Knewton: Can the Education Industry Teach Itself a New Trick?

This post explores how Knewton, a digital education company, is using adaptive learning software to disrupt an antiquated schooling system.

Sparked by the industrial revolution, improvements in technology have driven dramatic increases in global per capita wealth. [1] The beneficiaries of across-the-board step changes in the quality of housing, healthcare, entertainment, communication, transportation, etc., today’s middle-class-citizens arguably live better than the royalty of the Middle Ages.

However, as economist Thomas Piketty argues in his book Capital in the Twenty First Century, the accelerating pace of technological innovation may have a pernicious, unintended consequence: growth in income inequality as workers are replaced with high return-on-investment machines. [2] Viewed pessimistically, technology could inadvertently lead to the permanent stratification of society into the socioeconomic elite that inherit vast wealth and workers that lack the capital and knowledge to catch-up.

Amidst these concerns, Knewton, a digital education company founded in 2008, is attempting to revolutionize one of society’s great democratizing forces—broad access to a high-quality education.

Today’s Antiquated and Expensive Education System

The market opportunity for Knewton arises from not only advancements in digital technology but also the stagnation of the education system over the past century. While the operating models utilized in most industries today bear limited resemblance to those of their 19th century predecessors, the education system in the United State remains virtually unchanged since Horace Mann, inspired by an 1843 visit to Prussia, institutionalized the factory-model classroom. Interestingly, Mann designed this large-group learning model based on a desire to ease the religious tensions between Protestants and Catholics and create a more tolerant society—not because of the educational efficacy of the system itself. [3] Mann’s blueprint places children into an impersonal, age-based and inflexible learning environment that advances students almost solely on the basis of amount of time spent in the system. [4] While this structured environment works for some, it is a self-esteem-crushing disaster for others. 32 million adults in the United States are illiterate, and 21% of all adults read below a 5th-grade level. [5]

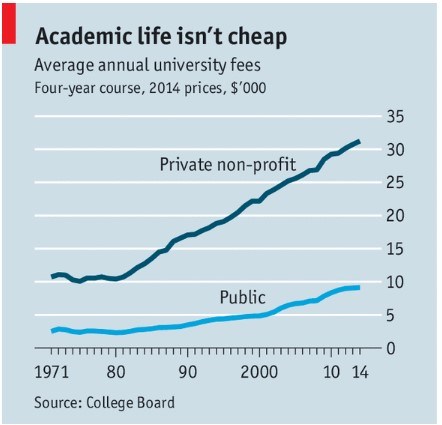

In higher education, colleges and universities struggle to contain increasing tuitions as budgets balloon to support administrative personal and professors. Average annual fees at private universities grew to $31,000 in 2014, a rise of approximately 200% since the 1970s (see chart below). Student have struggled to keep up with the mounting bills and increasingly rely on loans. The average college student now graduates with $40,000 in debt, and student debt in the United States totals $1.2 trillion (a 3x increase over the past decade). [6][7]

In this context, a tremendous market need exists for scalable innovations in education that will drive better outcomes at lower costs.

The End of the #2 Pencil?

HBS graduate and CEO of Knewton Jose Ferreria believes his company has harnessed emerging digital technologies to develop a solution. A 1984 study by psychologist Benjamin Bloom found that students given personalized lessons performed two standard deviations better than peers in a control group. [8] Leveraging this research and work in the fields of adaptive tutoring systems, psychometrics and cognitive learning theory, Knewton developed software that integrates existing educational content into an individualized, digital adaptive learning experience for students. Developed over seven years at a cost of $100 million, the software provides users a meaningfully improved experience at a low marginal cost with benefits including: [9] [10]

- Personalized pacing, content, exercises and recommendations for students

- Detailed performance analytics for teachers and students

- Content insights for application and content creators

More than 10 million students have already used Knewton’s products. [11] The company’s go-to-market strategy involves licensing its technology to established education publishing players like Pearson, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and Cambridge University Press. The software’s open architecture allows publishers to overlay existing educational content and create unique products which are then marketed to universities and the K-12 market. [12]

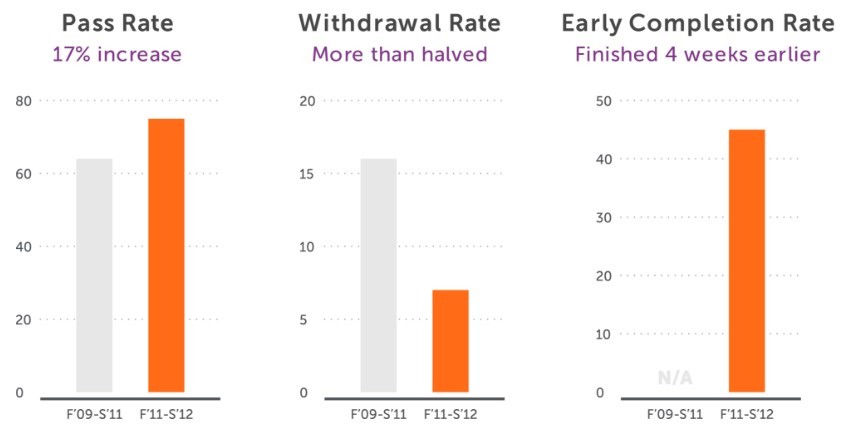

Knewton is compiling compelling data on its efficacy versus traditional teaching methods. The company recently partnered with Arizona State University to create a Knewton-powered mathematics course. The impact was impressive: passing grades increased 17%, withdrawals fell by approximately 50% and 45% of students finished 12 weeks early. [13]

Moving forward, Knewton will have to grapple with student-privacy issues and a lack of control over the quality of the 3rd-party educational content integrated into its product. On the other hand, it has a tremendous opportunity to take advantage of the power of machine learning as it leverages a growing amount of data to generate the optimal student learning experience and further drive a performance wedge between adaptive and traditional teaching methods.

As a final thought, I’d hope to see the application of this technology extended to adult education. The accelerating rate of technological change will only lead to further dislocations in the labor markets. Affordable and effective adult learning programs are desperately needed to retrain displaced workers and help ensure society doesn’t devolve into the bleak “haves and have nots” future envisioned by Pikkety.

[Word Count: 800]

References:

[1] Derek Thompson, “The Economic History of the Last 2000 Years: Part II,” The Atlantic, http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/06/the-economic-history-of-the-last-2000-years-part-ii/258762/, accessed November 2016.

[2] Paul Krugman, “Why We’re in the New Gilded Age,” The New York Review of Books, http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2014/05/08/thomas-piketty-new-gilded-age/, accessed November 2016.

[3] Joel Rose, “How to Break Free of Our 19th-Century Factory-Model Education System,” The Atlantic, http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2012/05/how-to-break-free-of-our-19th-century-factory-model-education-system/256881/, accessed November 2016.

[4] Jose Ferreira, “Personalizing The Factory,” TechCrunch, https://techcrunch.com/2015/06/17/personalizing-the-factory/, accessed November 2016.

[5] The Huffington Post, “The U.S. Illiteracy Rate Hasn’t Changed In 10 Years,” http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/06/illiteracy-rate_n_3880355.html, accessed November 2016.

[6] The Economist, “The log-on degree,” http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21646219-college-america-ruinously-expensive-some-digital-cures-are-emerging-log, accessed November 2016.

[7] The Economist, “More is less,” http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21661008-more-less, accessed November 2016.

[8] Michael Moe, “Classrooms of the Future,” OZY, http://www.ozy.com/pov/classrooms-of-the-future/66311, accessed November 2016.

[9] Kevin Wilson, Zack Nichols, “The Knewton Platform,” https://www.knewton.com/wp-content/uploads/knewton-technical-white-paper-201501.pdf, accessed November 2016.

[10] Lyndsey Layton, “A personal tutor available at the click of a mouse,” The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/a-personal-tutor-available-at-the-click-of-a-mouse/2015/08/26/ed05ac70-4aa0-11e5-8e7d-9c033e6745d8_story.html#comments, accessed November 2016.

[11] Knewton, “About,” https://www.knewton.com/about/, accessed November 2016.

[12] IBID

[13] Knewton, “Results,” https://www.knewton.com/approach/results/, accessed November 2016.

MicMacMan, I found this post to be incredibly insightful, particularly after today’s class on IBM Watson. As machine learning and artificial intelligence can guide a physician to correctly diagnose and provide treatment to a patient, its clear to me that these impacts can occur in the classroom as well, as AI software can guide students through materials at their individual pace and assess their performance objectively. As teachers begin to integrate this technology into the classroom, however, I’d be worried about a few things. First, AI technology is expensive, and only the most well-funded school districts and private schools will likely be able to afford this technology, creating an even greater disparity between the “haves and have nots.” If the technology is sold to state governments who can distribute it in an equitable way across its public school systems, this may be one way to ensure that every child is able to access personalized learning through Knewton’s technology. Second, as students go through school, they learn a lot more than simply classroom subjects – through being in a classroom and interacting with peers, students learn how to treat others, how to converse, how to make decisions, how to influence and persuade, and who they would like to be in a school-based society. I would want to be careful that these softer elements of learning remain in place, even if computers are replacing the actual teaching of subject materials.

Thanks for the post. Knewton seems like they’re onto a really great thing here and I firmly beleive that the educational system and accreditation in the United States and globally – likely led outside of the U.S. – will look very different in 30 years as a result of initiatives like this one. Have they (or you) thought about how they would implement such a system in the Unites States’ current educational ecosystem? Until an education firm or movement can effectively address the politics of education, little will change. I struggle with how this can be achieved, and maybe it is inevitable once alternative options such as Knewton become so compelling that the student and parent demand flock away from the existing institutional system and toward the newer, more effective methods of education. I hope this happens sooner rather than later or the U.S. is especially in for a rude awakening.

I really enjoyed reading this post which gave lots of clear context for thinking about how education has and hasn’t changed over time compared to other parts of the economy.

Knewton’s progress is very impressive. I echo though some of PThati’s concerns about the varied roles that schools and classroom environments provide, not all of which are captured in academic testing. I’d imagine that even if personalized learning helps in one course at the margin, that its effects scaled up across a school environment may be more underwhelming because of the very different social and group experience schools provide.

I wonder if Knewton has thought about which kinds of subjects are better or worse suited for personalized learning – math seems ideal to me – as well as how different kinds of learning styles may work better or worse with its technology. Perhaps part of the future of personalized learning is learning about the kinds of people who learn best in groups too and helping them too.

MicMac,

It’s hard not to get excited about the prospect of harnessing technology to provide high-quality, low-cost education to children and adults alike. Even if there are some concerns (like privacy), companies/sites like Knewton, Khan Academy, and Wikipedia really do seem to represent the best of the Internet age.

But while education has indeed been “one of society’s great democratizing forces” for the past several centuries, I can’t help but wonder if this will continue to be true in the future. As technological change renders more and more jobs obsolete, I worry that there may simply not be enough jobs to keep our global labor force gainfully employed. This idea has gotten a lot of attention in the past few years and was the subject of an Atlantic cover story last summer.[1] While it sounds like science fiction (and may indeed prove to be), I think the post-work world is worth taking seriously if for no other reason than because doing so forces us to reexamine our assumptions about education. Do we educate young people in order to prepare them for the work force…or for life in general? Is there a difference between the two? Should there be? What if work no longer serves as society’s primary organizing force? What if robotics render Toyota factory jobs obsolete, and Watson’s successors put MBAs, JDs, and MDs out of work?

I’ve got no answers…just a bunch of obnoxious questions. But I love that you connected Knewton to bigger issues like capital and social order because it forced me to think–if only for a moment–about those big, obnoxious, impossible-to-answer questions.

[1] http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/07/world-without-work/395294/

Great post, thanks! I agree that it’s hard not to get excited about the potential developments machine-learning and digital technology could bring to the field of education. It feels like we are moving more and more towards customizing everything, but we have yet to really figure this out with education. Last year, I learned about a similar organization, called Teach to One, which was originally started in New York City. Teach to One developed a math curriculum, using machine learning to completely personalize the teaching plan for each student, and also had huge success. What I found interesting about Teach to One, is that they also used the technology to determine what teaching styles worked best for each student, and would tailor the daily teaching plan based on this information. While Knewton sounds more flexible since it allows schools and publishers to use their own content and integrate the tool into their existing teaching system, I also like the idea of redeveloping curriculums to take better advantage of machine learning. There are definite trade-offs to both, particularly when considering less quantitative subject areas, but I definitely agree that this has huge potential either way.

Technology has the potential to reinvent the way we teach and the way we learn. I see funding, especially in cash-strapped public school systems being the reason connected classrooms are slow to be adopted. While this technology has proven results and a direct impact on grades, I foresee school being resistant to adopting an expense investment in bringing this tech into every classroom. Administrators will be faced with tough trade-offs when looking at the potential benefits of connected and adaptive classrooms while they look at cutting extra-curriculars to offset rising costs. What changes could be made to this model to encourage wide spread adoption, especially in poorer school districts that struggle with grades and graduation rates?