Brexit and the future of the all-electric Mini Cooper

Uncertainty introduced by Brexit is killing the UK auto industry. Can carmakers do anything to mitigate it? In doing so – how far can they go? Do they have the mandate to attempt coercing governments?

“I was the future once”[1].

David Cameron’s last words as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, 2016

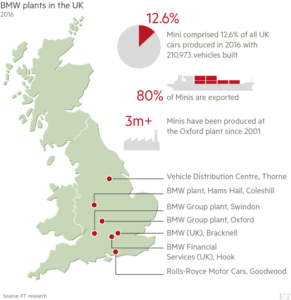

Will the same event that ousted Mr Cameron, the “Brexit” vote, also put an end to another chiefly British dream for the future – an all-electric Mini produced in the UK? The answer will lie with BMW, a German car maker and owner of the Mini brand and its decisions around the design of their supply chain. What are the most important dynamics at this critical juncture?

Why is Brexit of concern to BMW?

Car production features some of the world’s longest and most complex supply chain networks spanning multiple countries or even geographies. If no agreement is reached in the UK-EU negotiations, the tariff system would default to the WTO-stipulated tariffs of 10% on vehicles and 4.5% on parts, which given the average margins of 5-10% in the European car industry [2] could be business-model-changing.

There is some hope in savings on labour with the Sterling down ~15% since Brexit, but firstly, it is a gamble as future rates are by no means guaranteed, and secondly, it will still not make the customs controls go away, which may cause major supply chain hiccups. For factories that only hold inventory for half a day worth of production, the unpredictability of the goods flow introduced by customs processes will require them to keep more stock. This will be costly.

What is the management doing to address the issues caused by Brexit?

Short term

In the short term, BMW does two things – neither of them productive or desirable in the long term.

Firstly, it is waiting. Although it announced it had selected to produce the all-electric Mini in the UK, it was only after warning earlier that it is considering making the car on the continent.[3] Similar statements of support came from other players, such as Honda and Ford, but feet-dragging in actual following through with these vows is evident in the data – investment in the sector fell by 75%[4] over the last two years.

Waiting for uncertainties to be resolved may well be the only option left for BMW, but it is nevertheless painful as other manufacturers unhindered by the Brexit difficulties, such as Tesla or Mercedes, steam ahead gearing their supply chains towards the electric vehicle era.

Secondly, BMW joins other carmakers in petitioning the UK government to provide “urgent clarity” on EU trading relationship. However, it is difficult to see how upping the stakes for the government already desperate to deliver good news from the negotiation table could be productive beyond winning some short term concessions.

Medium term

In the medium term, the company is re-evaluating its supply chain design to brace for potential fallout.

Firstly, there is a clear trend of localizing the supply chain. A recent report by the Automotive Council UK found that the UK factories source 44% of its parts locally, up from 41% in 2015[5]. Even though there are no specific reports that BMW also follows this trend, it can be reasonably expected that it does. Moreover, the German carmaker makes sure that the truly strategic core production processes are sheltered by confining them to the plants and contres of competency in Dingolfing and Landshut[6] in Germany[7].

What else should the management do?

Short term

In the short term, the management should develop contingency plans for the potential need to relocate the bulk of the production. Firstly, it can draw up a blueprint of what a factory relocation would look like from process perspective and make it as cost-efficient as possible before it becomes urgent, e.g. by making sure that the terms of employment of the engineering staff that will enable a smooth technology transfer. Secondly, it can also start scouting for alternative locations to sense the magnitude of concessions they would be able to achieve elsewhere.

Medium term

In the medium term, the company should take steps to build more flexibility into the production process. Firstly, it should try to develop its factories in as more “portable”, i.e. easy to transfer if needed, similar to how GE is thinking about their plants.[8] Secondly, BMW should consider outsourcing more of the simpler processes it currently does in-house in order to transfer the risk to companies that may be better-suited to deal with it (e.g. more diversified between the UK import/export businesses).

Open questions

But the line the companies need to tread when dealing with governments is admittedly fine, which begs two further questions:

- in considering the decision to relocate the plant, does it matter that BMW is a German and not a UK car maker? Would it matter if the majority of its shares were held by German and not UK nationals?

- German business associations are known to accept rule of “primacy of politics”[9]. Is this the right stance in face of isolationist trade policies?

—————

[765 words]

[1] PMQ with David Cameron, 13 Jul 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/av/uk-politics-36781565/david-cameron-i-was-the-future-once

[2] Brexodus? Britain’s car industry gets a Mini boost but faces major problems, The Economist (2017) https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21725584-bmw-announces-welcome-investment-road-ahead-looks-bumpy-britains-car-industry-gets

[3] BMW chooses UK to make fully electric Mini, Financial Times (2017) https://www.ft.com/content/25e37614-7130-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

[4] UK car executives call for ‘urgent clarity’ on EU trading relationship, Financial Times (2017) https://www.ft.com/content/04621320-04fe-33e6-85d8-68e61498d091

[5] Growing the Automotive Supply Chain: Local Vehicle Content Analysis, Automotive Council UK (2017) https://www.automotivecouncil.co.uk/2017/06/new-report-growing-the-automotive-supply-chain-local-vehicle-content-analysis-2/

[6] BMW chooses UK to make fully electric Mini, Financial Times (2017) https://www.ft.com/content/25e37614-7130-11e7-93ff-99f383b09ff9

[7] 2016 BMW Annual Report, https://www.bmwgroup.com/content/dam/bmw-group-websites/bmwgroup_com/ir/downloads/en/2017/GB/13044_BMW_GB16_en_Finanzbericht.pdf

[8] Globalization In Retreat | GE, the Ultimate Global Player, is Turning Local, Wall Street Journal (2017)

[9] The quest for Brexit allies, German business lobbyists will not stop tariffs against Britain, The Economist (2017), https://www.economist.com/news/europe/21708720-unfortunately-brexiteers-bmw-cannot-tell-angela-merkel-what-do-german-business-lobbyists

An insightful, informative and important read. The subject matter is extremely engaging, addressing an interesting dynamics within a traditional UK auto-brand, owned by a German manufacturer, which has a global and diversified operation. As you rightly highlight, the supply chain of car manufacturing is complex, spread out across continents and connected by intricate web of delivery operations. I was surprised to read about the trend of increased local supply of parts in the car industry (up to 44% in the UK), while I believe that the raw materials of these parts would be mostly imported (even at raw steel level, I understand Port Talbot is the only remaining blast furnace that is operating 0in the UK). I believe that the contents of the 2017 budget released by the Treasury this week may serve as an addition to the discussion. Interestingly, there was a clear mention of the electric vehicle (as one of 25 key topics), which I believe is addressing the Mini-production: “An extra £100 million will go towards helping people buy battery electric cars. The government will also make sure all new homes are built with the right cables for electric car charge points.” On the other hand, the devil is in the detail, and the government has (subtly) inserted an extremely grim forecast of declining revenue (table 1.2 – staggering GBP 20.6 billion downward forecast of revenue by 2021!). While BMW may be ‘waiting’, has the government already moved on to a state of no-deal with EU and retreat to WTO tariffs? Troubling signs to any UK based manufacturer. (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/autumn-budget-2017-documents/autumn-budget-2017#annex-a-financing)

Great article.

To respond to your questions – I believe BMW has an obligation to its shareholders to produce the Mini in the most profit maximizing manner. With the present day uncertainty around Brexit, BMW is right to be hedging their bets and delaying investment. However, I believe they should take more immediate steps to abandon the Brexit opportunity (especially in light of the news Motoaki references above). By going ahead and moving the production facility elsewhere, BMW can beat their competition to finding the largest concessions/etc.

Interesting and very topical read. I think if I were in BMW’s shoes I would very decisively look to relocate my operations to Germany (or another EU country). I do not think that there would be a significant benefit to producing locally in UK. According to AECA, the UK had 2.7 million vehicle sales in 2016 vs. 14.7 for the broader EU. From the lens of maximizing addressable market and minimizing business risk that makes me believe in strongly prioritizing access to EU markets vs. UK. The uncertainty of what post-Brexit UK-EU trade looks like exacerbates that and I think that even if it turns out that BMW would have been able to produce locally in the UK, I would imagine that the lost opportunity would be mitigated by the fact that Germany and the UK are still in relatively close geographic proximity. It’s not like thinking about the cost-benefit of having a plant in China, which would dramatically reduce costs of transporting goods to end markets. To the question you posed at the end, I do think that in practicality BMW would consider this differently if it was a UK company instead of German. I still believe that a sense of duty by corporations to contribute the greater good of their home countries changes perceptions of the “right thing to do” from a moral standpoint.