Chemours: How Chemicals are Helping to Cool Climate Change

Chemours has joined the battle against climate change though chemical innovation in response to new global regulations.

The Montreal Protocol – Preventing Ozone Layer Depletion

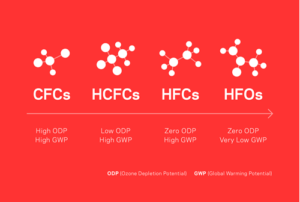

Climate change has long been a focal point on the world’s stage. Dating back to 1987, after the discovery of a large hole in the Earth’s ozone layer, the Montreal Protocol was designed to curb the impact of harmful substances, most notably chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), on the environment. Even though CFCs were widely used in air-conditioning and refrigeration applications, they were found to be harmful contributors to the depletion of the ozone layer, which protects the earth from sun’s ultravioulet rays.1 The protocol helped to eliminate emissions from more than 100 fluorinated gases, and as a result the ozone hole is slowly recovering.2 Some regard it as one of the most successful environmental treaties ever.

In response to the banning of CFCs, chemical companies developed hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) to replace them. While HFCs pose no threat to the ozone layer, they are super greenhouse gas emitters and trap heat in the atmosphere. In fact, even though HFCs represent a small percentage of all greenhouse gasses, they have over 1,000 times the heat trapping power of carbon dioxide, which is a primary cause of global warming.3 Once again, a large problem developed over the years with the continued growth of the coolant and refrigeration markets producing high demand for HFCs and correspondingly a vast increase in resulting emissions.

The Kigali Amendment – Finally Addressing HFCs

On October 15, 2016, more than 170 nations reached an agreement to further address global climate change. The new Kigali amendment has one simple mission: to exclusively target the chemical coolants HFCs. The goal is to cut HFC emissions 85% by 2045 by rolling out a concrete timeline for the production freeze of HFCs in countries around the world.4 If successful, it will lead to the reduction of 70 billion equivalent tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, or two times the annual global carbon pollution. Said differently, the Kigali agreement will prevent an atmospheric temperature increase of nearly one degree Fahrenheit, a significant amount considering it is believed that just a rise of 3.6 degrees will lead to an irreversible impact.3

Chemours is Ahead of the Curve

Surprisingly, the chemical company Chemours was one of the most active supporters of the Kiagali agreement even though it means the migration away from profitable HFC coolants that are the backbone of chemical supply to the fast-growing air conditioning and refrigeration segment.1 In anticipation of such regulation, Chemours has been on the forefront of innovation and set out over a decade ago to find refrigerants that not only didn’t erode the ozone layer but also were not major greenhouse gas emitters.4 Hundreds of millions of dollars were invested towards the development of hydrofluoroolefin (HFO)-based alternatives with low global warming potential (GWP).5 These new refrigerants are very close matches to the HFCs being replaced, providing customers with the solutions they need to meet the changing regulations within the industry at a minimal cost of transition.6

Figure 1: Evolution of Chemical Refrigerants

Helping Combat Climate Change or Fueling Corporate Interest?

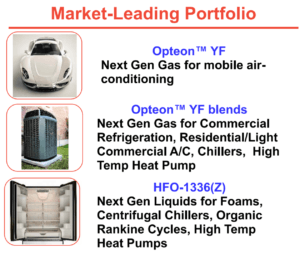

Chemours is well positioned in the fight against climate change. Use of their HFO-based chemicals is predicted to reduce carbon dioxide equivalent emissions from greenhouse gasses by 325 million tons by 2025.5 To provide one example, there are over a billion cars on the road using predominately HFC refrigerants. Chemours can directly target over 100 million cars that are newly produced each year since automakers globally are converting to use HFOs for new vehicle air conditioning systems. Chemours current predictions expect at least 24 million converted vehicles on the road by the end of 2016, with an estimated 50 million vehicles using HFO systems by the end of 2017.5 Ultimately, Chemours has positioned itself well to take advantage of the global climate change crisis. They are not only aiding the continent with environmentally conscious chemicals, but also stand to gain significant financial benefits as the adoption of HFOs increases over time.

Figure 2: Chemours Portfolio of HFOs and their Applications

Accordingly, it is hard not to question whether the motivations of Chemours align with global warming prevention. On an objective basis, Chemours is providing its customers with solutions that meet the changing industry regulations. However, it must be noted that in the past year Chemours announced two major investments (with a magnitude of hundreds of millions of dollars) in large scale manufacturing plants to produce HFO refrigerants – signaling a strategic shift towards HFO production.7 Chemours and similar companies essentially pre-empted global climate change policy by developing HFOs, and then pushed for regulation that serves to grow the market. Taking into account their active role in supporting the Kigali agreement, is corporate financial motivation masking a possible downside of HFOs? Are HFOs the right solution, or will yet another adjustment be needed in the future?

Word Count – 783

Sources:

- Tabuchi, Hiroko, and Danny Hakim. “How the Chemical Industry Joined the Fight Against Climate Change.”The New York Times. 16 Oct. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/17/business/how-the-chemical-industry-joined-the-fight-against-climate-change.html, accessed November 2016.

- McGrath, Matt. “Climate Change: ‘Monumental’ Deal to Cut HFCs, Fastest Growing Greenhouse Gases.”BBC News. 15 Oct. 2016. http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-37665529, accessed November 2016.

- Davenport, Coral. “Nations, Fighting Powerful Refrigerant That Warms Planet, Reach Landmark Deal.”The New York Times. 15 Oct. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/15/world/africa/kigali-deal-hfc-air-conditioners.html, accessed November 2016.

- Williams, Keith. ” Honeywell And Chemours Seize Climate Change Deal Opportunity.”Seeking Alpha. 24 Oct. 2016. http://seekingalpha.com/article/4014208-honeywell-chemours-seize-climate-change-deal-opportunity, accessed November 2016.

- “Chemours Congratulates the Parties to the Montreal Protocol for HFC Amendment Agreement.”Chemours Investor News. 17 Oct. 2016. https://investors.chemours.com/investor-relations/investor-news/press-release-details/2016/Chemours-Congratulates-the-Parties-to-the-Montreal-Protocol-for-HFC-Amendment-Agreement/default.aspx, accessed November 2016.

- Rajecki, Ron. “Post-HFC-phaseout Refrigerant Options.”ACHRNews. 3 Aug. 2015. http://www.achrnews.com/articles/130217-post-hfc-phaseout-refrigerant-options, accessed November 2016.

- “Chemours Expects Opteon™ Portfolio to Reduce Greenhouse Gas by 325 Million Tons by 2025.” Chemours Investor News. 22 Sept. 2016. https://investors.chemours.com/investor-relations/investor-news/press-release-details/2016/Chemours-Expects-Opteon-Portfolio-to-Reduce-Greenhouse-Gas-by-325-Million-Tons-by-2025/default.aspx, accessed November 2016.

I agree with you that several corporate entities anticipated the new regulation and proactively developed environmentally friendly alternatives to HFCs. However, there is no evidence that Chemours and other chemical manufacturers such as Dupont and Honeywell are masking a significant downside to HFOs. It would be important for these manufacturers to conduct studies ensuring that HFOs are safe and effective. The research shows that HFOs have a global warming potential of less than one as compared to 1,300 for HFCs. HFOs are better for the environment than HFCs. In addition, other non-HFO chemical alternatives will likely be used (e.g. propane) or developed in response to the new regulations resulting in a hodgepodge of various chemical substitutes that will not only be HFO-based.

http://www.honeywell.com/newsroom/pressreleases/2015/01/honeywell-starts-full-scale-production-of-low-global-warming-propellant-insulating-agent-and-refrigerant

Very interesting and eye-opening article, as although I was privy to the significant risk posed to the environment by HFCs, I actually did not know that an effective replacement existed. It seems that oftentimes large corporations recognize the need to get away from HFCs, given the nature of their toxicity to the planet from increased carbon emissions and heat-trapping characteristics, yet they are not utilizing HFO as the solution. For example, in the case of Coca-Cola, the use of HFCs in its refrigeration equipment is the company’s number one source of carbon emissions. However, as mentioned in the article below, Coca-Cola has instead switched to using carbon dioxide in its coolers as a refrigerant, which leads me to wonder: are HFOs more environmentally friendly refrigerant substitutes than carbon dioxide, and if so, is there a way to increase awareness of its existence so that companies can begin to utilize the most climate-friendly solutions in their refrigeration processes? If a beverage industry mogul as large as Coca-Cola is looking to find cost-effective and efficient HFC replacements, I’m sure the potential market size for eco-friendly cooling substitutes is vast – the question then becomes how to most effectively capture this market to optimize global climate protection.

http://www.coca-colacompany.com/press-center/press-releases/coca-cola-installs-1-millionth-hfc-free-cooler-globally-preventing-525mm-metrics-tons-of-co2

Great article. Having worked at Chemours in their refrigerants division, it was of particular interest to me! HFCs were becoming very commoditized (patents no longer protecting the technology), so that was also a key driver for Chemours in seeking the next innovation. It is interesting to note that the regulatory agencies have been acting slower than how Chemours would like them to. For example, the EPA said they would restrict the use of R-22 (Freon) to a certain amount a few years ago, but then ended up allowing a larger amount of use than originally stated. This led to a slower adoption of HFO-based chemicals for that year, but now demand is growing fast for HFOs.