Invisalign – When IP Isn’t Enough

Invisalign created an incredibly disruptive technology, but their IP wasn’t enough to make this startup a success.

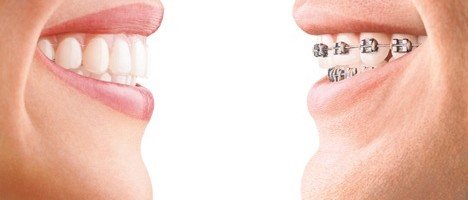

Invisalign was started by two MBA candidates at Stanford in 1999 with the premise that for some dental patients, retainers can shift your teeth just as good as traditional braces. For decades orthodontists had been realigning teeth with the large brackets cemented to a patients teeth and connected together with a metal wire. Invisalign introduced a completely different method of giving patients clear retainers every two weeks that were slightly different to slowly shift their teeth into position. The idea was enormously disruptive to the dental industry as invisalign’s sales have now reached $761M in the $6.4B orthodontic market for braces. [1] & [1.5]

Business Model:

Their business model hinges on the value proposition they provide to patients and orthodontists. Patients are willing to pay nearly double for invisalign product because of the aesthetic appeal of a clear retainer vs. the metal mouth look that accompanies traditional braces. For the orthodontists, invisalign offeres soft savings by reducing the labor time from 9-12 hours per treatment to 2-3 in turn allowing the orthodontist to increase their capacity and generate more revenues. [2]

Challenges:

However, the dental industry is not one open to drastic change. Given the disruptive nature of the technology, many orthodontists were resist to trying it and even questioned its efficacy. Additionally, the process of designing and manufacturing each individualized product was extremely intense and costly. Developing an effective operating model that could make this technology economically viable and win over orthodontists was crucial to their success.

Design Process

Invisalign focused on giving the orthodontist control over the treatment process. The orthodontist would do a 3D scan of the patient’s teeth, and send it electronically to Invisalign’s modeling facility where experts would digitally transform it into a customized simulation showing tooth movements in two week increments. Since each orthodontist prescribed unique treatments, invisalign gave the orthodontist the ability to submit feedback for revising the model, before actual production.

The intense nature of 3D modeling software made labor costs extremely high. However, all the work was done electronically enabling Invisalign to outsource this to any part of the world. The founder was originally from Pakistan, and thus successfully established a facility to handle this portion of the process there. This gave them greater control over costs.

Manufacturing:

Each retainer produced needed to be custom. Traditional manufacturing is incredible cheap for producing standard units, but when products vary on a per unit basis, the expense becomes enormous. To avoid this manufacturing pitfall, Invisalign employed emerging 3D printing technology. By partnering with 3D systems, the premier innovator in 3D printing, invisalign was able to drastically reduce their manufacturing costs. [3] In fact, by 2012 “17.2 million Invisalign braces were made. Each one of them was manufactured in a 3D printing, 24/7, lights out manufacturing facility.” [4] Furthermore, they established their production facility in Juarez, Mexico giving them a geographic advantage, a more business friendly regulatory environment, and greater control over costs.

Sales:

Despite Invisalign’s disruptive technology, strategic partnerships, and superior processes, the overwhelming challenge to overcome was convincing orthodontists to actually use the product. In the early days they made a significant marketing push for brand awareness and by the end of 2001 75% of orthodontists were trained on the company’s system. [2] However, sales weren’t growing fast enough. Rather than trying to convince traditional orthodontists, they decided to focus their sales force attention on getting current orthodontist to prescribe the invisalign product more. They developed different tiers for orthodontists based on their use of the product and then set incentives such that sales reps would devote more time to those orthodontists. A sales rep’s commission was tied to the the number of cases started. They designed their call centers and websites to directly route interested customers to orthodontists using high volumes of the Invisalign product. [2]

Conclusion:

Invisalign had a disruptive technology, but would not have been able to execute their business model without a well designed operating model. Their partnerships abroad, employment of outside 3D printing expertise, incorporation of the orthodontist’s feedback into their workflow, and alignment of incentives for their sales force with the overall strategy gave them the foundation on which to build one of the most successful startups in the dental space.

[1] Google Finance ALGN – https://www.google.com/finance?q=NASDAQ%3AALGN&fstype=ii&ei=-MJZVuDFCNezmAHYoZ8Q

[1.5] IBISWorld Industry Report OD6039 – Orthodontists in the US

[2] Kellogg School of Management – Invisalign: Orthodontics Unwired

[3] 3D Systems – http://www.toptobottomdental.com/orthodontics.html

[4] On3DPrinting – http://on3dprinting.com/tag/invisalign/

I found this post really interesting. I was thinking through how slowly medical/dental professionals are to adapt to change (hence Invsalign’s decision to focus on current prescriber sales growth vs. recruiting new orthodontists to the product), and wonder if there is a chance to target students in dental school. Sales reps in biopharma do this with physicians in their residency programs, and that way the docs start out familiar with the product vs. needing to change their prescribing habits once their practice is established.

I am unfamiliar with how IP protection/patents work in this space, but assuming the patent expires 20 years after filing (as it does with pharmaceuticals), I wonder what the competitive reaction will be once other firms are allowed to enter. Does Invisalign have a major advantage as the first mover here, or are insurance companies and/or orthodontists more sensitive to price? Will Invisalign be able to maintain the manufacturing advantage it has developed, or will new entrants be able to replicate this strategy?

Great post. I particularly like their move to partner with 3D systems and maybe that was the only choice to control costs.

I have a similar question with Maggie in that I am curious about how Invisalign would protect its IP – what specifically is it protecting: the modeling facility that “maps” teeth movement, the 3D manufacturing facility of Invisalign, or something more specific?

Also, suppose the next 2-week retainer is too aggressive for the patient (i.e. the retainer based on a shape that overestimated the shift of patient’s teeth). What would the orthodontist do with that retainer, and would he or she require the patient to come back to the orthodontist for a special check up? I ask this because this could cost both the orthodontist time (seeing the patient), resources (throw out the retainer) and the patient money (seeing the orthodontist and paying for it). What operational, or sales, strategy has Invisalign employed to address this potential issue?

Thanks!