Not in your Size? Not a Problem

3D knit printing has the potential to disrupt the retail clothing industry, and Ministry of Supply is leading out in front.

Ever fall in love with a shirt or dress while out shopping only to find it didn’t fit right or wasn’t in your size? Ministry of Supply is leaping into the future to change that. A 50-foot crane was used to lower a massive 3000 pound machine made by Shima Sheiki into Ministry of Supply’s Newbury Street store[1]. That machine, costing a hefty $160,000, is capable of printing a personalized garment of clothing in under 30 minutes[2]. Paired with computer-aided design software, Ministry of Supply currently offers customers fully customized blazers printed right in the store, as well as a number of other 3D printed knits online.

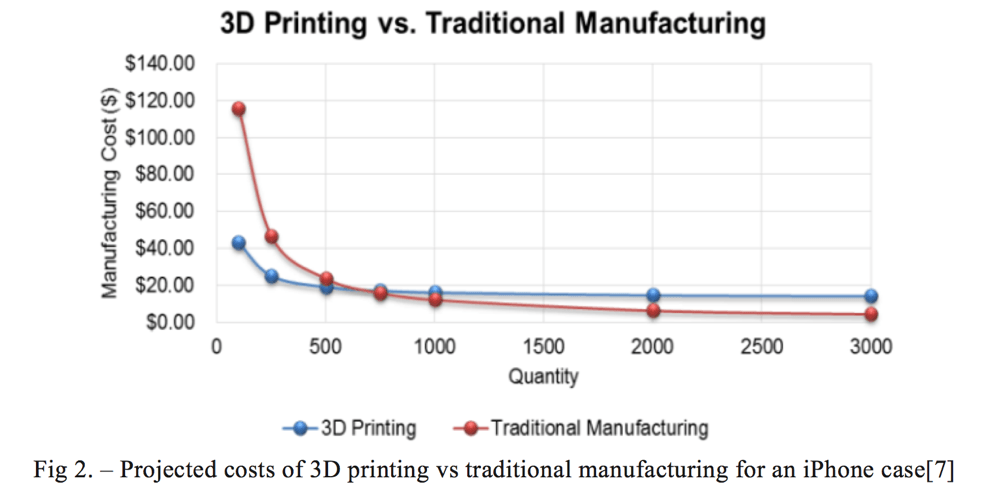

Ministry of Supply is operating at the cutting edge of textile manufacture and design as one of the first clothing retailers to utilize a 3D printer in-house. While it may sound a bit gimmicky at first glance, 3D printed textiles have the potential to completely uproot the retail clothing industry. The digitization of designs combined with the in-house manufacturing that 3D printing enables may one day allow Ministry of Supply to completely eliminate a huge portion of their supply chain, going from the multi-staged approach pictured on the left (Fig. 1) to the drastically shortened supply chain on the right – or even shorter if a customer visits the store themselves, which would eliminate the need for distribution and delivery as well[3].

However, eliminating such a large portion of the supply chain could have major consequences. 3D printing’s largest consumer-facing front has been through inexpensive desktop printers that can print anything from a bottle opener to a functional firearm. With the rise of these desktop printers, online marketplaces and exchanges such as Shapeways and Thingiverse cropped up, allowing anyone to share and download designs around the world. This sharing and exchange of designs has resulted in copyright claims and illegal use of online designs, not dissimilar to pirating movies and music[4]. Furthermore, 3D printing fab shops have also emerged, allowing anyone without their own printer to bring in a design of their choosing and have it created for them[5]. One can imagine a not-too-distant future where these concepts are applied to 3D printed textiles, with fab shops allowing customers to create personalized clothing using online designs and clothing design software as ubiquitous as Photoshop. This would drastically lower the barrier to entry for clothing designers and could give rise to an entirely new competitive landscape for traditional clothing retailers.

Fortunately for Ministry of Supply, they’re far ahead of the curve. In addition to offering 3D printed items produced at their production facilities, Ministry of Supply prints customized knitted 3D printed blazers for $345 at their Newbury store, making them one of the first retailers to utilize point-of-sale 3D printing in their stores1. They are rapidly learning from the use of their printers and plan to expand the use of 3D printing in their production facilities, aiming to produce up to a quarter or even a third of their supply via 3D printing within the next few years[6]. Ministry of Supply recognizes 3D printing’s ability to provide a personalized experience to their customers and CEO Aman Advani will likely continue to push the envelope.

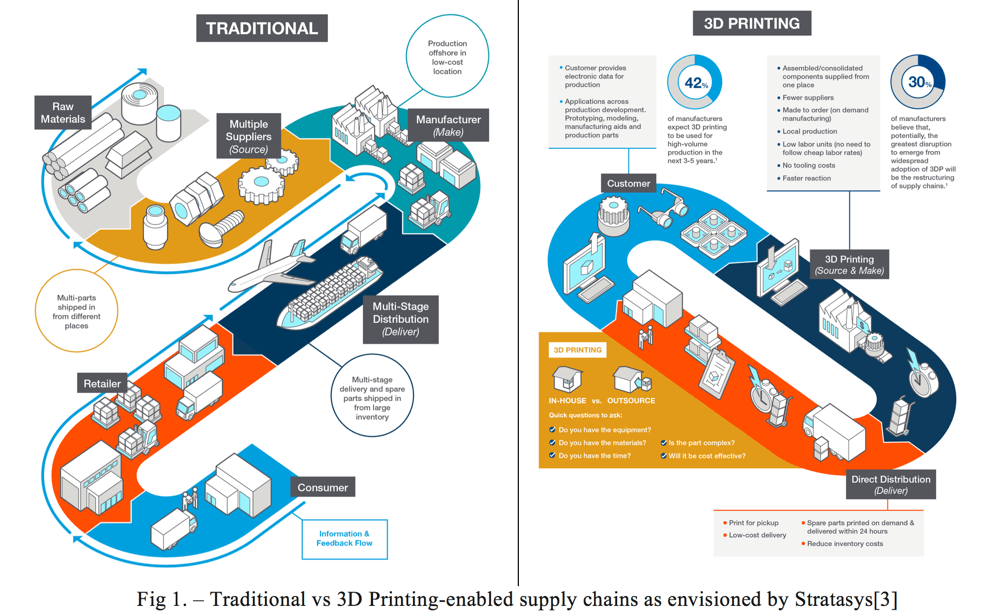

Looking ahead, the future of 3D printed clothing is filled with opportunity. While the ability to print clothing is available now, the tools and processes behind customized fit are still in their infancy. Ministry of Supply has the opportunity to pioneer the development of these tools and offer value to their customers through personalization, where traditional retailers may fall short. Beyond customization, 3D printing can push the idea of just-in-time inventories to the extreme, printing off new inventory in direct response to demand with minimal delay. 3D printing can reduce the supply chain to the delivery of raw materials, largely eliminating the need to predict consumer demand and providing significant cost savings. 3D printing has also been demonstrated to be more cost-effective at smaller quantities than mass manufacturing (fig. 2)[7]. Given the nature of the fashion industry, which employs many different colors and sizes of clothing articles, it may fall closer to cost-effectiveness via 3D printing than other industries such as household goods or electronics that utilize plastic injection molding.

Ministry of Supply is pushing clothing design and retail to the cutting edge of the future, but trailblazing doesn’t come without hiccups. Developing the tools to tailor custom fit may be more capital intensive and challenging than anticipated, and there are still concerns about the cost-effectiveness of 3D printing, which hasn’t proven to be particularly cost-savings in most retail manufacturing settings. Furthermore, the company may face challenges regarding returns if their products are custom-produced. Perhaps there are other industries from which Ministry of Supply can take lessons? Here’s hoping they figure it out so we can all find perfect fits! (799)

References

[1] Schiffer, Jessica. “Ministry of Supply Is Betting Big on the Power of 3D Printing.” Digiday, Digiday, 23 May 2017, digiday.com/events/glossy/ministry-supply-betting-big-power-3d-printing/.

[2] Takada, Kazunori, and Emi Urabe. “These Hi-Tech Knitting Machines Will Soon Be Making Car Parts.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 1 Oct. 2017, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-01/heir-to-1-9-billion-knitting-empire-is-taking-it-into-car-parts.

[3] “3D Printing Impact on the Supply Chain | Infographic | Stratasys Direct.” Stratasys Direct Manufacturing, www.stratasysdirect.com/resources/3d-printing-supply-chain-infographic/.

[4] Koslow, Tyler. “UPDATE: Just3DPrint Loses Defamation Lawsuit Against 3DR Holdings.” All3DP, 18 Aug. 2017, all3dp.com/just-3d-print-ebay-controversy-reignites-with-lawsuits-accusations/.

[5] “3D Printing and the Future of Supply Chains.” DHL, DHL Trend Research, Nov. 2016, www.dhl.com/content/dam/downloads/g0/about_us/logistics_insights/dhl_trendreport_3dprinting.pdf.

[6] Halzack, Sarah. “This Machine Can Knit a Custom Blazer in 90 Minutes – and May Herald a Clothing Revolution.” Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles Times, 29 May 2017, beta.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-custom-clothing-20170529-story.html.

[7] Bhasin, Varun, and Muhammad Raheel Bodla. “Impact of 3D Printing on Global Supply Chains by 2020.” MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, MIT, June 2014, ctl.mit.edu/sites/ctl.mit.edu/files/library/public/2014ExecSummary-BhasinBodla.pdf.

This technology seems to have a lot of potential in solving for the speed problem in the fashion industry, which would help reduce inventory cost, reduce the need to mark down inventory, and should in theory translate to cost savings. However, given where the cost of this technology is now, I think its application is quite limited to a specific price range. At a cheaper price range (for example, where fast fashion companies like Zara and H&M operate), if you want to break even on the investment into the machine alone in one year, assuming 12 hours of machine utilization per day, the machine cost per clothing piece will be around $18. This is before any raw materials or electricity cost. Given that a piece of clothing at Zara or H&M sells for $20-40 on average, the company will likely make no margins or even loss using this technology at its current cost structure. At the high end price of the spectrum, I think customers would expect hand-made clothing pieces as opposed to ones made by a 3D printer, so the cost would make sense and potentially offer very healthy margin to the company, but it requires a lot of customer education to change their expectation. I’m very interested to see how fast the cost of this technology will decline over time and at which point it will become prevalent among lower-end fashion companies.

While your article emphasizes the overall benefit to the supplier of the product by reducing the supply chain, the consumer side would not be necessarily better off with a 3D printed product. Why? Well, first of all, the set up time for each printing session may last in the order of several minutes, if not hours. In a world where people expect products and services to be provided “on demand” 3D printing offers sacrifice choice over ubiquity.

Also, the retailer utility of 3D printed products has been hotly debated in the past few months. While printing your own t-shirt, for example, may have a “cool” factor as a consumer, the overall cost per unit increases dramatically for the retailer. This happens because you cut away part of the economies of scale that benefit the producer of textiles and clothing, and you instead shift costs downstream in the form of expensive equipment ($160k), trained staff, retail space, and sourced materials. I agree that some retailers may be able to invest in these technologies, but I think that true adoption would be slow at the smaller retailer space because the current sourcing alternative is much cheaper and easier to use.

Thank you for the well written article. I agree that the prospect of 3D printed clothing is very interesting and potentially disruptive if it can reach scale and popularity. Thinking about how this type of technology might grow: if this becomes more popular, will the decentralized and less capital-intensive nature of this technology result in an emergence of individuals or smaller organizations who can specialize in creating unique designs? And will customers, in general, be willing to pay a premium for these distinct fashions? Another potential issue I saw involved the designs themselves. With traditional clothing manufacturing there are checks in-place to ensure that a company’s products meet a certain threshold of quality and customer satisfaction. If customers have a large degree of flexibility in creating these designs, how can Ministry of Supply ensure that the product does not suffer from quality issues and potentially result in negative implications for their brand?

I am very in favor of 3D printed clothing, but perhaps on a more subtle scale. I don’t think the average consumer has enough artistic vision or creativity to design their own clothing, so I’m imagining a world where brands and designers design clothing “templates” that can be tweaked by the consumer. Consumers will be able to choose the item’s color, material, length, loose / tight fit, button / zipper designs, etc. This concept of “tweaking” professional designs has already been rolled out by several major brands. Coach has launched “Coach Create” where customers can control the color and appliques of their purses (not their shape or design), while Fame & Partners sells dresses that have color, length of sleeve, and skirt shapes chosen by the customer. 3D printing will allow these brands to customize even further, while still maintaining control of what exactly consumers can tweak. In this manner, consumers will still be confident that they will have a stylish, well-designed item of clothing but also the satisfaction of having a one-of-a-kind item.

Coach: http://www.coach.com/shop/create-customize-make-your-bag?spu=0&gclid=Cj0KCQiAmITRBRCSARIsAEOZmr4xPmjtPzZ5KF7dWBD8z8P9yCkFIoh6qzPN01ixMzo-VbAqzih7xqAaAsGeEALw_wcB

Fame & Partners: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/fame-and-partners-launches-custom-evening-wear-collection-300428637.html