Recreating the Harvard Book Store

The digital onslaught of e-books and Amazon-style e-tailers have put bookstores in an existential predicament. –The Economist, 2013 [1].

Situating the industry

It is obvious, and anything but surprising, that the rise of the digital age and the increasing use of technology is wiping out certain businesses, book stores being one of many. By the end of 2011, a survey found that 43% of Americans over 16 read long-form content, defined as books, newspaper articles, and magazines, in digital format [2]. The continued rise in e-books and the expansion of e-tailers like Amazon lead to the down-sizing and closure of many large bookstore chains, most famously, Borders [3,4]. As a previous Borders’ manager puts it, “A comet killed the dinosaurs. I’m afraid the internet is that comet and Borders is one of those dinosaurs” [4].

Harvard Book Store

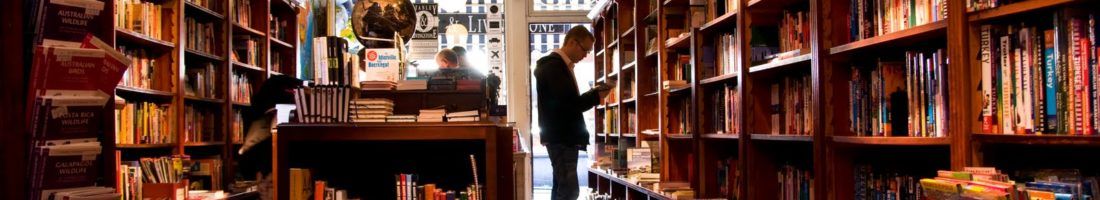

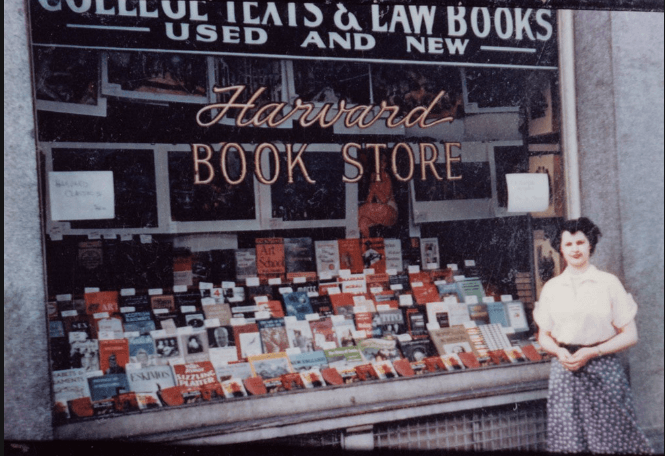

Stepping away from industry trends and the big picture for a second, we know that mega-chain book stores are taking a hit because of digitization, but what about the small players? Over the Charles, in our own backyard, the Harvard Book Store stands [see image below, 5]. The store has been in operation since 1932 and has become a landmark in Cambridge [6] with thousands of tourists, students, and locals flocking in weekly. Since its opening, the book store has always been independently owned and in 2008, the book store was sold to Jeff Mayersohn. Mayersohn, a book lover and retiree of the tech world, understood the magnitude of his responsibility in ensuring the continued success of the Harvard Book Store.

The problem

In the US, e-book sales have been increasing at double digit rates while sales of printed books were falling [7]. Mayersohn saw the trend first hand in the store he had bought. He recounts seeing customers come into the shop, spend some time browsing, find a nice corner to get comfortable, and spend some time reading. If they liked the book, they would proceed to pull out their smart phones and order the book online [8]. Having access to the universe’s entire library with a few clicks on a smart phone or a download on an e-reader was too convenient. People often came to the store, but no one thought of it as a shop anymore; it was now a place to relax and read.

Brainstorming

Mayersohn theorized that customers liked the digital libraries, Amazon, e-books, etc. for a few key reasons: unlimited options, instant gratification, and a dependable delivery system. Studies looking to understand the massive rise in the use of digital libraries and electronic reading devices supported his theory [9]. He decided to try to get the Harvard Book Store to fulfill the aforementioned customer expectation. What if the book store could provide access to every book ever published? Was there a way to produce, deliver, and distribute content at the same rate as the digital versions?

When creativity meets technology

The answer was, yes. Mayersohn used his background in technology to completely transform the business model. He decided to install an Espresso Book Machine (EBM), a device that prints any book from the public domain in minutes [10, see image below 11]. With libraries increasingly converting their titles into e-format and adding them to digital libraries, more and more titles found themselves in the public domain. This meant the EBM’s catalogue was growing, at no cost to the book store. Additionally, the EBM could also print custom publications meaning patrons of the store could get their own works published, serving as an additional revenue source. This one machine allowed the customer expectation for more book options and instant gratification to be met. In fact, the machine redefines “instant” as it is faster than purchasing a book online. Operationally, it decreased the inventory that had to be carried, saving costs, and customers were able to get their hands on any book they desired, even hard-to-find or out-of-print titles.

To further make use of the EBM and implement an e-tailer model that was now mainstream, the book store’s website was overhauled to allow online orders. Mayersohn added guaranteed same-day delivery for customers living in the Cambridge/Allston area. This allowed him to achieve the third customer expectation of reliable delivery. Realizing how technology could boost his business, Mayersohn leveraged social media. He used it to market the EBM, reeling in new customers and maintaining engagement with current ones. He also used the platform to drive people to the brick-and-mortar store by advertising superior customer service provided by passionate booklovers.

In conclusion, the Harvard Book Shop serves as an incredible example of how technology was able to revive a dying business. Mayersohn realized that people fundamentally preferred the easy, click-of-a-button option, but many still valued the experience of browsing, spending time in, or visiting a book store. He was able to merge the two desires by allowing patrons to walk that path of least resistance in a physical location.

(Word count: 800)

[1] “The real cliffhanger.” The Economist. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2013/02/future-bookstore>.

[2] Raine, Lee et al. “The rise of e-reading.” Pew Research Center. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://libraries.pewinternet.org/2012/04/04/the-rise-of-e-reading/>.

[3] Borders Group. New York Southern Bankruptcy Court. Accessed Nov. 2016. <https://www.pacermonitor.com/view/NSNXPWY/Borders_Group__nysbke-11-10614__0001.0.pdf>

[4] Bomey, Nathan. “Ann Arbor bookstore chain files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.” The Ann Arbor News. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://www.annarbor.com/business-review/borders-bankruptcy-ann-arbor-books/>.

[5] The Harvard Bookstore. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://www.harvard.com/about/history/>.

[6] The Harvard Bookstore. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://www.harvard.com/about/hbs_in_brief/>.

[7] McNeil, Sophie. “Five Key Trends in the Book Market.” Penguin Random House. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://authornews.penguinrandomhouse.com/five-key-book-market-trends/>.

[8] Johnson, Phil. “The Man Who Took on Amazon and Saved a Bookstore.” Forbes. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://www.forbes.com/sites/philjohnson/2012/05/10/the-man-who-took-on-amazon-and-saved-a-bookstore/#305bab2b4204>.

[9] Tveit, Ase K. et al. “A joker in the class: Teenage readers’ attitudes and preferences to reading on different devices.” Library and Information Research. Accessed Nov. 2016 from Elsevier. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740818814000516>.

[10] “Overview of the Espresso Book Machine.” On Demand Books. Accessed Nov. 2016. <http://ondemandbooks.com/ebm_overview.php>.

[11] Image. Accessed Nov. 2016. <https://laughingsquid.com/wp-content/uploads/6256317164_b132e2154c_b.jpg>.

Interesting post about something in our own backyard! I wonder, though, if one of the reasons for the rise in digital books and ordering from Amazon is the ease of having the book readily on your device (e.g., Kindle, iPad). Now, consumers to not have to lug around heavy books with them. If this can explain some of the rise in digitalization, then the EBM will not solve the fundamental problem of customers still going online to buy their books.

Great post- the Espresso concept is very interesting. I’d like to see a player that does the opposite by allowing you to trade in physical copies of books for digital versions. Vudu, a company now owned by Walmart, essentially provides this service by converting DVDs to digital copies for a nominal fee.

The great drawback of a digital copy is you almost always have to pay full price and the book has zero resale value. There would also be value in somehow creating a secondary market for digital books, although I think that is prohibited now based on licensing. Maybe over time as the market matures we’ll see the ability to trade digital copies.

Really interesting post! I think the unique value of the Espresso Book Machine – to Harvard Bookstore patrons, at least – might be the ability to print a book not otherwise available in hard copy format via Amazon or other online retailers. If Mayersohn can ensure and emphasize this capability then he might provide valuable differentiation that keeps his machine from competing directly with the e-book providers that have decimated brick and mortar bookstores.

The Harvard bookstore seems to have found a creative mitigation of an industry wide issue in EBM. Whether it offsets the main problem of declining book sales remains to be seen. EBM seems to be a source of adding another revenue stream but I wonder whether the incremental impact has been substantial. Several questions that come to my mind are:

1. How many people have used EBM? Have consumers embraced this new technology or is there reluctance in usage? 2. Is there a difference in the new technology adoption pattern between the academic community vs. general public?

3. How many e-prints of public domain book collections have been done vs. own custom publications?

4. Has there been a net incremental positive impact on the Harvard Book store revenue?

One the positive side, EBM supports a creative and intellectual community by giving anyone the opportunity to independently publish their work for a nominal cost creating a stronger market for niche publications. It is an efficient way to manage supply chain cutting inventory holding and distribution costs. Having an espresso book machine also positively influences library collections by supporting a somewhat patron-driven acquisition model. By giving the users the ability to print and request what they want instead of having library staff predict, sometimes erroneously, avoids large unused physical collections taking up spaces within the library.

There are some limitations that may need to be evaluated such as the high price, requirements of warming up the machine for an hour before printing, restrictions with publishers to print new titles, and interface quality for the machine’s database of printable titles. These limitations may be insurmountable for smaller book stores who may still have to go out of business. If EBM evolves to become mainstream the net benefits would have be weighed with its limitations to see whether its worthwhile to make heavy investments.

I found the below EBM study particularly interesting to read specifically the demarcation between the Long tail theory and the Pareto principle both of which talk about influences on technology diffusion with reference to EBM.

http://www.windsorpubliclibrary.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2015/04/here..pdf

Thanks for this Orianne. I have a few thoughts. Firstly, given the expense of paying rent in a prime location, which a book store needs to do, how can this machine help The Harvard Book Store compete on price? Surely, an online retailer can have equivalent inventory costs by having a similar machine in a cheaper location and print books as they receive the orders. Secondly, if a consumer knows what they want, more often than not they don’t need to go to a book store to get it printed, they can just order on line. This machine will surely only capture consumers who know what book they want? If they didn’t they would have to browse the shelves of the book store and make a purchase based on a book they came across and liked i.e. they would not need the help of the EBM.

Finally, how can you monetise, “the experience of browsing, spending time in, or visiting a book store” – it is free at the point of consumption to the consumer but not to the bookstore.