will achieve market diffusion in the U.S. as a result. Look forward to continuing to follow this topic!

Fascinating topic Alexia, thanks for the insight. It’s interesting that you raise the use of telehealth in order to service people in rural areas or areas that have a fluctuation in population density. I can absolutely see telehealth as having a much broader application – perhaps for people with chronic conditions that require regular (but often non-urgent) check-ups. I can also see a large demand for the service for patients that require psychological or counselling support. I think your idea of ‘outsourcing’ patient care to low cost-centers across the globe is particularly interesting. I wonder whether you could take this a step further and introduce an automated / digital triage system where the patient enters in their symptoms and is more directed to a lower-cost provider (nurse instead of doctor, or international doctor instead of US provider) for non-life threatening conditions?

Amazing article Alexia, I really enjoyed reading it. Although I know little about the mechanics of Telehealth, I wonder how can this technology be introduced in other countries where not only the skepticism exists in a stronger way, but also the technology is not there. For example, one way to deliver Telemedicine would be through computers or mobile phones, however how can this technology be levered to the people that need it the most in rural, isolated regions of poor countries? The amount of capital expenditures required is massive. I guess one way to do it is having your profitable, large scale operations in developed countries subsidize these actions.