Did Kodak Ignore the Digital Revolution?

Hopefully you don’t pick a company that I know something about – Paraphrasing Professor Shih, former Senior Vice President at Eastman Kodak Company

Kodak – A classic tale of corporate arrogance?

We all know the story. Big corporations are slow. Their old age and out of touch management only survive because inertia and economies of scale allow them to. They’re one disruptive technology away from being overthrown, not only because of their size, but because of their complacency. The classic example? The Eastman Kodak Company – a “company [that] had the nearsighted view that it was in the film business instead of the story telling business.”1 The digital transformation that helped so many businesses and industries is often credited with Kodak’s decline. Despite inventing the “first digital camera in 1975,” Kodak apparently refused to take advantage of its market leading position to pivot to digital thanks to a combination of arrogance and “blind faith” that marketing power could persuade its customers to ignore digital photography.1

Kodak’s operating model

But is that the real story? Was the market leader of film really so blind, or was the advent of digital film more disruptive to Kodak than it might seem? While digital technology was beginning to take over the industry, Kodak was forced to operate with its existing capital – production lines with high fixed costs that were optimized for large orders, not diminishing sales.2

Figure 1: Machinery used in the production of analogue film (c. 1958)3

To combat this problem, Kodak reduced its product mix – driving customers to digital even faster.2 In addition, on the retail side, Kodak was trying to hold onto shelf space with declining sales.2 Even if Kodak knew that digital would be the market leader of the near future, voicing this knowledge would only incentivize retailers to pull Kodak’s products off of the shelf faster.2 As a whole, Kodak’s operating model simply did not mesh with digital technology.

Kodak’s business model

Complex analogue film manufacturing required overhead and it required expertise – something very few companies, aside from Kodak, had.2 In contrast, digital imaging was grounded in semiconductors, a fundamentally different technology that other industries and companies focused on.2 This shift evaporated Kodak’s competitive edge and lowered the barriers of entry to the market.2

In addition, Kodak had built relationships with its retailers that depended on a mutually profitable ecosystem: customers would come to retail stores to purchase film, return to drop off the film, and then return again to pick up the finished prints.2 Of course, every return visit generated additional business for the retailer.2 The shift to digital technology eliminated this ecosystem, and with it, the inherent loyalty that retailers had to Kodak.2

Kodak’s business model revolved around its unique expertise and its relationships with retailers. Kodak’s success with digital technology did not hinge on a simple change from one set of products to another, it would have required the company to effectively start over with an entirely different business model.

End of the line

Even with these problems, Kodak continued to innovate in the digital space. For example, it introduced the Kodak Photo CD system in 1992, a “way of efficiently transferring high-quality photos from traditional cameras to personal computers,” which allowed individuals and businesses to use Photoshop to edit their images.4 However, it was not long until fundamental changes in technology and ecosystems caused Kodak to become truly obsolete. People stopped using analogue film with Kodak cameras and started taking pictures on their smartphones. Even if Kodak was fully aware of the oncoming digital transformation, it would have been hard pressed to move from an analogue film business with 70% market share to a much smaller player in the digital smartphone world.5

The bigger “picture” – next steps

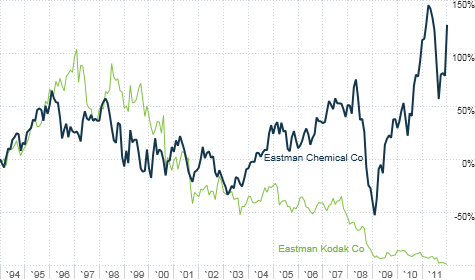

Digital technology added value to the film and picture industry in many ways. Unfortunately for Kodak, its market leading position did not earn it a piece of that value. In late 1993, in an attempt to focus on film, Kodak spun off Eastman Chemical.6 Eastman proceeded to outpace Kodak and increase in value over the next two decades.

Figure 2: Eastman Chemical and Kodak’s growth over time6

In the end, Kodak shouldn’t have thought of itself as a film business and it shouldn’t have thought of itself as a story telling business; it should have thought of itself as a niche chemistry business. Of course, acting on this would have required abandoning a market leading position in the film industry that Kodak was known for – a tough sell for anyone, even with digital disruption on the horizon. Kodak still exists, it still serves some film markets, and it’s still struggling.7 Going forward, the company needs to re-examine its core capacities and expertise to identify markets where it could still have a competitive edge. It needs to re-construct its operating model and business model around a market that values its competitive advantages. Unfortunately for Kodak, that market is no longer commoditized imaging.

(799 words)

[1] Avi, D. “Kodak Failed By Asking the Wrong Marketing Question.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 23 Jan.

- Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/avidan/2012/01/23/kodak-failed-by-asking-the-wrong-marketing-question/

[2] Shih, W. (2016). The real lessons from kodak’s decline. MIT Sloan Management Review, 57(4), 11-13.

Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1802194460?accountid=11311

[3] [flickrfabio]. (2009, April 10). (#1) “How film is made” Kodak 1958 factory documentary (part 1 of 2).

[Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UJ6w1esVcoY

[4] Goldsborough, R. (2013). The changing world of photography. Tech Directions, 72(7), 12-13.

Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1283330858?accountid=11311

[5] BUSINESS: FILM FIGHT: FUJI vs. KODAK: The important issues will be settled by the market, not the

world trade organization / asiaweek. (1996, Jul 01). Asiaweek, Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/228484686?accountid=11311

[6] La Monica, P. “The anti-Kodak: Eastman Chemical.” CNN Money, 27 Jan. 2012. Retrieved from

http://money.cnn.com/2012/01/27/markets/thebuzz/

[7] Hardy, Q. (2015, March 20). At Kodak, Clinging to a Future Beyond Film. The New York Times.

Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/22/business/at-kodak-clinging-to-a-future-beyond-film.html

Very interesting article. Indeed people often think as a company as one fixed entity. But it is a sum of asset both physical, intangible and also people obviously. I tend to believe that when a company’s core business model is jeopardized as dramatically as Kodak was, the most efficient reaction is not reinvention but maybe explosion: spin-offs, employees churn, IP disposals.

There is no reason to regard companies as sacred. They are just a legal structure efficient for organization purposes. The reallocation of people, assets and IP can be part of their life.

Without the disruption at Kodak, HBS students might not have benefited from Professor Shih pedagogic insights and we would not have contributed to some innovation!

Brave post 🙂

I agree with the diagnosis, but not the prognosis.

Yes, whilst the Kodak operating model did have the capability to innovate, it failed to utilise it correctly. As you mentioned, in 1975 Kodak engineer Steve Sasson created the first digital camera. (In fact, until the patent expired in the United States in 2007, the digital camera patent earned billions for Kodak, since other manufactors paid for the rights to use it!) [1] And I agree that the lesson is that when comes to technology, cannablise yourself before someone else does. Take the risk of innovation.

However, in terms of next steps, I do think they are doing the right thing! I would be incredibly interested to hear thoughts on it’s smartphone launch last month:

http://www.kodak.com/consumer/products/ektra/default.htm

Rather than be complacent again and think of themselves as a “a niche chemistry business” in order to survive, they have recognised:

– they have significant brand awareness and power in the camera industry which they can leverage

– smartphone cameras are reducing the need for digital cameras (I got several curious stares during class photo day when I brought mine in…)

As a result, they are taking a risk, and trying to get ahead of Canon, Nikon and Olympus and more! Early reviews are encouraging, but only time will tell whether history is about to repeat itself. [2]

[1] http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/08/12/kodaks-first-digital-moment/

[2] http://www.mobilechoiceuk.com/phone-review/Kodak/Ektra/1154

*on its smartphone

Interesting article. One question I have is how companies can tell when they are going down the path to bankruptcy and how to mitigate that. Should Kodak have done more spin-offs and asset sales prior to bankruptcy to manage value for shareholders? Does it make sense for companies with an old business model to try and pivot into something entirely new, or should they try to manage the decline as best they can and distribute cash to their holders? Would be interesting to hear your take on how Kodak is doing today and whether you think some of their new initiatives will be successful.

Brave post Brian!

I think the Kodak case is quite interesting in that it shows how success can be fleeting in the absence of innovation. The innovation that was missing here was not simply converting to digital, rather looking at how to overhaul a very successful company’s business model. In hindsight, it’s easy to criticize Kodak’s decisions, but I’m not sure I would have done better (perhaps after we do the Kodak case I might!). Imagine telling someone in CocaCola that the future is in ice-cream? It would be a tough sell.