Grocery Delivery: 2nd Time’s the Charm? Instacart vs. Webvan

Can the second iteration of the digitalization of the grocery find a different outcome in the form of Instacart?

A Primer on the Digitalization of the Grocery Store

The year is 1996, and the internet was in its infancy. At the time, just 36 million people worldwide (compared to the 3.6 billion people today) had access to the internet, and internet participation was growing at >100%/year1. For a number of daring business people, the environment of rapid internet adoption meant one thing: disruption to traditional business models.

One of the most salient examples of the zeitgeist was the desire to disrupt brick & mortar businesses. Companies like Pets.com, Books-a-Million, Kozmo.com, and Boo.com, while now long-forgotten, had the backing of millions of dollars (and the valuation of billions of dollars), all with the hope of killing off the retail store and ushering in a new digital retail experience.

It seems fitting that the grocery industry also saw its share of iconoclasts. The internet seemed to represent an end to check-out lines, ripped shopping bags, and squeaky grocery carts. With a click of a button, companies promised to move the grocery experience to the digital age. And with a $1 trillion market (between grocery and convenience shopping) up for grabs, the prize for the winner was too big to ignore2.

The Rise of Webvan

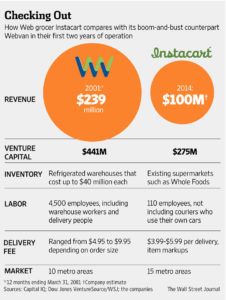

Webvan, founded in 1996 by Louis Borders (founder of Borders bookstore), seemed to be perfectly positioned to digitalize the grocery world. The market agreed, as Webvan took on $396 million in funding, at a valuation of over $4.8 billion3.

Its value proposition seemed intuitive: Instead of walking or driving to the nearest grocery store to pick up groceries, users would instead use Webvan’s web portal from the comfort of their own homes, place their orders online, and pay with their credit cards. Groceries were then delivered in brightly colored plastic boxes to the users’ homes. For a premium, customers were saving time and effort on a major part of their day to day life. The internet heralded a totally new way for customers to make their regular transactions, and Webvan seemed to be a game-changer.

The Decline of Webvan

While there was excitement about Webvan, ultimately the company spent incredible amounts of money while not recouping enough in sales to make the venture profitable.

Because Webvan decided to build out its own infrastructure (including warehouses across the country and a nation-wide fleet of vans), its capital expenditures were enormous.

So despite Webvan’s novel use of technology to revolutionize the shopper experience, Webvan kept one very heavy foot squarely in the non-digitized world of grocery logistics.

In just 4 years, the financial rollercoaster that began with over $300 million in funding ended with Webvan’s declaration of bankruptcy.

Instacart: Webvan 2.0?

So now, 15 years after the demise of Webvan, a new player in the grocery digitalization space has come to take its place. Two key questions immediately arise: 1. What makes Instacart different than Webvan? 2. Will these differences lead to a different outcome?

Like Webvan, Instacart provides users a web portal (though now with the advent of smartphones, Instacart is heavily focused on the mobile experience) through which grocery shoppers can place their orders. And again, like Webvan, Instacart will deliver groceries right to shoppers’ doorsteps.

Instacart, however, has one key difference that gives investors hope that Instacart won’t just be Webvan 2.0. Instacart leverages the “sharing economy” that companies like Uber and Task Rabbit have popularized. Instead of Instacart-owned vans delivering goods from Instacart-owned warehouses, Instacart instead enlists the help of contractors who use their own cars to drive to local grocery stores to shop for the Instacart users.

The outcome is millions of dollars worth of capital expenditure savings for Instacart compared to Webvan.

So far, Instacart has raised $264 million in funding at a $2 billion valuation4.

Digitalization: Technology vs. Timing

Ultimately, we still don’t know whether the grocery industry is going to be revolutionized by digitalization. It remains to be seen whether Instacart becomes a mainstay for a large portion of grocery consumers; however, it’s not a stretch to see why consumers and investors are hoping it works.

But we still cannot forget that digitalization alone cannot revolutionize businesses easily: perhaps Instacart has figured out a way to not only improve the shopper experience, but also to cheapen the logistics behind grocery shopping. Or perhaps, like Webvan, Instacart will come across another impasse that its digitalization efforts won’t be able to easily overcome, and we’ll have to wait another 15 years before we find another service that really brings home the bacon.

Word Count: 758

Sources:

- “Today’s road to e-Commerce and Global Trade Internet Technology Reports,” Internet Growth Statistics, internetworldstats.com/emarketing.htm

- “The Next Big Thing You Missed: Online Grocery Shopping Is Back, and This Time It’ll Work,” Wired Magazine , Febuary 2014, https://www.wired.com/2014/02/next-big-thing-missed-future-groceries-really-online/

- “10 Big Dot Com Busts,” CNN, March 2010, http://money.cnn.com/galleries/2010/technology/1003/gallery.dot_com_busts/2.html

- “America’s Most Promising Company: Instacart, The $2 Billion Grocery Delivery App,” Forbes, January 2015, http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2015/01/21/americas-most-promising-company-instacart-the-2-billion-grocery-delivery-app/#76e931254858

I’d add that another difference between Instacart and Webvan are their partnerships with existing grocery stores, like Whole Foods. From my understanding, Webvan attempted to build out their own distribution centers and didn’t leverage the existing infrastructure of grocery stores – whereas Instacart purely shops and delivers for the customer at existing grocery store chains.

This strategy for Instacart may limit their growth in the near term as they are not partnered with grocery store chains that reach all geographies, but does allow them to run an asset-lite model, unlike Webvan.

Thanks, Brian. I agree with Margaret that having an asset-lite model is the only way to succeed in this space. I have used FreshDirect, a similar company that only serves the New York metropolitan area. FreshDirect has taken a much more conservative strategy, having been around since 1999 without expanding beyond their base locations. I don’t really see how FreshDirect makes money from anyone except high income people who are willing to pay huge markups on certain produce. Some of FreshDirect’s products are reasonably priced, and the convenience of the delivery made it worth my while to order these particular items. I just don’t see the margins on these products making it profitable to cover the enormous overhead from delivery in NYC, especially since they frequently offer free shipping and will have to keep much of the produce refrigerated or frozen. This is not cheap or efficient.

I don’t see this business model ever succeeding except if they charge a large delivery fee or have huge markups on their products. In this case, they will have to cater to wealthy, price insensitive individuals to whom convenience is the only parameter.

Thanks Brian. My views echo some of what Zach stated above. I think Instacart may be more successful than Webvan in a relatively small market of wealthy urban dwellers. It seems to me that Instacart will be most successful in places where grocery delivery has traditionally thrived, but unless they can drive delivery prices down substantially, I’m not sure that they’ll lure a significant amount of new users to grocery delivery.

Specifically, I would expect that many consumers who purchase groceries on a regular basis are looking for a less expensive alternative to eating out, making the additional fees charged for grocery delivery unattractive. Another concern would be the poor economics of grocery delivery in non-urban areas, making the value proposition even worse for a large swath of suburban consumers.

What do you see as the major opportunities for Instacart to gain new users, aside from those who already use traditional grocery delivery?

Thanks Brian! Your assessment of the strengths of Instacart compared to Webvan make a lot of sense. One question that I have regarding the future viability of Instacart is how existing grocery stores view Instacart – as a collaborator or a competitor? It seems like Instacart has been able to partner with grocery stores to date; however, I’m surprised that some grocery stores have not tried to prevent Instacart from shopping for groceries in their stores and then charging a premium to customers that the grocery store then doesn’t get any part of, when it seems like they are bearing most, if not all, of the costs in this scenario. Additionally, even if grocery stores do not see Instacart as detracting from their revenues if it still brings somebody into their grocery store to buy goods, have they tried to prevent Instacart from partnering with other grocery stores? It would seem to be in the grocery store partner’s best interest to only have Instacart shopping for goods from their store, and not allowing Instacart customers to shop at a rival grocery chain.