A Perfect Storm: When Hurricanes Hit the Medicine Supply

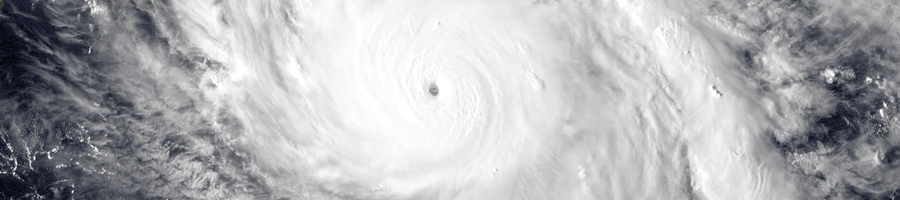

On Sept. 20th, Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico, disrupting a major pharmaceutical manufacturing base. If the FDA is to prevent future medicine shortages in the face of climate change, it must heed the warning.

Hurricane Maria: a pharmaceutical crisis

On September 20th, Hurricane Maria slammed into Puerto Rico. The storm decimated Puerto Rico’s infrastructure, causing billions of dollars in damage and knocking out the power supply for months.[1]

While Maria was singularly devastating in the Caribbean, its ripples extend far beyond the Atlantic. Puerto Rico is home to 25% of the United States’ pharmaceutical exports, due in part to a tax subsidy that ended in 2006.[2][3] Today, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) fears that 30 drugs and 10 biological devices, which are produced primarily or exclusively in Puerto Rico, could see national shortages as the island struggles to restart its economy.[4]

Pharmaceutical manufacturers in Puerto Rico now risk running out of essential supplies, including the generator fuel powering their factories and refrigerators. More critically, they are still struggling to locate employees, who are grappling with catastrophic personal losses from the hurricane.[5]

Could Maria be a sign of even worse to come? Climate science gives reason to worry. On the one hand, scientists are uncertain whether climate change will cause the total number of hurricanes to rise or fall. However, warmer oceanwaters and higher sea levels increase the destructive power of hurricanes that do occur. This means storms with greater rainfall, larger sea surges, longer lifespans, and higher likelihood of making landfall.[6] The supply of essential medicines could increasingly be at risk.

The FDA responds

Fearing immediate shortages of critical medical supplies, the FDA is racing to stem the bleeding. It has launched a task force to oversee storm-related supply gaps and deployed teams to monitor each of the 40 at-risk products.[7][8] The agency is coordinating with companies and government authorities to facilitate distribution of fuel, medical-grade gases, and other critical supplies. It is also playing a coordination and advisory role to address logistical and transport challenges facing the affected companies.

In the medium term, the FDA is working with federal and local governments to ensure that critical plants, which are the primary producers of at-risk medical products, are prioritized as Puerto Rico rebuilds its power grid.[9] The FDA is also providing companies expertise as they plan for similar critical risks in the future.[10]

Planning for the risks

Moving forward, the FDA should revamp its contingency plans to account for the growing hazard of extreme weather events. The dangers include not only fiercer hurricanes but also more severe droughts, flooding, and rainfall, which could impact producers up and down the supply chain.

The FDA should start by conducting a thorough climate-risk analysis across the value chain. Where else are operations concentrated in geographies vulnerable to climate change? This analysis should span not only the production of final goods but also the supply and warehousing of intermediate components.

For products manufactured in high-risk geographies, the FDA can bolster resilience by enhancing emergency readiness, raising inventory stockpiles, and promoting geographic diversification.

- Emergency readiness: The FDA should work with firms to ensure that critical factories meet higher standards for infrastructural soundness, emergency supply stockpiles, and response plans. Superior planning to provide employees immediate emergency support, for example, might have helped firms recover more quickly from Hurricane Maria.

- Inventory stockpiles: The FDA can encourage firms, hospitals, and government agencies to expand stockpiles of the medical supplies most vulnerable to extreme weather events. While inventory imposes space, refrigeration, and wastage costs, larger stockpiles will increasingly be justified as climate risks grow.

- Geographic diversification: Over the long-term, the FDA can encourage firms and government agencies to avoid clustering critical production in vulnerable geographies. Federal tax policies led to the pharmaceutical buildup in Puerto Rico; regulatory and tax policies can similarly facilitate geographic diversification of the supply chain in the future. This strategy, however, should be pursued with care. While diversification of critical supplies is important, the U.S. government also has an interest in sustaining Puerto Rico’s pharmaceutical industry, which powers 30% of the island’s GDP.[11]

Moving forward, the FDA will have to answer some difficult questions. Given uncertainty around the impacts of climate change, how much more should the pharmaceutical industry invest in emergency readiness? To what extent should the FDA advocate for reinvestment in Puerto Rico’s existing infrastructure versus moving production elsewhere? The agency’s leadership will need to answer these questions carefully – and quickly. It’s only a matter of time before the next wave hits.

(717 words)

[1] Brian Resnick and Eliza Barclay, “The Danger in Puerto Rico’s Widespread Power Outages,” Vox.com, October 16, 2017, https://volume.vox-cdn.com/embed/b15d69e1b.

[2] Nathan Bomey, “Hurricane Maria Halts Crucial Drug Manufacturing in Puerto Rico, May Spur Shortages,” USA TODAY, September 22, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/09/22/hurricane-maria-pharmaceutical-industry-puerto-rico/692752001/.

[3] Aaron Schrank, “What Will Be Hurricane Maria’s Impact on Puerto Rico’s Drug Industry?,” Marketplace, September 25, 2017, http://www.marketplace.org/2017/09/25/economy/weather-economy/puerto-rico-manufactures-quarter-all-us-exported-drugs-what-will.

[4] “FDA Updates Drug Manufacturing Situation in Puerto Rico,” DCAT Value Chain Insights, November 7, 2017, https://www.dcatvci.org/pharma-news/4772-fda-issues-statement-on-role-of-medical-product-manufacturing-in-puerto-rico.

[5] Bomey, “Hurricane Maria Halts Crucial Drug Manufacturing in Puerto Rico, May Spur Shortages.”

[6] “What Is the Link between Hurricanes and Global Warming?,” Skeptical Science, accessed November 16, 2017, https://www.skepticalscience.com/hurricanes-global-warming.htm.

[7] “FDA Updates Drug Manufacturing Situation in Puerto Rico.”

[8] Kirsten Korosec, “FDA: Puerto Rico Faces ‘Critical’ Drug Shortages After Hurricane Maria Devastation,” Fortune, September 26, 2017, http://fortune.com/2017/09/26/puerto-rico-drug-shortages-fda/.

[9] “FDA Updates Drug Manufacturing Situation in Puerto Rico.”

[10] Korosec, “FDA.”

[11] “FDA Updates Drug Manufacturing Situation in Puerto Rico.”

Your title – A Perfect Storm – could not be more fitting to the issue at hand – that is, not just the storms themselves, but the supply chain disasters that follow these increasingly common natural disasters. While your recommendations on emergency readiness and inventory stockpiling are (at the very least) absolutely necessary, I do worry (above all else) about gaps in infrastructure that might prevent them from even making a dent in relief efforts in the first place.

As I understand it, stockpiles aside, the biggest issue in Puerto Rico was the lack of infrastructure on the island, and the complete inability to navigate through the ravaged region. Even if we HAD major stockpiles hidden in Puerto Rico, there would’ve been no way to reach them. And so, while we MUST prioritize the development of such stockpiles (at whatever cost), we must also inevitably reinvest in the infrastructure of Puerto Rico – not only for the good of the state, but for the good of the pharmaceutical industry as a whole.

That said, if the only reason we stockpiled pharmaceutical goods in Puerto Rico in the first place was the tax subsidy that ended in 2006 (as you’ve referenced above), it seems to me that this would be a good time to refocus our pharma-related investments elsewhere, and stockpile goods in a place both cheap to hold inventory, and perhaps less susceptible to climate-related disasters.

This goes without saying that as a country (of which Puerto Rico is a part), we must rebuild the roads, the businesses, the infrastructure as a whole of Puerto Rico – but this won’t (and shouldn’t) be the job of the FDA, but rather the federal government at large.

Yikes.

It seems that Puerto Rico ended up being the home to 25% of US pharmaceutical exports due to federal contribution, i.e. the tax subsidy you mentioned. Therefore, it’s up to those at the federal government level to tighten regulations and impose restrictions on the contributions they offer. Before Puerto Rico receives federal contribution, our federal government should require that Puerto Rico meet stricter standards for infrastructural soundness. As Alison mentions, I don’t think this should be the job of the FDA, which at its core is a regulatory agency. To me, the key question is: how should the federal government account for the impact of climate change so that being emergency-ready does not fall entirely on the shoulders of businesses, organizations and industries across the nation?

Thanks for the interesting take on yet another impact of extreme weather on our society. I had no idea that Puerto Rico was so central to US drug supplies due to an unfortunate distortion in the tax code.

I know that your post focused on the FDA, but I’m curious to what extent the pharmaceutical companies are responsible for maintaining supply in the face of inclement weather and to what extent they’ve been working on this without government involvement. The preponderance of goods in our economy don’t have the same sort of bureaucratic involvement and yet seem to have fairly resilient supply chains. I also wonder if there’s a stopgap/ emergency release valve of sorts here, perhaps in the form of allowing drug imports from other countries if US supply reaches a critical level. Further, I wonder if the example of Maria illustrates the danger of a lean supply chain with minimal levels of inventory. In the event of a serious disruption to global trade due to weather or other reasons, how long would patients in the US have access to medicines before shortages took hold? I’m not sure whether government involvement (whether from the FDA or another side) is the right answer here, but holding ample inventory, while wasteful when viewed through a narrow TOM lens, could be a life-saving policy in the long run.

Thank you for writing about this topic, it is something that wasn’t planned for until a major event like this were to occur.

Previously working in the Pharma industry at Johnson & Johnson, I knew that there were major drug production in Puerto, but I didn’t realize that some of the drugs were produced and approved ONLY in Puerto Rico. I didn’t realize there was this much risk in the system. I wouldn’t be surprised if there was major implications and ripple effects throughout the world and the where ever the drugs are used.

I think your long-term solutions are well thought out and, most importantly, actionable!

Thanks for the insight Daniel – thought provoking piece. Having lived through the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, I can sincerely empathize with the tragic situation Puerto Rico is facing. Given the humanitarian crisis associated with such widespread devastation, the pharmaceutical industry has a delicate balance to strike when approaching solutions to the supply chain management problem, as they need to make their case for assistance without appearing to divert the already limited resources from hospitals and other emergency services. However, as Katie Johnson reported in the New York Times, “returning the drug and device industry to its feet […] is crucial for ensuring the island’s economic recovery as well as safeguarding the supply of medicines and devices to the rest of the United States.” [1] It’s a fine line to walk, but a critical one to get right and I believe the pharma companies should take on their fair share of the costs (or even more of their fair share) of restoring the energy grid and water supply (instead of waiting for government assistance).

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/04/health/puerto-rico-hurricane-maria-pharmaceutical-manufacturers.html

I’m with Sam here in wondering whether the solution to this problem is best driven “top down” (i.e. by the government) or “bottoms up” (i.e. by pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and other private actors). The key question in my mind is whether private actors bear the full cost of stockouts. Most likely, the answer is no: when a stockout causes death (due to unavailability of key drugs), the social cost is much greater than whatever hospitals charge pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors.

I wonder: would forcing private actors to bear the full cost of stockouts (for instance, by forcing them to purchase life insurance for patients or paying a fee to the government when patients die due to unavailability of key drugs) compel private actors to build a more resilient supply chain on their own, or will government need to take a more prescriptive, top-down approach, as Daniel suggests (such as mandating stockpiles, conducting studies, and encouraging geographical diversification)? Would imposing such fees lead to more efficiency in the supply chain, or would the threat of fees cause excessive risk aversion (similar to the threat of malpractice suits)?

Daniel, thank you for bringing this issue to light. I think your suggestions for high climate risk environments are excellent and implementable. I wonder if these drug companies considered the potential of disaster related costs, such as the ones they are experiencing now, when they were considering the benefits of the tax breaks offered by Puerto Rico. In finance, we have learned that we can do a lot of analysis that examines risk as part of the equation. We haven’t talked about models of assessing risk in TOM and I wonder if there are standard practices for doing so in Operations Management– as your post illustrates, this would be a valuable exercise.

My mother was born and raised in Puerto Rico and the rest of her family still resides there. My grandfather was and economist and was heavily involved in the industrialization of Puerto Rico (though not with pharma). I wish I could have a conversation with him about this very issue. As with all countries, some industries are better suited for the island than others. We have talked about the pluses and minuses of moving manufacturing from one country to another and in this instance it makes me sad to say that that Puerto Rico’s climate risk, infrastructure, and distribution network do not seem to make up a favorable environment for pharma. I would urge industries to carefully evaluate and try to quantify the seemingly intangible costs of doing business in a place that is using a subsidy to draw an industry– if it wasn’t a great manufacturing/ market fit without the subsidy, don’t assume that tax breaks will pay off in the long run.

It is surprising that there some drugs that are exclusively produced in Puerto Rico! Thank you for bringing up this topic

From the actions you propose the geographic diversification is the one that makes more sense to me. I believe that the emergency readiness and the inventory stockpiles will help to REDUCE/MITIGATE the risks you mention. However, reduction or mitigation is not enough when we are speaking about health issues.

I believe that geographic diversification ELIMANATES the risks of running out of drugs. This is probably the most expensive option, but mainly because of taxes reasons. In this sense, they could try to lobby the government to reduce taxes.

Hi Daniel, Thanks for bringing this issue to light! However, I wonder if the FDA is the right body to be held responsible for this issue – it feels to me more like a central/state ministry/government issue.

I also struggle with the question of who should be paying for this – taxation is designed by the government with the explicit purpose of influencing market behavior. To hold the companies accountable for doing exactly what the tax structure required of them, acting in shareholder interests and optimizing their profits and not creating buffers for what is obviously an unforeseen event does not seem fair. This is a failure of public planning and I believe, requires another tax structure overhaul to incentivize the drug manufacturers to drive the behaviors you have mentioned in your recommendations. In the current economic environment, a macro lens needs to be taken and the right balance needs to be set between keeping companies competitive, safeguarding PR’s economy and between preparing for these climatic events.