Isolationist Trade Policy Drives General Motors to Narrow its Scope

Protectionist trade policy drives General Motors, one of the world's largest automakers, to localize its global supply chain.

“Localization is another important tenet of our value chain. Localization lowers risks by increasing the flexibility of our supply chain to respond to disruptions caused by natural, political or other causes…”

– General Motors 2016 Sustainability Report[1]

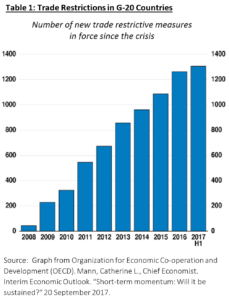

During President Trump’s Asia tour last week, eleven countries announced a preliminary renegotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. While the US was the leading architect of the original deal, President Trump concluded that the US would not be party to the renegotiated contract. The US is not alone in its isolationist policy choices. Protectionist politics across the globe have resulted in a sustained backlash against free trade. As shown in Table 1, global trade restrictions have been mounting for the past decade. The impact on trade volume has been staggering: 2011 was the last year in a consecutive, 30-year trend of trade growing at twice the rate of global GDP.[2]

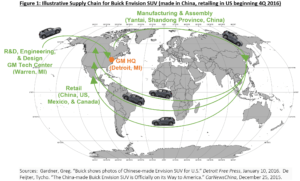

General Motors (GM), has every reason to be concerned. GM’s multi-national supply chain encompasses manufacturing, distribution, and warehousing operations in 61 countries, with major assembly hubs spattered across 17 countries and six continents (see supply chain for GM’s Buick Envision SUV in Figure 1).[3] However, escalating isolationist trade policies threaten to make GM’s multi-national strategy untenable through costly import tariffs that would obstruct GM’s global flow of goods.[4] To manage this risk, GM is winding down its operations in less profitable geographies in the near-term, and deploying the additional resources that it derives from each exit into localized supply chains that depend less on the multi-national movement of goods over the long-term. In 2015, GM ended manufacturing in Australia and exited Russia. This year, GM sold off its European[5] and South African operations.[6]

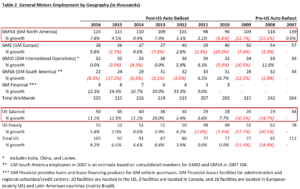

GM has since announced plans to open a 1.2 million square-foot supplier park near its manufacturing facility in Texas in 2018. The park will relocate 600 jobs previously performed outside the US, and employ an additional 650 people.[7] Notably, Table 2 reveals that GM has been expanding in the US over the past seven years, likely in response to trade pressures given that the company’s US sales comprise only 30% of its total sales volume, with the vast majority of sales occurring outside of the US.[8]

GM has since announced plans to open a 1.2 million square-foot supplier park near its manufacturing facility in Texas in 2018. The park will relocate 600 jobs previously performed outside the US, and employ an additional 650 people.[7] Notably, Table 2 reveals that GM has been expanding in the US over the past seven years, likely in response to trade pressures given that the company’s US sales comprise only 30% of its total sales volume, with the vast majority of sales occurring outside of the US.[8]

Last month, GM purchased Strobe, a California-based company that develops laser-imaging technology for driverless cars.[9] This acquisition complements GM’s purchase of California startup Cruise Automation, a driverless car developer. GM has been able to integrate autonomous features into its Chevrolet Bolt electric sedan, which is manufactured in Michigan.[10] A vertically integrated, localized supply chain for a product like this reduces the risk of import tariffs and allows GM to increase its speed of execution and delivery to market, albeit at an increased cost of production.

As GM works to ensure that its operations in any given country are independent of the company’s operations elsewhere around the globe, GM should manage several key risks. In a world where GM’s operations are geographically constrained, it becomes increasingly vulnerable to supplier risk. GM should therefore diversify its supplier base in each country. In addition, GM should invest in talent. Skilled labor will be critical to GM as it expands its US workforce. The US shed millions of manufacturing jobs over the last half-century, and with them workers who could have been uptrained to operate equipment that has become more automated and reliant on new technologies.

As we watch GM grapple with these changes, the impact of trade restrictions on labor, the most basic component of a supply chain, begs for deeper consideration. The advantage of manufacturing internationally is starting to disappear even without the added cost of tariffs. In 2004, manufacturing in China was 15 percent cheaper than the US. In 2016, this disparity shrunk to one percent.[11] Does this suggest that we might not need isolationist policy to “re-shore” labor in the first place? Moreover, will re-shored supply chains be as good for jobs as isolationist regimes envision? CY TOP, an Asian company that produces stainless steel trashcans began developing plants in the US two years ago; however, the opportunity to reinvent its production process prompted the company to reduce its labor content by 88% through automation.[12] If the goal of isolationist trade policy is to spur job growth, then do we risk losing more than we gain? Are there other impacts on labor that multi-national companies need to mitigate if trade restrictions continue to mount?

***

[1] General Motors, “2016 Sustainability Report: Supply Chain, Collaborating to Improve Mutual Performance.” http://www.gmsustainability.com/manage/supply.html

[2] Donnan, Shawn, “Trade: Into uncharted waters.” Financial Times, October 24, 2013.

[3] General Motors, December 31, 2016 Form 10-K.

[4] Historically, costly US tariffs have resulted in retaliatory tariffs imposed on the US by other countries. This has almost always hurt US industries, companies, and jobs. By way of example, when the US failed to comply with a NAFTA provision that permitted Mexican truckers on US roads in 2009, Mexico responded with duties of up to 25% on farm goods, resulting in $984 million of lost revenue for US farmers exporting to Mexico. Dollar figure captures lost revenue among US farmers while duties imposed by Mexico were in place from March 2009 through October 2011. Source: Zahniser, Steven, Tom Hertz and Monica Argoti, “Quantifying the Effects of Mexico’s Retaliatory Tariffs on Select US Agricultural Exports,” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, Volume 38, Issue 1 (2015): 103.

Similarly, when the US imposed antidumping duties on Chinese solar panels in 2012, China responded with duties against US silicon, which prompted Hemlock Semiconductor to abandon its planned construction of a $1.5 billion silicon plant in the US. Source: Reuters, “Here’s How Donald Trump’s Trade Policy Could Backfire,” March 24, 2016.

[5] Snavely, Brent, “General Motors Completes Sale of Long-Languishing European Division,” Detroit Free Press, August 10, 2017.

[6] “General Motors Restructures International Markets to Strengthen Global Business Performance,” General Motors press release (Singapore, May 18, 2017).

[7] “GM Brings Parts of Supply Chain Back to US,” MH&L press release (Texas, USA, June 20, 2017).

[8] In 2016, GM’s China sales accounted for 39% of its total worldwide sales, and its US sales accounted for 30% of total sales. General Motors, December 31, 2016 Form 10-K.

[9] Bhuiyan, Johana, “Why GM is vertically integrating as it moved deeper into making self-driving cars,” Recode.Net, October 9, 2017. https://www.recode.net/2017/10/9/16446768/general-motors-acquisition-lidar-sensor-startup-strobe-self-driving

[10] Vlasic, Bill, “GM Acquires Strobe, Start-Up Focused on Driverless Technology,” New York Times, October 9, 2017.

[11] Rose, Justin and Martin Reeves, “Rethinking Your Supply Chain in an Era of Protectionism,” Harvard Business Review, March 22, 2017.

[12] Rose, Justin and Martin Reeves, “Rethinking Your Supply Chain in an Era of Protectionism,” Harvard Business Review, March 22, 2017.

On a broad level, I think the impact of isolation movements on large companies like GM is enormously significant, even if the company has seemingly positioned itself to produce more vertically inside one country. This effect is due to GM’s tremendous dependence on suppliers; its supply base, the location of that supply base, and the corresponding impact to the supply chain are crucial elements to GM’s success. GM requires tens of thousands of diverse manufactured parts, raw materials, and suppliers to produce a single vehicle. Despite GM’s immense purchasing power and resources, it’s challenging to develop high quality, high performing, competitively priced suppliers. It may be impossible to optimize location, capability, and price. For example, GM may only have a few suppliers globally capable to produce a highly technical electric component required in millions of vehicles each year, all of which may be located in China.

Although GM has closed several of its international production facilities, its manufacturing locations in the US depend heavily on a very diverse and geographically spread-out supply chain. GM has even pushed many US-based suppliers to operate in Mexico to minimize the cost impact to the product supply chain. Could those very product chains now be in jeopardy, as trade tensions rise between the US and Mexico? US trade policies may be trending towards manufacturing isolationism, but I’m very doubtful that the complex automotive supply chain can be localized in a cost-effective way. If this trend continues however, how could GM remain both profitable and competitive?

As you mention, the biggest risk to current domestic jobs is the threat of automation. Growing isolationist trade policies, further spurred by President Trump, may be successful in bringing back some domestic jobs like those in GM’s Texas manufacturing facility. Yet are these the right jobs to bring back? If automation continues and these jobs are replaced, the US may be at a disadvantage without an international footprint in such industries. Perhaps these jobs would have been lost overseas, with new ones emerging domestically given the improvements in automation. Overall, it seems like a short-term solution that might cost GM significant competitive advantage in the future.

I agree that it is critical for GM to invest in talent to ensure a continuous supply of skilled laborers. But what are some of the ways in which GM can effectively do that? Moreover, can GM invest in generating domestic talent (versus outsourced talent)? To Chris’ point, above, isolationist trade policies may only bring low-skilled jobs back to the US in the short-term. Then, those jobs will be eliminated by developments in automation. I have often heard that many companies, like GM, are desperately trying to fill highly-skilled positions. Yet, these positions simply remain empty since the talent pool is so limited. How can GM work to increase the supply to these talent pools?

Eleonora, this was a great read. First of all, I was shocked at the statistic that manufacturing in China was now only one percent cheaper than the US – I definitely thought that the delta was a lot larger. At a high level, I believe that isolationism in this globalized era may not be the best solution for GM. Below are a few reasons that you did not get the chance to touch on in your post.

(1) Oxford Economics released data that showed labor costs adjusted for productivity in China are only 4 percent cheaper than in the U.S. today [1]. CNN further explained that this small gap is due to wages in China rising much faster than increases in productivity [2]. CNN then states that “productivity has doubled in India and China, but the U.S. remains as much as 90% more productive than the two developing countries.” One could posit that productivity in China doubles again, and this will significantly close the gap with U.S. productivity. If wages in China doesn’t increase commensurately, then labor cost adjusted for productivity in China will again be significantly cheaper than the U.S. In a world like this, it would again be very economical to locate GM’s manufacturing in China.

(2) The USD/CNY exchange rate will meaningfully impact the costs of locating manufacturing in China. The Dollar has strengthened meaningfully against the Yuan since 5 years ago, but more recently, has exhibited a weakening trend [3] due to policy moves and intervention by authorities. Despite this recent phenomenon, analysts are still expecting the Dollar to continue strengthening against the Yuan in the coming years. If this turns out to be true, then wages in China will also get cheaper relative to the U.S.

Both of these examples show how isolationism might hurt GM, at least on the labor cost aspect.

Footnotes:

[1] http://www.oxfordeconomics.com/about-us/oxford-economics-in-the-media/press-coverage/made-in-china-not-as-cheap-as-you-think

[2] http://money.cnn.com/2016/03/17/news/economy/china-cheap-labor-productivity/index.html

[3] http://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=USD&to=CNY&view=5Y

In general, isolationist policies impede firms from operating at the lowest cost around the globe. For GM, trade restrictions may mean more “onshoring’ but as you rightly mentioned with increasing labor (and likely material) costs, which then get passed to the consumer. Even with greater investment in the US by GM, the increased jobs will not make a material difference in employment given the ~130 million person workforce. I believe more will be lost than gained through these policies and these restrictions will serve to make GM less competitive domestically and globally.

One way firms like GM can insulate themselves from higher labor costs is to keep investing in automation. This tactic, however, detracts from the goal of US policy to create more jobs.

Super interesting article! Thank you! When you read in the news about Trump’s announcements you don’t really think about all the details. You did a great job with this example.

I feel that politicians have huge influence on the business world. The fact that every several years a new leader is elected causes instability. I think that having a policy is good, but not enough – you need to have a long lasting policy.

A bigger question that should be asked is whether it’s good to focus only on your own country’s benefit or should every country, and particularly the big western ones, should think about what’s good the entire world’s population.

If these countries don’t do it, who will?

Great read, Eleonora! I agree with Danny; while it may seem that refocusing operations in the U.S. is approximately net-neutral for GM, the likely increase in material costs alone, may yield to increased costs for GM and therefore increased prices for consumers. Additionally, isolationists policies are a headache for companies like GM. As you pointed out, GM only generates 30% of its sales from the U.S. Yet, it is still considered to be an “American” company due to its roots. Shouldn’t the company’s manufacturing footprint reflect its global sales to optimize supply chain efficiency? How can the U.S. coerce companies to be more “American” when they have in fact become “global”? I believe companies like GM should think more carefully about all of their stakeholders (incl. shareholders and customers) when reacting to isolationist trade policies.

Great article! It is really interesting to see how a company that has spent many years diversifying their supply chain and building out their operations in many different regions is working on unwinding that due to protectionist policies.

One of the things that struck me most about this article was the question about whether or not we need isiolationist policies in the first place given that the cost benefit to manufacturing in China has reduced to almost zero. While this may be true about China, I I wonder though if this stat doesn’t account for the fact that there are other regions that are now much cheaper than China for manufacturing. As discussed in class, it is becoming cheaper to produce in places like Africa and in the absence of isiolationist policies, GM may benefit from manufacturing in countries that are now cheaper than China.

Given that policies will continue to change and the costs of manufacturing in different markets will change as well, GM will need to remain nimble and flexible so that they can continually adjust their supply chain to meet the needs of their customers.

This is super interesting, Eleonora! Like several other commentators above, I am intrigued by your question regarding the necessity of isolationist policies to bring jobs back to America. With cheaper energy costs unleashed by the shale gas revolution in this country and rising labor costs in Asia, America is gradually closing its cost competitiveness gap with offshore production locations. One negative implication of isolationist policies you did not have a chance to raise is retaliation. In a world where American high-tech products and professional services are still much coveted in overseas markets, any unilateral action by the Trump Administration to raise trade barriers may trigger reciprocal trade restrictions on American companies doing business abroad. Given the increasing importance of China and other emerging economies as end markets for American goods, a trade war initiated by the US may well end up in a lose-lose situation. If the Chinese start to reciprocate by levying 50% tax on iPhones, Chinese buyers may switch to domestic brands like Xiaomi, causing job losses in the US tech sector. After all, trade occurs when both parties receive a benefit. Trying to artificially restrict trade takes away from the mutual benefit.

Great insight here on what is actually contrary to public perception about US labor being so expensive. You mention a recent trend that the disparity in manufacturing costs has reduced to 1%, which begs the question of whether the aggregate cost with shipping could now be higher versus manufacturing in the US. The main exception here would be markets in which GM gets a regulatory advantage for producing locally in respective markets, such as the 25% tariff China charges Tesla and companies alike for importing.

Great post Eleonora! It made me want to read more about the pros and cons of manufacturing in China vs USA. I found a great article, linked below, that covers a textile manufacturer who is actually moving his plant to the United States to actually save on costs! He mentions cheaper electricity, land (located in North Carolina), and cotton and, even though labor is roughly twice as expensive compared to China, it leads to a 25% savings per ton of textile. Other advantages he cites are that the US government is much better at leaving businesses alone compared to the Chinese government and that if Trump’s corporate tax cuts are successful the advantages will be even more pronounced.

The rising popularity of Chinese companies moving to America still only includes capital-intensive businesses as opposed to labor-intensive. For example Fuyao Glass and their Ohio plant are mentioned from our TOM case. I’m curious to see if made in China will soon be a thing of the past as domestic manufacturering makes a resurgence.

Reference: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/30/made-in-china-could-soon-be-made-in-the-us.html

I wonder what the relative importance of i) environmental events; ii) all-in production costs given the decreased wage disparity vis-a-vis China that you mention; and iii) protectionism is in GM’s calculus. Supply chains become more fragile in a world with more natural disasters, and automation in the US plus rising labor costs in China work to narrow the cost disparity as Dennis and Chris touched on.

So after accounting for those two factors, and the fact that cars have more and more embedded technology that may require closer, high-skilled supervision, how much of GM’s decision is really driven by protectionism? That is, do you think protectionism is the driving force or the icing on the cake as it relates to the industrial logic of sourcing labor in the US?

As you point out with Table 2, it is certainly notable that GM has been hiring in the US for some time (since the financial crisis) – over the same period that G-20 trade protections have been increasing. But how closely do you think that a growing quantity of trade restrictions in a general sense specifically affect automotive OEMs? Mexico is an interesting specific counter-example, where foreign auto OEMs have actually consistently increased investment in the past several years [1]. I get the sense that automotives may be a fairly stable good from the standpoint of protectionism, or even going the other way, i.e. India has and likely will continue to heavily tax imports [2], and China is actually considering relaxing foreign ownership restrictions on automotive subsidiaries [3], etc.

[1]http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/will-us-trade-policies-disrupt-mexicos-auto-sector/

[2]http://blogs.worldbank.org/psd/how-do-import-tariffs-cars-affect-competitiveness-case-india-and-pakistan

[3]https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trump-asia-china-autos/china-plans-pilot-scheme-easing-foreign-auto-firms-ownership-limits-idUSKBN1D914C

Thanks for the article Eleonora! It is surprising to see the development of protectionism in the modern world. In many instances, the decision to move in this direction is myopic in the sense that it limits itself to first-order consequences (forcing industries to produce inside the country = more jobs) when in reality the consequences of this measure are heavily dominated by combining effects – the economy will restore its balance through adjustments: local (company will change their production plans to suboptimal), regional (relative prices will accommodate inefficiencies in the supply chain) or global (currencies, inflation and interest rates will be impacted). [1]

[1] Plender, J. (2017), “Trump trade blind to global cost of protectionism”. Financial Times. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/2bee373a-e786-11e6-893c-082c54a7f539 (Accessed: 30 November 2017).

This was a great read – really like how you tied in local news with Trump’s anti-partnership with the TPP agreement to how this impacts big companies like GM. I completely agree that it’s a huge risk for GM to have less diversified supplier bases not only across countries but even within countries. And while I think it’s great that GM is opening a supplier park in the US, I also have to wonder how this will impact GM’s profitability in the long term, particularly if this trend continues – given that US labor is more expensive than most other regions. It could also work the other direction too, which brings potentially more worry – if we are not part of this partnership, other companies may move services / jobs outside of the US, and we may too be faced with more import taxes and duties.

Investing in automation is definitely a great long-term investment that will pay dividends, but in the short and medium term I think GM needs to tread carefully to make sure they maintain their competitive advantage while finding ways to diversify their supplier base.

Great read! Protectionism will certainly increase costs for the company (and thus the customer) in all geographies as GM will no longer be able to optimize its supply chain. However, I do think these costs will be mitigated by a few factors:

1) As mentioned above, increased automation has the potential to mitigate the increased labor costs of local manufacturing. While it will hurt the overall volume of jobs produced, the savings for the consumer will be realized quickly.

2) Increased adaptability in manufacturing. As manufacturing technology continues to improve, production processes will become more adaptable, reducing the cost of changing the model/type of vehicle produced at any given factory and optimizing production for the “local” market. This would allow GM to provide more value to its customers (by producing exactly what they want) and reduce distribution costs (by producing it as close as possible to the end consumer).

Eleonora, great essay which throws up many interesting points! Like many other commentators I was shocked to see that the gap between manufacturing costs in the US and China has all but disappeared. As you allude to, it has been automation and productivity improvements rather than globalization that has eroded employment in the US auto industry. Despite US auto production levels at all-time highs with 17.5 million light vehicles sold in 2016 – 40% higher than 1990[1] – employment levels remain below 1990 levels[2] as manufacturers produce nearly 1.5x the number of vehicles per worker today than they did in 1990.[3] Moreover, I worry that not only are governments merely delaying the inevitable by pursuing isolationist policies to preserve auto employment, but given that the market share of the “Big 3” of US auto (Ford, GM, Chrysler) has fallen from 90% in the 1960s to below 50% today,[4] are they effectively missing the forest for the trees by allowing half the revenues from the US auto industry to flow to international companies? Would reinvesting these profits in the US or allowing them to accrue to US shareholders be of greater economic value to the US as a whole rather than inhibiting overall economic growth by pursuing isolationist policies to save a handful of jobs?

References:

[1] https://www.statista.com/statistics/199983/us-vehicle-sales-since-1951/

[2] Bureau of Labor Statistics (https://data.bls.gov)

[3] https://ark-invest.com/research/tesla-production-efficiency

[4] http://www.epi.org/publication/the-decline-and-resurgence-of-the-u-s-auto-industry/

I think this is quite potently written. I think that the move for GM should be to protect its brand ID. Part of its customer’s promise is the American made cars. But they should capitalize on the opportunity to build on that brand credibility. Even further, they have to contend with the powerfully strong data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that proves that many jobs have in fact left the United States as a result of free trade agreements. However, in what way does dealing with these isolationist policies contort their ability to fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities to maximize shareholder value. Essentially, if they can cut costs and maximize profit potential by moving jobs to other countries, then they might be running against the precipice of a significant internal conflict.

Great article. One of the concerns I have with the responses to the more isolationist policies is the fact that more companies may focus on automating which could significantly reduce the utilization of the current labor force. Furthermore, many individuals who are out of jobs are older. In fact, 1.3 million Americans age 55 and older are looking for work but unable to find it, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (1). I believe this trend is going to create significant issues around unemployment and retraining that are going to be difficult to navigate as automation becomes more prevalent.

(1) http://thehill.com/blogs/pundits-blog/economy-budget/335896-workers-wanted-skilled-labor-shortage-hinders-business

Localization of General Motors’ supply chain may be driven by factors other than isolationism. For example, as the quality of living and labor expenses in emerging economies rise, one could expect the historical savings generated from offshoring production to dissipate. This impact is likely compounded by the labor surplus generated by automation that will drive down labor expense in the developed world as well. Thus, the benefits of localized production (such as JIT delivery) may be driving the decision to shift production rather than geopolitical dynamics.

Great paper, as you discuss and present a very relative and important topic which is broad reaching through the business and political arenas. GM is a global brand that is changing the way it operates due to nationalistic and isolationist views of many. It will be interesting to see how global sales and revenues are impacted by the stance GM is taking, and how it is re-positioning it’s supply chain management and structure in line with changes in the TPP as well as general feelings towards free trade. Additionally, I think the automation topic was initially separate and unique from the isolationist stance, but now that companies such as GM are altering their business model in line with the isolationist view – they are concurrently taking advantage of this opportunity to implement improvements to the production process via automation.

Great post! Although isolationist trade policies, such as manufacturing in the US, will help increase domestic jobs I’m not sure that this is a viable long-term solution. In the short-run, as you mentioned, it will bring jobs back into the country. However, as companies continue to aggressively invest in technology and automation, will policies such as this one put our country at a disadvantage? With the increase in globalization and technology, It seems critically important to continue having an international footprint.

Eleanora, great article – it touches on TPP and automation; I really appreciate the deep dive into the numbers as it relates to labor costs and actual jobs lost. Two areas of interest to me that weren’t mentioned are NAFTA and the attractiveness of corporate tax rate as a company considers moving its manufacturing facilities. With tax rates, GM is still benefitting from the massive losses they incurred before the bailout, so it doesn’t necessarily affect them now but I’m sure it is a down-the-road consideration. Much rests on the US tax bill on the docket. NAFTA has not only played a role vis-a-vis GM’s manufacturing in the US but also in Canada (article below references a strike in Canada as jobs were moving to Mexico).

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-18/gm-canada-strike-crimps-output-of-automaker-s-top-selling-suv

https://www.freep.com/story/money/cars/general-motors/2017/04/28/general-motors-tax-reform/101019818/

Great article! The last point about restrictions on labor is particularly interesting. In an effort to drive up US wages through immigration restrictions, we may very well drive companies out of the US. It raises an ethical question of whether sinking or stagnant wages for many is better or worse than rising wages for fewer.

The car companies have a harder public perception battle to fight. Iconic American companies take more heat if they’re seen as shipping jobs overseas. It seems to be a tough time to be a planner at GM.

Thank you Eleanora! This is a fascinating read, and it’s obvious you did a great job researching it. My opinion is that over time, isolationist policies and tariffs will not be as needed to push companies to want to manufacture here, for a number of reasons you mentioned. First and foremost, I think that as more and more tasks get automated in manufacturing processes, the cost advantage of offshoring gets less and less. Unskilled labor will not be as necessary, and highly skilled engineers, coders, etc. will be needed (many coming from U.S. universities).

As you mentioned, if the goal of protectionist policies is to create more jobs on the home front, I’m not sure this is the best strategy. These tariffs distort the free market and fly in the face of Pareto efficiency concepts. Additionally, automation will cut many more jobs than those that are being outsourced. We’ve seen many nations attempt these types of policies in the past, and I think they are more likely than ever to be value-destroying in an economy now, given how globalized trade has become.

Fascinating topic, thank you, Eleonora! I found Andrea’s comment particularly salient. Despite GM’s intentions to localize their supply chains, the localization of some components will be out of their control as they depend on specialized production in companies for whom expanding to a local market might not be a rational choice.

What will happen? One thing that is certain is that GM will try to reduce the cost of production wherever possible, and more so if imported goods are being tariffed. First, they will look to automation to reduce their cost of production. As you mentioned, there will be fewer manufacturing jobs which is one of the intentions of the policy that is driving this change. My sense is that the trend to automation is inevitable due to its cost impact and that this policy will accelerate, but not cause, it. Second, they might try to incentivize their supplier to co-locate with their manufacturing plants or they might try to manufacture more of the components themselves. It’ll be interesting to observe their next moves.

Eleonora, this is great! I found your comment regarding the impact of isolationist trade comments on job growth really insightful. On one hand, as an international living in the US, it surprises me how many large, global companies are not open to a global workforce, preferring to not deal with the administrative headache. To that end, I guess isolationist policies are doing their job. However, I think it’s likely that the makeup of the workforce evolves as GM focuses more on engineering and innovation to compete (e.g., GM unveiled its driverless Chevrolet Bolts in San Francisco less than one week ago [1]), while previously manual production processes become increasingly automated. Surely GM would be willing to source talent globally to supplement its engineering and design efforts, while it automates to reduce costs in other parts of the supply chain, therefore countering the objectives of isolationist policy?

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/29/business/gm-driverless-cars.html

This was a very well-written and insightful article!!

It is interesting to see how the trend of international supply chain retraction is affecting many industries. For its newest aircraft the 777X, The Boeing Company has invested heavily to bring manufacturing of major components back to the United States from traditionally overseas locations. This is influenced by recent trade policies, but is also accompanied by the allure of a similar supply chain, and the increasing cost of labor overseas (as you mentioned). Though Trump will likely take credit for these moves back to the United States, I think it is important to highlight the multitude of factors that have caused companies to make such shifts over the years.

Finally, to your point on isolationism and job growth, I do think that it is misinformed to believe that short term increases in jobs will be sustained. As we are already beginning to observe, automation is quickly replacing human workers in manufacturing across industries. Though jobs will increase now, over time they will decrease as more cost effective technology replaces the workforce.

Very interesting thoughts on what the true effects of isolationist policy are and if the intended impact of the policy is manifesting in reality. You do a really good job of outlining how isolationism may actually destroy more American jobs that it creates. For example, it is interesting to note that Asian manufacturers that would have just outsourced labor to the USA are now investing in technology so automation is doing the job of would-be factory workers. This kind of R&D research is most likely happening in GM as well. Large manufacturing companies like GM have been around so long because they are such adaptable organizations and hence isolationist government policy may not be the best way to influence their practices. Additionally, as U.S. policy causes costly import tariffs and affects GM’s multi-national strategy and global flow of goods, what will the response be from the countries that they are exiting. What is the conversation in the public sector about these isolationist policies and if other countries follow up with similar policies of their own? Is the private sector worried about retaliation as well? How will big companies like GM react?

Eleonora, I really liked your analysis! I’m very concerned about the lost efficiencies in the automotive supply chain due to these protectionist policies due to loss of comparative advantage. Comparative advantage is important because even if companies in one country are more efficient producers in every part of the supply chain than another country, they will more efficient to a greater degree in certain segments. [1] This means these countries have the ability to specialize in the areas where they have the most advantage and therefore lower overall supply chain costs. Global trade also creates flexibility in the supply chain by creating multiple competitors in areas that would otherwise lead to a natural national monopoly or oligopoly. Net net, I believe isolationism in this case will lead to more expensive (or lower quality) cars for American consumers due to higher supply chain costs.

[1] Hunt, Shelby D., and Donna F. Davis. 2012. “Grounding Supply Chain Management In Resource-Advantage Theory: In Defense Of A Resource-Based View Of The Firm”. Journal Of Supply Chain Management 48 (2): 14-20. doi:10.1111/j.1745-493x.2012.03266.x.

Eleanora, thanks for providing such a thorough and interesting read on GM’s recent reactions to the threats of trade isolationism. I am actually quite surprised to read that GM is proactively implementing such significant changes as a result of the potential threat of trade isolationism. Ultimately, I believe that maintaining a strong international footprint will be quite important as innovations such as 3D printing have the ability to completely change the way goods are manufactured. While we may still be a 10 years away from this, 3D printing would essentially render tariffs obsolete as the only item that would be required to cross a border is the digital design of a product. In such a scenario, maintaining an international presence would be quite beneficial to GM, as these plants could be equipped with 3D printers and products would not have to be shipped between countries. Just additional food for thought.

Although isolationism is re-shoring jobs back to the US as of now, I wonder if this will reduce the global competitiveness of GM in long term. As you rightly pointed out, automation might reduce the dependence of costly labor but it goes against the fundamental premise of why trade policies were put in place in the first place. Also, drastic measures such as these would expose companies such as GM to inefficiencies in short-term as it might take years to set up new localized supply chains, hire and train workforces, raise fresh capital and develop new automation technologies, leaving more globalized competitors with the opportunity to create better synergies and rapidly gain market share. Another aspect to think about is social and political tensions arising out of localization of trade. Free flowing trade has been a crucial factor in global cooperation. With every country following the path of isolationism, are we trading off a global optimum for a local optimum?

A very interesting question! If trade restriction policies intend to move more jobs back on-shore, especially when at higher costs, will companies be forced to invest in technology that improves the efficiency of operations and potentially puts human jobs at risk? I recently attended a discussion at Harvard Kennedy School focused on how the transition to more artificial intelligence would impact jobs. According to the survey below [1], “Advances in technology may displace certain types of work, but historically have been a net creator of jobs.” If job creation is actually going to occur outside of the manufacturing companies themselves, and for example, create jobs for technology companies where perhaps trade restrictions are not as stringent, should government be concerned with additional policies that require manufacturers to source technology supply from within the US?

[1] Smith, Aaron, and Janna Anderson. “AI, Robotics, and the Future of Jobs.” Pew Research Center 6 (2014).