Brexit – Serious Implications for the UK’s National Health Service

Brexit presents serious implications on the UK's National Health Service (NHS) staffing and medical supply chains. The NHS needs a clear and decisive plan before it's too late.

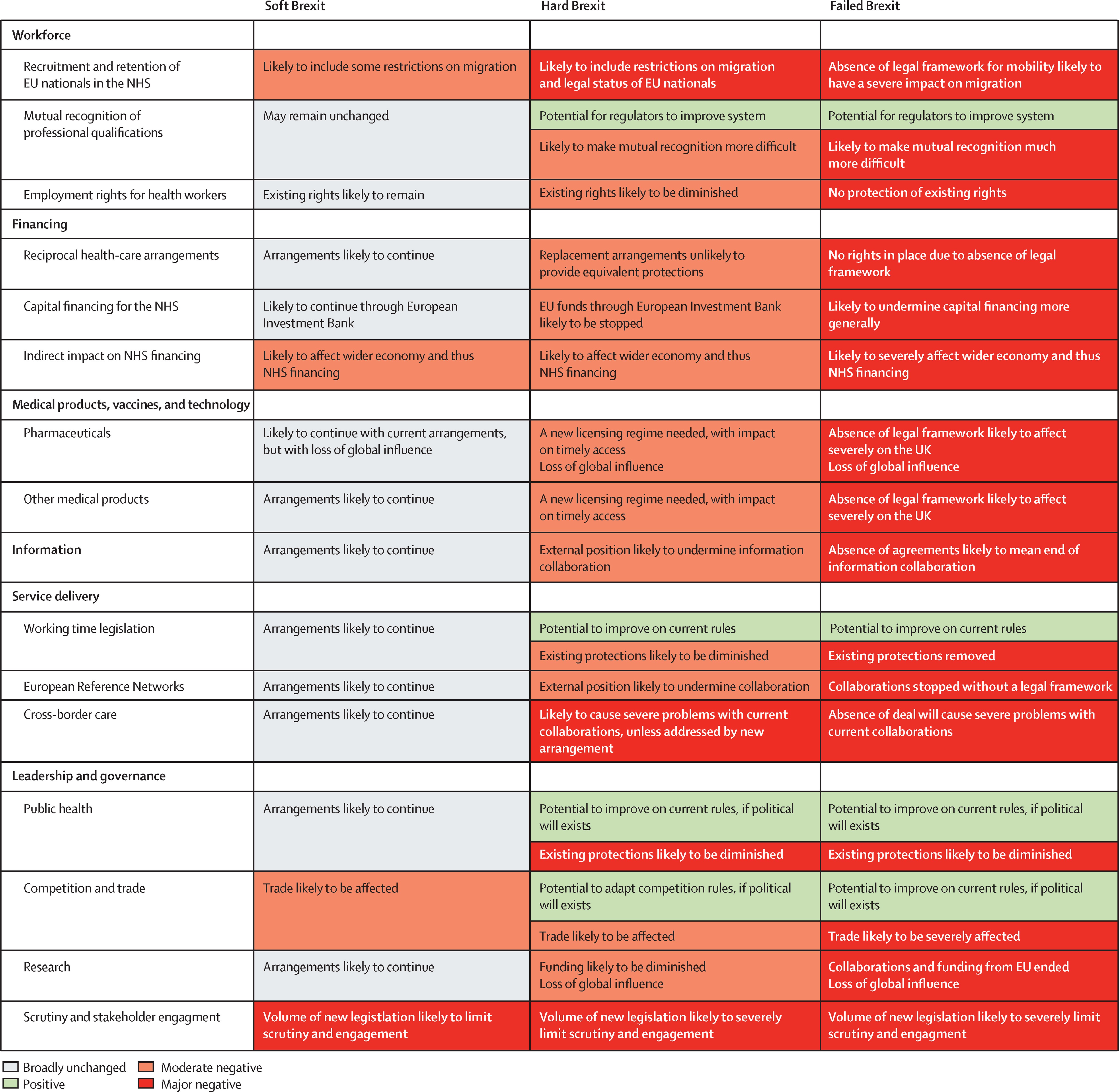

On 23rd June 2016, the UK voted to leave the European Union (EU), a move now widely known as ‘Brexit’. The UK government is currently negotiating a post-Brexit deal with the EU, with both parties trading the ‘four freedoms’ (goods, capital, services, and labor) against each other. Whilst much talk has centered on the implications for businesses, especially those in the manufacturing and service sectors, less attention has been paid to the impact on the UK’s National Health Service (NHS). With more than 1.5 million employees, and an annual budget of over £110B, the institution is the UK’s largest employer1. A recent paper in the Lancet2 has stated that Brexit in any form poses ‘substantial threats’ and that the ‘scale of the task risks overwhelming parliament and the civil service’ (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Probable Consequences of Soft Brexit, Hard Brexit, and Failed (No Deal) Brexit Scenarios2

Brexit has the potential to cause 2 major supply chain issues within the NHS. Firstly, staffing is of key concern; there are an estimated 60,000 EU nationals working for the NHS3, including over 10,000 doctors and 20,000 nurses (5.6% of all NHS personnel4). An uncertain future for EU workers has already caused the number of EU citizens registering as nurses to drop by over 90%5,6. Secondly, the UK’s access to pharmaceuticals and medical supplies from Europe is at risk. Medicines across Europe have integrated supply chains, with thousands of drugs having some part of their manufacturing process in the UK7 . In the event of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, significant delays are expected if World Trade Organization (WTO) rules are implemented.

The key to resolving these uncertainties lies with the quality of the deal that the UK government strikes with the EU. It is clear that the implications of a ‘no deal’ scenario are serious for the NHS. As Simon Stevens, CEO of NHS England recently remarked, the NHS has no contingency plan in place for such an outcome8. The government has stated that some contingency planning is occurring9, however, there is no transparency on this for fear of undermining UK-EU negotiations. Nevertheless, the UK parliament’s Health Committee has stated that it ‘do[es] not believe that this approach will prove sustainable in helping the government to avoid errors and unintended consequences in the process of negotiation.’9

Regarding staffing, the UK’s Health Secretary has said that allowing EU-originating NHS workers to stay in the UK after Brexit is a high priority in UK-EU negotiations, however, there has been no explicit government commitment to this10. According to the National Audit Office, the number of currently vacant NHS clinical posts is over 50,00011; the challenge after Brexit will be to fill these positions whilst immigration is falling.

In the short term, the government needs to explicitly confirm that EU staff working in the NHS will be able to remain in the UK after Brexit. This could take the form of a work permit system that allows free movement of EU-originating NHS personnel within the UK. Over the next 10 years, the number of medical training placements for both doctors and nurses needs to be continually increased. The government must outline and execute a plan for making the NHS self-sufficient in personnel. Part of this will likely involve increasing wages to attract more domestic workers. In the event of a ‘no deal’ scenario, the need for staffing self-sufficiency is more urgent.

The UK needs to remain part of the European medicine market so that new products can be introduced to the UK quickly, and the NHS can rely on supplies from across Europe. The NHS should continue to push for a deal that allows the UK to work closely with the European Medicines Agency (EMA; the EU medicines regulator). Indeed, the EMA is in London – until now, this has pulled pharmaceutical companies towards the UK12. The government has attempted to reassure these companies that the UK and EU will continue to work together on drug regulation after Brexit13. The government should go further, offering attractive incentives for pharmaceutical companies to remain in the UK after Brexit, ensuring that the NHS has easy access to new products in the future.

A couple of key questions remain unanswered as we realize the implications of Brexit for the NHS. How could the NHS reorganize to survive under a ‘no deal’ scenario if EU negotiations are unsuccessful? And perhaps more contentious, what role, if any, should the private sector play in the future of the NHS?

Word Count: 755

[1] “About The National Health Service (NHS) In England – NHS Choices”. 2017. Nhs.Uk. https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/about/Pages/overview.aspx

[2] Fahy, Nick, Tamara Hervey, Scott Greer, Holly Jarman, David Stuckler, Mike Galsworthy, and Martin McKee. 2017. “How Will Brexit Affect Health And Health Services In The UK? Evaluating Three Possible Scenarios.”

[3] Health Committee. Oral evidence: Brexit and health and social care, HC 640 (2016-17). House of Commons, London; 2017

[4] Baker, Carl. 2017. “NHS Staff From Overseas: Statistics”. Researchbriefings.Parliament.Uk. http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7783

[5] Boffey, Daniel. 2017. “Record Numbers Of EU Nurses Quit NHS”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/18/nhs-eu-nurses-quit-record-numbers

[6] “Getting A Brexit Deal That Works For The NHS”. 2017. The Nuffield Trust. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/getting-a-brexit-deal-that-works-for-the-nhs

[7] “Brexit”. 2017. Efpia.Eu. https://www.efpia.eu/news-events/the-efpia-view/blog-articles/brexit/

[8] “Parliamentlive.Tv”. 2017. Parliamentlive.Tv. http://www.parliamentlive.tv/Event/Index/93c0f080-260e-493b-b94f-247920354c8d

[9] Publications.Parliament.Uk. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201617/cmselect/cmhealth/640/640.pdf

[10] Laura Donnelly. 2017. “Jeremy Hunt: Keeping EU Health Workers After Brexit Is A Priority And I’m Sympathetic To Nurses’ Pay Plea”. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/15/hunt-keeping-eu-health-workers-priority-sympathetic-pay-plea/

[11] Nao.Org.Uk. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Managing-the-supply-of-NHS-clinical-staff-in-England.pdf

[12] Majeed, Professor, and Professor Sked. 2017. “Preparing For The Impact Of Brexit On Health In The UK – UK In A Changing Europe”. Ukandeu.Ac.Uk. http://ukandeu.ac.uk/brexits-impact-on-the-uks-health/

[13] “British Ministers Want Post-Brexit Drug Regulation Deal With EU”. 2017. U.S.. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-britain-eu-science/british-ministers-want-post-brexit-drug-regulation-deal-with-eu-idUSKBN19O238

This idea of a “no deal” situation for the NHS under Brexit is a scary one, as you pointed out. It reminds me of similar issues we expect to see in the United States in coming years, often referred to as the “physician shortage.” The number of the elderly, and therefore the number of those with chronic diseases, is on the rise, and we have not seen similar increases in the number of physicians. More importantly, we have seen a shift away from primary care, where the majority of these patients should be seen. In order to address this issue, the United States has been considering options such as utilizing other medical professionals to the top of their license, incorporating more technology, and setting broad standards to which physicians and others must adhere.[1]

I feel as thought the solutions to a “no deal” situation will have to be similar. If we rule out options such as opening private medical schools or expanding the number of physicians in training under the current UK model, then without a healthy influx of immigrant physicians there must be other resources to tap into. One such resource is standardization, something that the UK already does well through NICE and the NHS. Technology can also aid in standardization through EMRs, and also allow physicians to see more patients than ever before through telemedicine and more efficiently with dictation and natural language processing of patient medical records. Lastly, I believe that using NPs, PAs, and even medical assistants to the very top of their ability to practice will be key, as physicians and nurses alone will not be able to handle the burden that a “no deal” solution may bring. These other providers can help immensely in the primary care setting and in the hospital setting, allowing physicians to perform those procedures or tasks that only they can do, promoting efficiency within the system.

1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24191075

This is very interesting – did not realize the scale of the NHS as well as the dependence on EU labor. The potential for a provider shortage is very concerning – I’m curious if on the policy level the UK has explored using technologies like telemedicine or virtual providers to provide care for patients in case a deal doesn’t come to fruition, given the lack of contingency planning in place.

Sud, I found your article insightful and thought-provoking. Interestingly, the challenges that the NHS faces in light of the impending Brexit are not too dissimilar to those that private corporations are also currently grappling with.

In relation to your question around the role of the private sector, I believe that the NHS should attract pharmaceuticals and medical supplies manufacturers to move their production to the UK. In theory, Brexit offers an opportunity to stimulate the local production of medical supplies and pharmaceuticals, enhancing the UK’s industrial base and the broader economy. One way in which the NHS could do so, is by offering long-term contracts to and forging closer partnerships with some of its key suppliers. Given that medicines across Europe already have some part of their manufacturing process in the UK, the NHS and the British government should provide greater incentives to such suppliers. By encouraging them to move their production to the UK, the high tariffs that Brexit would result in, could therefore be avoided.

Sud, very effective way of connecting Brexit / nationalistic actions to a major consideration which is not often done justice in the press. Surely there are a number of very important ramifications on the UK’s public health position. Regarding the public sector’s involvement, perhaps a solution would be to place the power to grant work authorization exceptions in the hands of private placement / staffing agencies. Such a move would help align critical tasks with the core capabilities of the public and private sectors. That is, the government could continue choosing the allocation of healthcare resources while outside organizations would qualify the resources. A public-only approach to this staffing challenge would likely require broad process flow changes in individual hospitals’ HR processes and forego the “buffer” that a centralized company’s staffing pool could provide.

A question I would love to explore further is… the NHS and N.I.C.E. have historically been some of the toughest payors in pharma – will Brexit make them even tougher as they struggle to offset rising costs elsewhere in the system, or will they become softer as dis-integration from the EU makes them a smaller agent / buyer? Also, how will the innovation ecosystem change given the barriers of transit for the PhDs and MDs? Hopefully everything is sorted out smoothly and the UK continues to enjoy an effective healthcare system.

Sud, thank you for bringing up this important issue of how Brexit puts UK’s NHS at risk for staffing and an access to pharmaceuticals and medical supplies. This made me think of the impact of unexpected risks in politics, as the effect on the supply chain goes beyond and it puts the whole country at risk for citizens to maintain healthy lives.

To your question about how the NHS could reorganize to survive under a “no deal” scenario if EU negotiations are unsuccessful, there are several action items the government and hospitals can play. They should increase the pay to professionals to retain them, provide better working benefits and environment for them, and start investing in in-country medical/nursing schools. This is hard to achieve without the authority of the government, thus it is critical that the government recognizes this risk that the NHS faces.

Also on how the private sector play in the future of the NHS, I think that private sector, especially the pharmaceuticals and medical suppliers in UK should take this opportunity to build closer relationships with the hospitals, work on efficiency, price, and quality to compete with those of European suppliers, and market them well to penetrate the market. This way, in a longer-term, UK’s NHS will be more sustainable and at less risk of politics due to the supply provided within the country. Another thought is that this is an opportunity to further invest in technology that can reduce human depend jobs. For example, analysis of data to forecast demand and supply in the pharmaceuticals and medical supplies can adopt the AI and Machine Learning technology, and this will help hospitals to operate with less emphasis on direct labor. Advanced technology will help supplement the lack of talents potentially risked by the failure of the negotiation. And the success depends on the speed of the private sectors to recognize the need and scale the practice.

Sud, excellent job summarizing the key challenges that lie ahead for the NHS, given Brexit.

In terms of the NHS being reorganized, under a ‘no deal’ scenario, the most likely option is the NHS has to raise salaries to attract more domestic headcount or create lower-skilled roles that involve more triage at the top from doctors with more specifically-directed training at the bottom. The NHS has the highest level of healthcare quality in the world [1]. While the Brexit impact would be severe, I think the NHS with some process re-engineering around care, especially primary care, would be able to still maintain higher quality outcomes compared to the rest of the world.

In regards to private options, I believe the private sector does not have a role to play. One of the things that makes NHS work is the idea that central planning and organization creates cost control and price pressure to keep the cost of healthcare manageable. While the funding of the NHS will probably need to be increased, thus breaking the initial Brexit “promise” of saving the British citizens hundreds of millions of pounds on the NHS [2], the private sector will probably increase costs further. Rather, this is simply a problem of hiring and training the appropriate level of personnel, which can be solved without a private market intervention.

References:

[1] Campbell, D. (2017). NHS holds on to top spot in healthcare survey. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/jul/14/nhs-holds-on-to-top-spot-in-healthcare-survey [Accessed 1 Dec. 2017].

[2] Merrick, R. (2017). Brexit director who created £350m NHS claim admits leaving EU could be ‘an error’. [online] The Independent. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-latest-news-vote-leave-director-dominic-cummings-leave-eu-error-nhs-350-million-lie-bus-a7822386.html [Accessed 1 Dec. 2017].

Sud,

I greatly enjoyed reading your post which delved into the impact that Brexit will have on the United Kingdom’s United Health Services. I was particularly interested in the human capital element of your post.

I agree with the short-term solution that you posted in terms of the need for government to explicitly confirm that EU staff working in NHS will be able to remain in the UK after Brexit. As it relates to many governments around the world, there is so much uncertainty and I think the greater measures that government can do to be more transparent will have huge implications. Doing so would limit the disruption to operations that has ensured following Brexit and the wake of uncertainty that it has left.

Thank you for the interesting read and I hope that we have a chance to discuss this further.

Best,

Triston