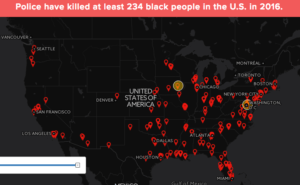

How Many People Are Killed by Police?

In an age of data, why is it so hard to find out how many people of color have been killed by police?

Incidents of police killing unarmed people of color have made national headlines, leading to the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement. The magnitude of these incidents have been heightened by pictures and videos shared on social media. Yet despite the public’s interest in this topic, until recently little good data was available to study the prevalence of police violence in America. Over the past couple years there has been a renewed focus on data and technology that aims to educate, provide transparency, and even warn about potential police abuses in the United States.

The model that was supposed to establish a reporting program for data quantifying the occurrence of police violence against civilians was established in the 1990s. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (“Crime Act”) mandated that the Justice Department gather data about the “use of excessive force by law enforcement officers” and include it in an annual report made public.[i] The method in which the Justice Department was to collect data and the factors they would comprise, however, were not stated in the Crime Act.[ii] Due to this ambiguity (and other political factors) this report has not been consistently issued.[iii]

One of the main problems in publishing this data is that the responsibility for collecting it is split among local departments. There are approximately 18,000 law enforcement agencies throughout the country, most of which contain fewer than 25 officers.[iv] Furthermore, to the extent a department does have the resources to report such data, there is no standard methodology or required inputs that the Justice Department requires. Factors such as the race of the victim, the circumstances in which an incident occurred, and the level of force are not always recorded.[v]

Non-governmental groups including media outlets in recent years have attempted to supplement this model by aggregating both public and private data on police violence:

www.mappingpoliceviolence.com attempts to aggregate data from a variety of sources

- UCLA’s Center for Policing Equity has established the National Justice Database to track national policing behavior including stops and use of force. To date, more than 40 police departments participate covering over 25% of Americans.[vi]

- Websites like www.mappingpoliceviolence.com and www.checkthepolice.org aggregate data from a variety of sources to publicize the magnitude of the problem. These sites merge incomplete agency data with other sources like Facebook, local obituaries, and even previous arrest records to compile racial breakdowns in violent confrontations with police.[vii] [viii]

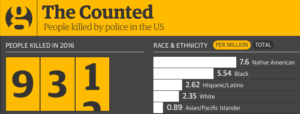

- In 2015, both The Guardian and The Washington Post began to publish data on police killings. Yet these two news outlets show variability in their findings. In 2016 through the date of this note, The Washington Post reported 843 people killed by police while the Guardian reported 931. [ix] [x]

The Washington Post (left) and the Guardian (right) show different numbers of police killings in 2016.

While the efforts of these organizations have helped, there is still a public need for accurate statistics. Trying to enhance the broken model established in the Crime Act, the Obama Administration launched the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, leading to the Police Data Initiative (“PDI”).[xi] The PDI will use technology and enhanced data gathering techniques to increase transparency into policing across the nation. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the PDI aims to establish an “early warning system to identify problems, increase internal accountability, and decrease inappropriate use of force.” Some of the goals of the PDI include:

- Releasing previously privately held department data

- Creating a public safety open data portal that will serve as a central database and clearinghouse for police data

- Building new software and technology with private institutions to be distributed to local departments

- Developing an “Open Data Playbook” for agencies to use to review standard best practices and case studies

- Further research into the use and benefits of cameras in cars and body cameras on police to increase transparency.[xii]

Thus far the PDI covers 53 jurisdictions encompassing 41 million people and has produced over 90 datasets for public consumption.[xiii]

President Obama speaking to the press after a meeting with the Task Force on 21st Century Policing

Unfortunately, while the PDI is a good step in fixing the current model of reporting and publishing statistics on police violence against civilians, it is not yet sufficient. Because it was launched through a task force and not by an act of Congress, there is no assurance it will continue through future administrations. A congressional attempt to help with this known as the PRIDE Act has been stalled in committee for over a year and would just shift the burden for reporting data to the states.[xiv]

It is a shame that in a world of data, statistics on how often people of color are killed by police are not easily found. Digital technology from the PDI and work by non-governmental organizations are good starts, but without full federal support, they face challenges in accessibility and accuracy. With the current state of congressional gridlock, it does not seem likely to be fixed anytime soon.

(786 words)

[i] https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ndcopuof.pdf

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/10/the-police-are-still-out-of-control-112160_Page2.html#.WC4nuxIrLeQ

[iv] http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/ferguson-michael-brown-measuring-police-killings/

[v] http://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/podcast-we-still-rely-on-volunteers-to-tally-the-victims-of-police-violence/ (and the associated podcast).

[vi] http://policingequity.org/national-justice-database/

[vii] http://mappingpoliceviolence.org/aboutthedata/

[viii] http://www.checkthepolice.org/#project

[ix] https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/how-the-washington-post-is-examining-police-shootings-in-the-united-states/2016/07/07/d9c52238-43ad-11e6-8856-f26de2537a9d_story.html

[x] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/about-the-counted

[xi] https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/04/22/fact-sheet-white-house-police-data-initiative-highlights-new-commitments

[xii] https://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2015/05/18/launching-police-data-initiative

[xiii] https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2016/04/22/fact-sheet-white-house-police-data-initiative-highlights-new-commitments

[xiv] https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/114/s1476/summary

Very important post – thanks for sharing. You highlighted three important challenges of using data in the public sector that make it fundamentally different from the private sector: (1) dispersion of responsibility, (2) lack of political animus, and (3) term limits for elected officials. This is especially true at the national level — cities are typically much better at providing this type of data given the relatively limited number of stakeholders and centralized police administration.

Another key aspect at play is the lack of incentive to report these statistics on the part of the police forces in question. I’m not suggesting any actors are intentionally misleading the public (although I can’t rule that out either), but it’s quite possible that they view investing in developing tools to provide accurate reporting as a departure from their “operating model,” e.g. that it doesn’t help them do their jobs better. Some even might view the goals of Obama’s Task Force as presidential overreach and an expansion of the regulatory state. Police forces might be further concerned about the misinterpretation or misuse of data.

I think a key next step for those of us who care deeply about the way policing has evolved over time is to work to demonstrate the value of data in this field to all parties — citizens, government, and police. Transparency for transparency’s sake is an effective public argument, but not one that will motivate fundamental behavior change on the part of police. If, for example, policy analysts could demonstrate a link between data collection (and meaningful use within the police department) and officer job satisfaction due to improved police-community relationships, we might see an uptick in reporting.

This is crazy, thanks so much for sharing. What a messed up system.

Estonia has a pretty cool system that the US could potentially learn from, though I guess it would take some time to get to that point…! Their centralized database allows them to e.g. scan the license plate of a car they have just pulled over and immediately get information on owner, family members, registered weapons, prior offenses, etc. Though some of that information could certainly also be dangerous if over-generalized on, it could also be helpful to the vast majority who are stereotyped for no reason other than their race by giving police additional context.

To build on Jason’s point, I think the best way to demonstrate the value of data to officers is to use it to help them prevent violence. Today, most major PDs use early warning systems to flag officers who might be at risk for committing violence. But these systems aren’t particularly sophisticated (often relying on supervisor’s recommendations) and get mixed reviews on effectiveness. However, by collecting better data from departments, data scientists can more accurately predict which officers are at risk of violence and divert them into training or counseling. You can read more about these efforts here: http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/we-now-have-algorithms-to-predict-police-misconduct/.

Ultimately, efforts to promote transparency in policing are often stymied by police unions, which are notorious for fighting any innovation that risks members’ job security. Since they are not going away any time soon, we should continue to demand specific changes (such as body cameras) – while progress may be painfully slow, the trend is clearly toward more transparency.

Ari, thanks so much for sharing on this important topic.

It is horrifying to me to think that in a time when we have an abundance of data on so many asinine topics for commercial purposes, we cannot get a straight story on an issue as important as how many people are killed by our government each year. I think Jason raises a very interesting point on figuring out how to make this data useful to police departments by showing how it might improve their day-to-day through better community relations. I think its a nice idea, but I do not think its acceptable that we feel the need to provide incentives for such basic and critical reporting that should be a minimum expectation of our public officials.

I would be curious to understand what private sector solutions we can create to streamline data recording and push onto police departments via legislation. I posted for this assignment about the ways Palantir is using all disparate data to help police departments eradicate crime, perhaps they could use the same (traffic / police cruiser / body) cameras to hold police accountable? I read an interesting post about IOT, perhaps police weapons of the future could automatically generate a report when discharged to prompt involved officers to enter necessary data?