Tata – Leading the way in dealing with Steel’s black sheep?

Who should take the lead advancing the response to climate change in the heavily polluting industry? Should it be community focused Tata Steel, who will risk pricing themselves out of a commoditised market, or majority producers China, who have not signed up to emissions goals?

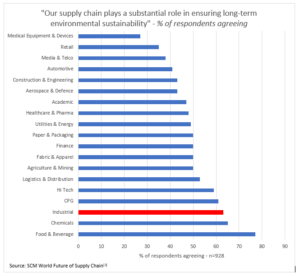

The Steel industry finds itself at a critical juncture in dealing with climate change: it is one of the world’s worst polluters [1], one of the most affected by its impacts as the major supplier of raw materials to the automotive industry, and one of the industries with the most substantial role in using its supply chain to ensure long-term environmental sustainability (Figure 1) [2]. Tata Group, renowned since its inception 150 years ago for its social responsibility to the communities within which it operates (and continuing to be owned by a charity) [3], now finds itself with a significant moral dilemma as it is forced to embrace the entire global family as its community, and lead other industries as a beacon of responsible management and conscientious improvement in the face of increased competition and reduced demand.

The use of energy in Steel production exceeds 6.5% of global CO2 emissions each year [4], with approximately 220kg of steel used per capita per year [5]. However, the hazardous emissions to air and water render it far more prominent in the global debate for climate than its CO2 emissions alone. Furthermore, it represents around 95% of all metals produced but has a geographic distribution based on proximity to inputs (iron ore and labour), placing over 50% of total production in China [6] thus causing large knock-on environmental effects down the supply chain once the responsibility has moved off the Steelmakers’ books.

At present, Tata’s major short term efforts to reduce the impact of the steelmaking supply chain revolve around recycling of steel – it cannot be consumed and remains the only truly cradle-to-cradle recycled material. However, contrary to the insinuations on the company website such as “not only fully recyclable, but […] actually recycled” [7], only about 41% of inputs to global steelmaking are from recycled sources today [8]. Academics estimate that 90% is theoretically possible [9], leaving the industry significant room for improvement; this will not be achieved without worldwide advancement toward policy-making – something which has been proven notoriously difficult in countries such as China.

Furthermore, Tata is currently working in the medium term to increase its proportion of electric arc furnaces. These use more steel scrap as a ferrous resource and less energy per ton than the current norm [9]. The major benefit of this is the theoretical move towards clean energy, where electrical input can be provided by clean sources such as wind or tidal energy – as opposed to the coal used in today’s blast furnaces. Many furnaces are currently located near coastlines for cooling (eg: Netherlands) where access to different forms of renewables will continue to improve.

Though many smaller tangential efforts can and should continue to be made to increase the proportion of recycled steel, supply chain managers can – and must – play “a major leadership role in addressing the alarming consequences of aberrant global weather conditions” [10]. Tata Steel should embrace its leadership position on the production side to advance two further solutions in response to the pressures it is under from climate change: committing to biofuels for industrial power, and increasing transportation efficiency with cooperative trade deals.

Biofuels have long been hailed as a potential solution to many energy requirements, however it is in industrial production where their greatest disadvantages (such as a lack of developed infrastructure in their supply chain to ensure adequate delivery to end automotive users) can be minimised, and thus their use maximised [11]. Areas of barren land such as the Taklamakan desert provide fertile ground for the production of algal biodiesel, while still being close to major infrastructure to access steel production facilities in China [12].

Transportation is another example of how Tata could pave the way in increasing collectively beneficial activities across different players in such a globally-competitive industry. Prices in the last years have fluctuated beyond analyst expectations due to Chinese investments, with the major opportunities relying on proximity and speed to delivery, rather than variable production volumes. This structure provides a niche for a cross-company platform to trade steel across continents depending on prices and availability on a shorter-term basis. Such a platform was developed to great success for ocean shipping capacity, and should be developed in Industrial Goods.

What remains for Tata and for the steel industry to opine and act on, is who should take the leadership in addressing some of the ongoing concerns mentioned above. Tata is in a position of responsibility for its commitment to community, yet does not produce the majority of global steel. In fact, that mantle falls on the shoulders of the Chinese: should Tata lead the way to improvements and risk cutting itself out of a commoditised market if the Chinese do not follow, or should it do whatever it can to remain competitive?

(Word count: 793)

Sources

- International Energy Agency statistics, http://www.iea.org/statistics/topics/CO2emissions/ , accessed November 2017

- SCM World Future of Supply Chain Survey 2015, SCM.com, accessed November 2017

- “Tata Sons: Passing the Baton”, Forbes India, http://www.forbesindia.com/printcontent/31052, accessed November 2017

- “Steel Production and Environmental Impact, data from IEA, http://www.greenspec.co.uk/ building-design/steel-products-and-environmental-impact/, accessed November 2017

- World Steel Association on environmental sustainability, https://www.worldsteel.org/steel-by-topic/sustainability/environmental-sustainability.html, accessed November 2017

- “World Steel Production by Country 2017”, World Steel Association, https://www.worldsteel.org/en/dam/jcr:44ae2d3d-62ff-4868-9f60-e17a43e75092/Crude+steel+production_March+2017.pdf, accessed November 2017

- “The sustainable material”, Tata external publication on company website, https://www.tatasteeleurope.com/en/sustainability/steel%E2%80%93for%E2%80%93a%E2%80%93sustainable%E2%80%93future/sustainable-material, accessed November 2017

- “Steel Production and Environmental Impact, data from IEA, http://www.greenspec.co.uk/ building-design/steel-products-and-environmental-impact/, accessed November 2017

- “The impact of climate targets on future steel production”, scientific paper produced by Elsevier, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652614004004, accessed November 2017

- “Supply Chain Leaders Urged to Embrace Climate Change Solutions”, Logistics Management website, http://www.logisticsmgmt.com/article/supply_chain_leaders_urged_to_embrace_climate_change_solutions, accessed November 2017

- “Growing a sustainable biofuels industry: economics, environmental considerations, and the role of the Conservation Reserve Program”, Scientific journal, http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/025016 , accessed November 2017

- “Rheology of Algae for the production of biodiesel”, Chemical Eng. Dept. Univ. of Cambridge, UK

Great post Nico! This was fascinating, I had no idea that the steel industry contributed so much to annual global emissions.

Steel production is a fundamental commodity in today’s world, and I’m curious about a “network affect” that might occur if the price of Steel goes up. What if an alternative becomes popular that has not taken on the costs of reducing their emissions? How does Tata differentiate itself in a world where the steel used is largely invisible to the end consumer? Is there a way for a commodity to be environmentally conscience while also being profitable?

Nico, Tata’s socially responsible behavior seems to be well timed with changing global trends. After driving down global steel prices through surplus production, China seems to be the key player in increasing the very same prices [link 1 below]. More encouragingly, this has partly resulted through pressure from environmental agencies [link 2 below]. This interplay of supply and prices has resulted in a second favorable trend – shift towards recycling scrap steel vs. using iron ore for manufacturing new steel in China – which is likely to be further enhanced by 2020 [link 3 below]. Tata Steel may not have caused these changes in the Chinese steel industry, but the changes are consistent with Tata’s mission towards the global community and environment. So, while neither the Tata-led Indian steel industry, nor its bigger sized counterpart in China is de facto leading this environment friendly push, positive signs seem to be on the horizon.

[1] http://www.livemint.com/Money/82EpmoCxx6TNxAXlWagr9K/Tata-Steels-outlook-pinned-on-Chinas-appetite-for-steel.html

[2] https://www.ft.com/content/df5b1478-a1df-11e7-9e4f-7f5e6a7c98a2

[3] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-steel/getting-scrappy-china-iron-ore-demand-may-falter-as-steel-recycling-grows-idUSKBN19Q0U3

Glad to read this Japees, thank you for sharing!

Hi Nico – Great article! I totally agree with your analysis that resonates with me in many other sectors. We live in a world that works at different speeds, with developed countries and industries that are trying to embark in a more “risk-environment” friendly production vs. developing countries that are mainly focused in growing as much as possible their stakes. Based on this, do you think that is Tata responsibility to move forward and be the pioneer of this environmental revolution, with all the risks you mentioned, or should governments and supra-national organization take the lead? In other words, do you think Tata should act as a first mover and force competitors to follow its approach or should Tata lobby supra-national organization to impose more stringent regulations on CO2 emissions in the steel industry?

This is a really interesting article, Nico. I worked in India in the same city where TATA steel headquarters are based and had close friends working at TATA steel who told me about a conscious and deliberate shift in Tata’s strategy to invest in technological improvements in cutting down carbon emissions. Just to give some context, in the recent decade, the Indian government has given guidelines to large corporates to focus on “Triple Bottom Line” in performance which includes financial, social and environment impact performance. This along with the growing awareness in consumers and the market has given impetus to many CSR and environment oriented initiatives by large market cap firms.

Tata Group is certainly making the right strides in this direction and recently purchases a smelter technology from Rio Tinto which is intended to reduce carbon emissions by at least 20 % [link below]. To the broader risk of cutting out of a commoditized market, I feel one way that commodity manufacturers can approach this issue is by lobbying with the government to create strong barriers to entry in the market based on environmental impact and emissions. This will not be a hard sell given the government’s current focus and they can agree to restrict the market to only those players whose emission levels are a certain threshold for example. This will drive the competition to follow suit and invest in environmental friendly technology. Given TATA steel’s investment might and influence, it might be a good strategy to invest and develop clean technology and dictate the trends in the market through government interventions.

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/tata-steel-acquires-rio-tinto-smelter-tech-to-cut-cost-emission/article9901134.ece