From Russia With(out) Love: Russian Rockets & American Aerospace

How Ongoing Russian Sanctions and Political Isolationism Threaten ULA’s Supply Chain Within the US Space Industry

Word Count: 796

Risks & Actions

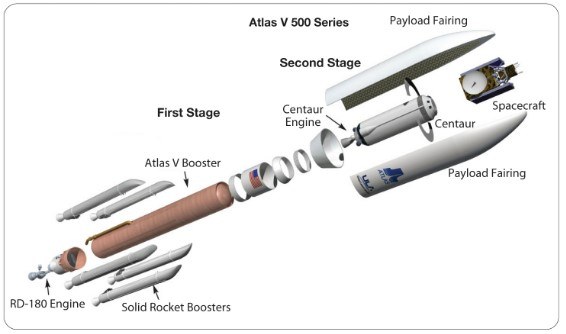

Since the 2014 imposition of US Sanctions on Russian imports in reaction to the invasion of Ukraine[1], United Launch Alliance (ULA) has required an exception to these sanctions to source a critical component of its workhorse Atlas V rocket, Russian-built RD-180 engines.

As tensions remain high between the two countries, the following risks are key to ULA’s continued existence:

- ULA’s supply chain relies on one rocket engine with no domestically produced alternatives, currently.

- Domestically produced alternatives will not be available until 2019 at the earliest.

- Future isolationism and political events could prevent ULA’s from sourcing engines if it loses its sanction exemption status.

- Domestically- and vertically-integrated competitors will increase both political and cost pressure on ULA.

In response to these threats, ULA must consider the following actions:

- Build closer relationships with both Blue Origin and Aerojet Rocketdyne as equally alternative suppliers.

OR

- Purchase/Merge to achieve in-house rocket engine production capabilities.

AND

- Immediately identify and add in-house capability for any other internationally produced components.

ULA’s Current Environment

Russian Sourcing & Sanctions

Beginning in 2014 and until this essay’s publishing, Russia has been under multinational sanctions[3]. In response, Russian officials in 2014 threatened to ban the sale of RD-180 engines to the US [4]. While these threats were not realized[5], every US National Defense Authorization act passed by the House of Representatives since 2014 has contained an exception provision for the purchase of RD-180 rockets from Russia[6]. This has caused considerable controversy from both lawmakers such as Senator John McCain[7] and industry competitors such as SpaceX[8].

Competitive Supply Chains

The current Space Vehicle industry is increasingly competitive due to private sector companies such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic entering the industry to drastically reduce the price of launches via reusable launch vehicles (RLVs) in contrast to ULA’s currently expendable launch vehicles (ELVs). When these competitors entered, they created their own supply chains emphasizing vertical integration and domestic production. Because of this, both main competitors SpaceX and Blue Origin already develop their rockets domestically[9],[10] and are therefore under no such supply chain pressure.

SpaceX has already completed several launches to the International Space Station (ISS) delivering supplies using its Falcon 9 RLV. While the Falcon 9 RLV does not have quite the same capabilities or capacities as ULA’s Atlas V, SpaceX is targeting to launch its new Falcon Heavy RLV in December 2017[11] which would easily exceed Atlas V’s capabilities[12],[13]. Additionally, Blue Origin is developing its own RLV “New Glenn” which it believes it can launch by 2020 and will also exceed Atlas V capabilities[14]. ULA’s market power for launches will be greatly diminished when these competitors begin launching.

ULA’s Current Mitigation Steps

Short-Term: Political Lobbying

Primarily, ULA has used its large market share and relative monopoly in the Space Launch Industry to lobby successfully for exceptions on rocket engines in sanctions on Russia. ULA has previously cited national security concerns if there is a gap in US military launch capabilities since as early as 2010.[15] Additionally, within the same presentation, ULA recognized both the cultural, ethical, and export issues which would result from the US/Russian partnership. [16] Nonetheless, ULA has been successful at fending off competitive pressures on the government to remove the sanction exception for the RD-180.[17] Time will only tell if this tactic will continue to be successful as SpaceX and Blue Origin show they have the ability to compete for government contracts. [18]

Mid-/Long-Term: Domestic Suppliers

Blue Origin’s BE-4

Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1

In addition to the BE-4, Aerojet is developing its own engine, the AR1, which it believes it can produce a flight ready engine by 2019.[23] However, the engine is currently considered a backup to Blue Origin’s BE-4. This is a risky plan for ULA, but they are effectively betting on working with the more capitalized company, at the risk of longer-term profitability.[24]

Remaining Questions

- Which engine will ULA ultimately decide on and what competitive impact will there be from their selection?

- How will Aerojet view a merger attempt, given ULA rejected a previous buyout offer from Aerojet in 2015?

Sources:

[1]: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, HR4435, 113th Cong., Congressional Record 160. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4435, accessed November 2017.

[2]: ULA, “Atlas V.” http://www.ulalaunch.com/Products_AtlasV.aspx, accessed November 2017.

[3]: Council Decision 2014/145/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine, 2014. OJ L78/16. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2014:078:0016:0021:EN:PDF, accessed November 2017.

[4]: “Russia responds to US sanctions over Ukraine,” ITV, May 13, 2014, http://www.itv.com/news/update/2014-05-13/russia-responds-to-us-sanctions-over-ukraine/, accessed November 2017.

[5]: Doug Cameron, “Russia Sanctions Aren’t Rocket Science, Except When They Are,” Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2014. https://blogs.wsj.com/corporate-intelligence/2014/07/21/russia-sanctions-arent-rocket-science-except-when-they-are/, accessed November 2017.

[6]: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015, HR4435, 113th Cong., Congressional Record 160. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/4435, accessed November 2017.

[7]: Andy Pasztor, “McCain Compromises on Russian Engines for Pentagon’s Space Launches,” June 14, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/mccain-compromises-on-russian-engines-for-pentagons-space-launches-1465944194, accessed November 2017.

[8]: Loren Thompson, “Why SpaceX Lost Its Bid To Ban Russian Rocket Engines,” July 7, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lorenthompson/2016/07/07/why-spacex-lost-its-bid-to-ban-russian-rocket-engine-debate/, accessed November 2017.

[9]: SpaceX, “About SpaceX.” http://www.spacex.com/about, accessed November 2017.

[10]: Blue Origin, “BLUE ORIGIN DEBUTS THE AMERICAN-MADE BE-3 LIQUID HYDROGEN ROCKET ENGINE.” https://www.blueorigin.com/news/news/blue-origin-debuts-the-american-made-be-3-liquid-hydrogen-rocket-engine, accessed November 2017.

[11]: Kennedy Space Center, “Rocket Launches,” https://www.kennedyspacecenter.com/launches-and-events/events-calendar/2017/december/rocket-launch-spacex-falcon-heavy, accessed November 2017.

[12]: SpaceX, “Capabilities & Services,” http://www.spacex.com/about/capabilities, accessed November 2017.

[13]: ULA, “Atlas V.” http://www.ulalaunch.com/Products_AtlasV.aspx, accessed November 2017.

[14]: Nicholas St. Fleur, “Jeff Bezos Says He Is Selling $1 Billion a Year in Amazon Stock to Finance Race to Space,” New York Times, April 5, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/science/blue-origin-rocket-jeff-bezos-amazon-stock.html.

[15]: Gregory J. Pech, “Russian RD-180 Rocket Engine for Atlas V Launch Vehicle,” February 10, 2010, https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/427652main_PMC_2010_Pech_Russian.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[16]: Gregory J. Pech, “Russian RD-180 Rocket Engine for Atlas V Launch Vehicle,” February 10, 2010, https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/427652main_PMC_2010_Pech_Russian.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[17]: Loren Thompson, “Why SpaceX Lost Its Bid To Ban Russian Rocket Engines,” July 7, 2016, https://www.forbes.com/sites/lorenthompson/2016/07/07/why-spacex-lost-its-bid-to-ban-russian-rocket-engine-debate/, accessed November 2017.

[18]: Eric Berger, “Air Force budget reveals how much SpaceX undercuts launch prices,” June 15, 2017, https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/06/air-force-budget-reveals-how-much-spacex-undercuts-launch-prices/, accessed November 2017.

[19]: Blue Origin, “BE-4,” https://www.blueorigin.com/be4, accessed November 2017.

[20]: Stephen Clark, “ULA chief says Blue Origin in driver’s seat for Vulcan engine deal,” April 18, 2017, https://spaceflightnow.com/2017/04/18/ula-chief-says-blue-origin-in-drivers-seat-for-vulcan-engine-deal/, accessed November 2017.

[21]: Mohamed M. Ragab et al. “Launch Vehicle Recovery and Reuse,” ULA, http://www.ulalaunch.com/uploads/docs/Published_Papers/Supporting_Technologies/LV_Recovery_and_Reuse_AIAASpace_2015.pdf, accessed November 2017.

[22]: Eric Berger, “Blue Origin releases details of its monster orbital rocket,” March 7, 2017, https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/03/blue-origin-releases-details-of-its-monster-orbital-rocket/, accessed November 2017.

[23]: Aerojet Rocketdyne, “AR1,” http://www.launchar1.com/, accessed November 2017.

[24]: Clay Dillow, “Engineering Exec Departs ULA After SpaceX Comments,” Fortune, March 17, 2016, http://fortune.com/2016/03/17/ula-exec-admits-company-cant-compete/, accessed November 2017.

Ultimately, I believe that the BE-4 will become the primary engine supplied for the ULA Vulcan. Blue Origin has more recent experience developing new engines, having proven its ability to develop a throttle-able rocket engine with the flight-tested BE-3. By comparison, Aerojet Rocketdyne has not developed a new ground-up engine in over a decade. Additionally, the BE-4 using LNG for propellant, which is between 1/4 and 1/3 the cost of the RP-1 used in the AR1, adding a further recurring cost advantage to the BE-4. The AR1 is currently about two years behind the BE-4 in development schedule. Given the currently strained relationships with Russia, it would be difficult for Congress to continue approving ULA’s sanction exemptions once an American-sourced alternative is available.

By partnering with Blue Origin, ULA is effectively subsidizing a future competitor’s development efforts. Blue Origin has demonstrated it’s suborbital RLV platform with the New Shepard, and once the New Glenn is mission-ready will be able to compete directly with ULA for launch contracts. As you mentioned, the recurring cost savings from the Blue Origin RLV will put significant market pressure on ULA. Although ULA is claiming that its recoverable engine plan will bring Vulcan launch costs within range of the reusable booster concepts, it is completely untested and not ready for its first test flight until at least 2024. This gives Blue Origin 4-5 years to refine its process for restoring New Glenn 1st stage boosters (in addition to the experience the company already gains from testing New Shepard rockets), which will likely generate additional cost benefits.

ULA’s best hope is to continue to leverage their longstanding relationships with NASA and the DoD, and proven track record of handling projects relevant to national security interests. Aerojet Rocketdyne would be a natural partner for this effort, but unless the partnership can deliver on their promise of cost parity, it may be too little too late.

The escalating tensions between the US and Russia creates uncertainty in the approach and strategic direction of ULA. An interesting development that adds an additional layer of complexity is the recent indecision of the EU government on guaranteeing ArianeGroup at least five government satellites [1]. This could present an opportunity for ULA to challenge SpaceX through their partnership with Blue Origin, or at least consider European opportunities outside of Russia. This recent development makes me wonder whether the EU is moving in the direction of isolationism, or considering exploring international options for rockets?

[1] “EU Governments’ Indecision on SpaceX Challenge Seen as Threat to Ariane System’s Survival.” Space Intel Report, http://www.spaceintelreport.com/eu-governments-indecision-spacex-challenge-seen-threat-ariane-systems-survival/, accessed November 2017.

The US government has made a series of strategic decisions that have unfolded into a very difficult situation within the space industry. Space is much more than scientific exploration, I use my GPS nearly everyday and know the US military relies on intelligence that is bounced off satellites orbiting the earth. As we look back on the US government’s exodus from building launch vehicles, the US government has become beholden to the decisions of private enterprises. I find it very concerning and hilarious that in a situation of contention with the Russians that we are reliant on them for critical pieces of infrastructure that relate to our national security. It is amazing to see how interconnected the world has become and important to realize the impact of how certain isolationist policies ripple through the economy and government. Bezos and Musk, who have been driven to space by their fascination with the topic could be the unlikely winners in this problem because of their domestic production. For any industry it is vital to always have a plan B. UAL was put in a very unfortunate position where geopolitical issues interfered with their profitability and they did not have a Plan B.

Ben, this is a fascinating topic and I appreciate you sharing it. Like Austin, I’m a bit surprised that ULA has allowed its supply chain to remain so vulnerable over the past decade despite numerous indications of the deteriorating relationship between the US and Russia well before 2014. I would push back on one of Austin’s points however in that I think it was a series of tactical decisions rather than strategic decisions that led the US and ULA to this point. Despite spending more than $120 million in 1995 to develop domestic RD-180 production capability, Lockheed Martin and ULA were unable to compete with Russia’s $10 million-per-rocket production cost (https://www.thedailybeast.com/why-does-the-usa-depend-on-russian-rockets-to-get-us-into-space). The government decided it was better (and probably more politically expedient) to continue buying the cheaper rockets from Russia instead of pursuing expensive domestic alternatives. Even as recently as June of this year, the US Air Force awarded another $191 million to ULA to continue using the Atlas V with Russian-made RD-180 engines through 2019. With continued investment in ULA, I, like Rob, would expect the BE-4 to be the eventual replacement of the RD-180 and stave off threats of an Aerojet merger.

After reading this article, I thought it was informative, and also indicative of some of the short-sightedness of large successful companies. I would think that the fact that the ULA is still dependent on Russian rockets after more than a decade is a major mistake. It seems the ULA’s primary strategy to ease the political isolationism related to Russia is to keep banking on import exceptions. How can the U.S. military allow itself to be dependent on Russian rockets until 2019, at the earliest? Also, such projects may experience significant delays. It seems an intentional lack of planning on the part of ULA and the DoD where they are now in a situation where they are in a race against time to domestically develop another rocket engine before the sanctions are kept in place for Russian rockets. Can’t we work with the other countries in the mean time?

Ben, thanks for this very interesting read! I think your article perfectly highlights the irony of political conflict in the face of economic interdependency, which is particularly interesting in the context of the US/Russia space race as they have been and continue to be vocal rivals. I appreciate that the solution you present is to utilize free market incentives to boost up American space companies in order to mitigate the economic risks of political isolationism, and I wonder if conversely there will be strong enough business incentives to overcome the suffering, pain, and disadvantage caused by political isolationism. This article makes clear that the US remains in many ways completely dependent for its national security on the very agents (China, Russia particularly), that it must boost up its national security to protect itself against. Even if one solution is to outsource to American companies, those companies may also have in their best interest to export supply chain management out to these same nation-state agents with which the US has an antagonistic political relationship. Perhaps the best protectionism is to embrace the truth of economic interdependency and translate its motivations into diplomatic achievements.

Very interesting read! Its so fascinating to see US still export engine for their rockets form Russia. What I am curious about is if ULA is planning on moving toward RLV. RLVs are much more cost effective and with the current successful runs of SpaceX with RLVs , it seems to me that the market is moving towards that trend. And if in the future private companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are able to provide cheaper yet safer rockets, what would limit the US govt or Nasa from not using these companies instead of ULA. I guess what I don’t understand is, in spite of being a market leader, why has ULA not been able to develop a stronger position on RLVs.