Hunting in the Zoo: How Boeing’s plead for protectionism handed Airbus a spectacular opportunity to strike back

After a complaint from Boeing, the Department of Commerce imposed a 300% import tariff on Canadian aircraft manufacturer Bombardier’s brand-new C-Series aircraft, effectively shutting them out of the U.S. market. Bombardier’s response? To partner up with Airbus and produce the same planes in Airbus’s facilities in the U.S. Now Boeing finds itself fighting two fully coordinated adversaries in different fronts, and Airbus is preparing itself for a very promising war of attrition.

It is hard to argue that Aerospace is a source for pride and conflict for many nations, especially those who have competitive national aircraft manufacturers. As it stands today, two large manufacturers compete in the Wide Body and Narrow Body commercial aircraft segments: America’s Boeing and Europe’s Airbus [1].

The struggle for aircraft supremacy has led to government support for its national manufacturers (usually in regulation and subsidies) [2]. Public opinion drives support for these policies as a source for jobs, geopolitical power and national pride. However, these benefits are relevant as long as each company can put their planes in the hangars of their true customers, the airline carriers.

The airline carriers, in turn, are eager to find great deals in the purchasing of airplanes. It is not surprising, then, that the manufacturers often scramble for the most attractive airlines with the most passenger traffic. In particular, Airbus has been trying for some time now to take a swing at Boeing in the latter’s most precious market: the domestic and international U.S.-based carriers. This has been beneficial for such carriers as Delta Air Lines, who has access to Airbus’s aircraft at very attractive discounts [3], and of course for the passengers, since competition between manufacturers drives costs for the airlines down and, in turn, to lower ticket prices for all.

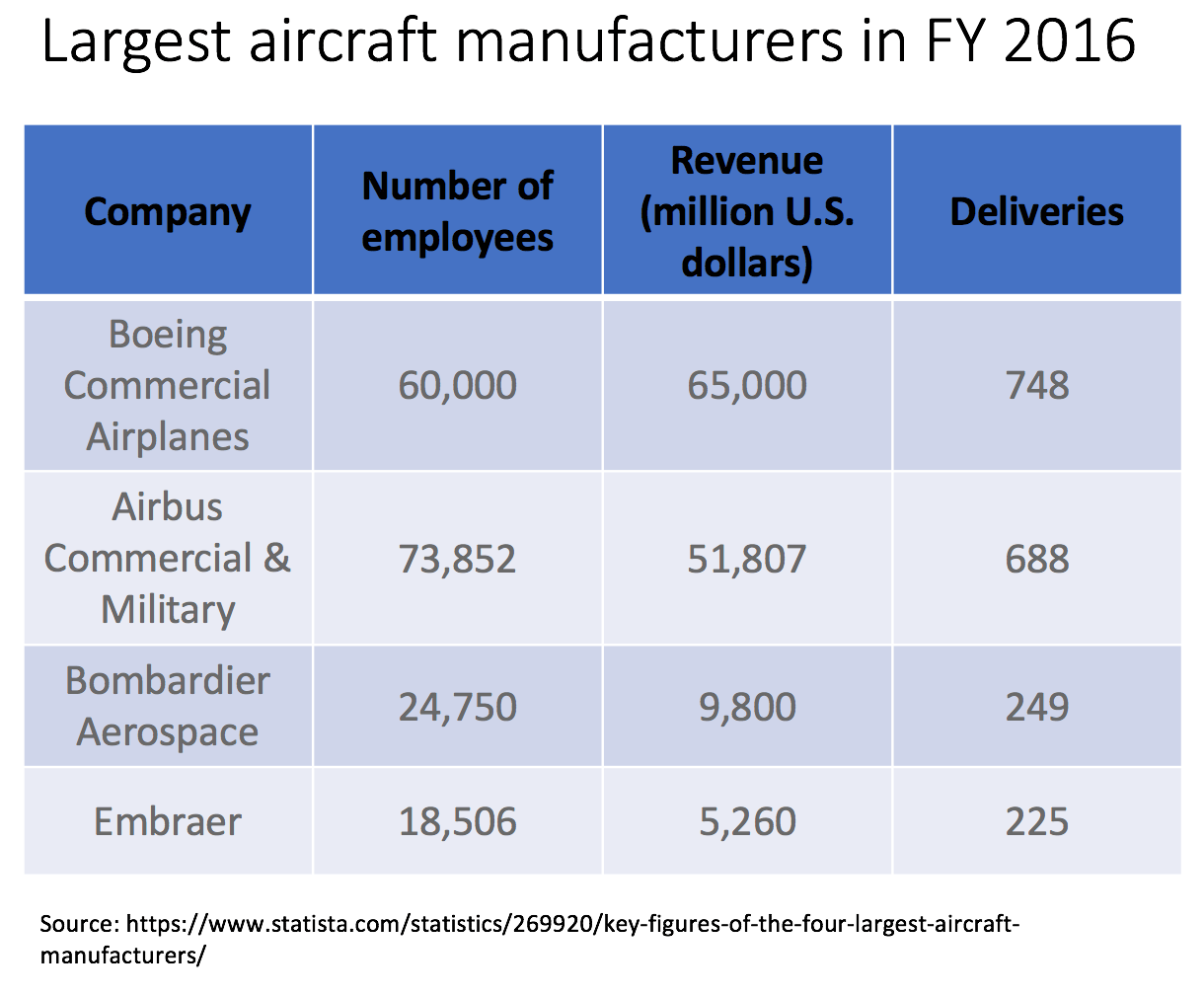

But Boeing and Airbus do not account for the whole market. Smaller companies such as Brazil’s Embraer or Canada’s Bombardier produce smaller planes, meant for shorter or lower-demand routes. These companies have been successful in their segments and did not pose a threat to Boeing or Airbus, which is why these two classes have coexisted without conflict. This all seems to have changed with Bombardier’s C-Series.

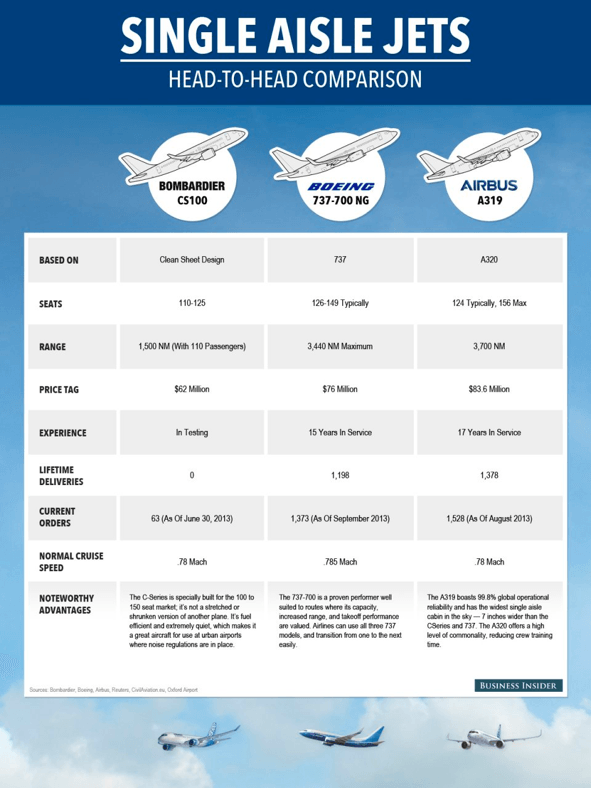

Bombardier has recently innovated with a new class of aircraft, a plane whose size is just below Boeing’s smaller Narrow Body airplanes, but with a potentially higher efficiency. While it is debatable whether this aircraft class really is that much of a threat [4] Boeing certainly took the action seriously as a direct challenge towards their authority in one of their largest and most profitable segments.

Bombardier has recently innovated with a new class of aircraft, a plane whose size is just below Boeing’s smaller Narrow Body airplanes, but with a potentially higher efficiency. While it is debatable whether this aircraft class really is that much of a threat [4] Boeing certainly took the action seriously as a direct challenge towards their authority in one of their largest and most profitable segments.

To make matters worse, Bombardier struck a deal with Delta to allegedly sell to them 75 C-Series airplanes at the abysmally low-price tag of U$S 20 Million apiece, a fraction of the U$S 60-80 million original list price and well below the U$S 33 Million cost of production per unit [5]. That fact could have justified an accusation of dumping, with the aggravating factor that the Canadian government has provided Bombardier with significant subsidies in order to sustain the C-Series program. This would effectively mean that the Canadian government had been using taxpayer dollars to hurt an American company.

After Boeing’s complaint, the DoC imposed a 300% tariff on the C-Series imported airplanes, in an effort to restore what they saw as an unfair competition scenario. This sparked all sorts of reactions from both the Canadian and U.S. presidents, with the potential fallout of the Canadian government cancelling a purchase of Boeing’s F-18 fighter jets [6]. The implications of this tariff could be disastrous for the international legal frameworks that protect expensive investments.

But, in a spectacular turn of events, Bombardier and Airbus found a different solution that would create synergies between them and put Boeing under serious competitive pressure: Bombardier ‘sold’ a 50.1% stake on the C-Series program to Airbus for free [7]. Bombardier is now allowed to produce them in Airbus’s facilities in Alabama (which, as the time of this writing, is a constituent State not subject to import tariffs) as well as take advantage of Airbus’s superiority for marketing and sales, while Airbus can add a new fully developed airplane series to its product portfolio without having had to incur any R&D expense or financial/operational risk. Sounds like the start of a long-term and fruitful relationship, and it surely means trouble for Boeing, a company which now finds itself in the defensive after attempting to utilize the law to compensate for its insecurities in its products. My personal advice for Boeing would be (i) to continue putting pressure on the regulators until the competitor’s selling price including tariffs or fines exceeds costs, (ii) reintroduce smaller versions of the 737 which could compete in the C-Series’s segment, and (iii) evaluate a partnership with Embraer and innovate with a competitive offering.

The question still remains open on how the U.S. government will react to this: will it will defend a U.S. company against a foreign company producing in the U.S.?

Questions:

Imagine you are an executive of Airbus. How would you defend your position in a conversation with DoC officials? Now, put yourself in Boeing’s shoes.

What actions can multinational corporations take to protect themselves from these situations, especially taking into account the innovation funnel?

(Word count: 798)

[4] http://www.businessinsider.com/bombardier-cseries-vs-boeing-and-airbus-2013-10

[7] https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2017/10/16/bombardier-airbus-deal-airliner-could-help-avert-massive-tariffs/JxEMTghOQTlrID6DkxhLvN/story.html

Very interesting read! I find it particularly interesting that Airbus does not see Bombardier’s C-series program entrance as a threat. As you write, given their 50.1% stake on the C-Series program, Airbus is essentially handed a tested aircraft blueprint for free. However, what happens if Delta finds Bombardier’s aircrafts superior to those of Airbus? Could Bombardier then potentially start to steal market share from Airbus in its home market, Europe, outside of the production licensing agreement between Bombardier and Airbus? I guess Airbus must be very confident in their aircraft’s superiority to Bombardier or be extremely eager to enter the US market.

I thought this was a fascinating read regarding the game theory of protectionist policies. If I am an executive of Airbus, I can easily defend my argument by stating that I am now producing planes in the United States and providing for US jobs. If I am Boeing, it is difficult for me to respond given the DoC responded to my lobbying efforts. However, I could try to make the argument that the Bombardier and Airbus partnership is creating anti-trust issues, but this is a difficult argument given the lack of US based competition in airplane manufacturing.

Dear Petrosian, clearly you believe in the power of a strong defense. I would, however, argue that in this scenario defense alone will not suffice. The DoC is unlikely to sustain a protectionist position when that protectionism undermines manufacturing jobs in Alabama. The American government loves Seattle manufacturing. The American government loves Alabaman manufacturing even more. The continued improvement of the 737’s efficiency is the best long-term response to the CSeries should it begin production in Alabama.

This is a very well written piece and fascinating topic!

As Steve mentioned, I wouldn’t be too worried if I was Airbus. As a company creating jobs in the US and growing relationships with local carriers which are always under serious cost pressure, it would be hard for the DoC to take steps that would be unfavorable to Airbus. On the other hand, Boeing will certainly have a hard time defending itself and asking the regulators to step in preferable policies time and again. It will only get harder for Boeing if it continues down the path of hiding behind the protectionist policies and hiding behind regulations.

In a broader context, considering the fact that in principle companies have been and should be rewarded for innovation and competitive advantages they build, there is certainly a growing threat of isolationism challenging this principle. I can only speculate that companies would have two options ahead of them. First, to take their innovation game to the next level to build expertise that is hard for other players to replicate in local markets. Or, as done by Bombardier, actively pursue the path of developing local partnerships and part with a share of their bottom line to be able to access overseas markets.

Thanks for sharing. Overall, I have a couple of thoughts.

The first is really understand why the tariffs were implemented in the United States. If the 300% tariffs was imposed because of Canadian government subsidies, then the U.S. response made complete sense. In fact, I would argue that Bombardier’s strategy to shift production to Alabama via a partnership with Airbus merits further regulatory scrutiny as the company is violating the spirit of the US enforcement action against the Canadian subsidies (although the US can gain comfort from increased jobs and production in Alabama). I would therefore add the question: Why can Airbus play by the rules, but Bombardier can’t?

Furthermore, while I see the benefit to Airbus and Bombardier of their joint venture, I see this as an anti-competitive move for customers. With only 4 world suppliers of airplanes, a combined Airbus and Bombardier venture undermines the value of even having additional competitors.

This is a very interesting article about one of my favorite topics – the manufacture and sale of commercial aircraft. I would like to highlight two addition pieces of context that help illustrate why Bombardier is willing to price below cost and why Airbus was so eager to jump at the partnership opportunity with the Canadian manufacturer.

Boeing and Airbus have been at war with one another for over 20 years regarding government subsidies. In fact, Boeing dedicates a page on its website to educating consumers and investors on what it calls “illegal government subsidies” provided to Airbus by various government agencies in Europe. (http://www.boeing.com/company/key-orgs/government-operations/wto.page) Boeing alleges that these subsidies have provided Airbus with a substantial advantage in the commercial aviation market, as evidence by Airbus’ quick ascension to 50% market share. It is unsurprising, then, that Boeing reacted aggressively in pursuing action against Bombardier when they entered the US market with their C-series aircraft. It is even more unsurprising that Airbus, who disputes Boeing’s claims of wrongdoing, jumped at an opportunity to gain footing against the Seattle-based giant in the US market.

However, another macrotrend in aviation is at play here that may at first appear less significant, but has very real competitive implications for Boeing and Airbus alike; the move to regional jets. According to Patrick Smith, author of Cockpit Confidential, US airlines began shifting many of their domestic routes from larger narrow- or wide-bodied aircrafts (such as the Boeing 737, 757, or Airbus A320) to regional jets (such as the Embraer 145 or the Bombardier CRJ-700) as a means to provide greater customer choice in departure times and gain advantage over competition. This resulted in a growing market for regional jets in the United States. This trend, coupled with the projected failure of super-jumbos (the Boeing 747 is largely being retired by US airlines, and many OUS carriers are backing out of leasing agreements for the Airbus A380), should be of concern to Boeing. I agree with your suggestion that Boeing should focus less on government intervention, and more on creating a product line that meets the needs of their customers, either through in-house development or a partnership with regional jet manufacturers.