WeChat: The End-All Platform?

WeChat…WeBuy, WeBook, WeEat, WeBank, WeDate? A glimpse into life in the People's Republic of WeChat

In the world of mobile, WeChat represents perhaps the textbook example of a platform business. What started as a mobile messaging app has quickly evolved into what some in the industry have dubbed “a portal, a platform and even a mobile operating system.” Its 846 million users can buy movie tickets, hail cabs, order food, send money to friends, play games, book doctor appointments, pay utility bills, read up on news, check in for flights, meet local strangers, donate to charities – oh, and of course, chat with other users around the world via text, voice messages, free Skype-like voice calls or video calls. So what can we learn from WeChat’s growth and is it truly poised to take over the world, or at least China? (Hint: A lot, and maybe)

Bootstrapping early growth

WeChat was initially launched in 2010 as a mobile instant messenger service by the Chinese internet giant Tencent, which was smart for choosing to build a mobile-first messenger platform rather than attempt to adapt its existing desktop-first IM service, QQ, to mobile phones. WeChat’s status as an offshoot of a parent company with deep pockets was critical to its early growth trajectory. Tencent employed a number of growth hacks to bootstrap WeChat’s initial user growth: most notably, it tapped into its then-700 million QQ user base to convert them into WeChat users – in the first few months of operations, a QQ account was the only way to sign up for a WeChat account. This allowed the app to gain early traction, independent of its design and functionality.

WeChat also made the user action of adding other users a seamless process by giving each user a unique QR code and building in a native QR scanner – something that social communication services such as Snap have adopted.

Scaling up (and monetizing at the same time)

Once WeChat reached critical mass, it turned to the question of long-term growth. The strategic decision it made has been pivotal in allowing the company to gain the ubiquitous standing it has today among Chinese mobile users. Given messaging’s strong network effects within a local market but relatively weaker network effects globally between markets, WeChat chose to initially remain focused on the Asia market, particularly China, but to become a horizontal aggregator of services across many verticals – financial services, gaming, transportation, delivery, appointment scheduling, online dating and so on. This has allowed WeChat to shift from simply being a messaging service into becoming a one-stop platform for multiple products and services – an entire ecosystem that lives on top of WeChat. This, in turn, has allowed WeChat to capture value at each transaction point via commissions and advertising. Today, WeChat’s ARPU is estimated to be more than $7, compared to, for example, around $2.50 for Snap.

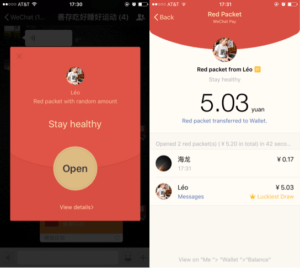

Much of this has been enabled by what is perhaps the single smartest move on its part – to convince its massive user base to link their payment credentials to their accounts, which greatly reduces the friction of subsequently using WeChat as a digital wallet for engaging in various other transactions. WeChat Wallet is essentially the Trojan horse that “unlock[s] new monetization opportunities for the entire ecosystem,” as Connie Chan at Andreessen Horowitz observes. The way it was able to successfully accomplish this is in and of itself a clever growth hack to the universal chicken-and-egg problem of getting both merchants and users to adopt WeChat Wallet.

As Chan describes, WeChat leveraged the Chinese cultural phenomenon of “red envelopes” – small, physical red envelopes that contain cash and are given out as gifts to family and friends during holidays or special occasions – and launched a peer-to-peer feature called Lucky Money (renamed Red Packets) just before Chinese New Year in 2014 that allowed users who linked their payments info to virtually send real money to other users. Flash forward to last year: more than 420 million WeChat users sent 32 billion red envelopes in the span of the six-day Chinese New Year, with 409k digital envelopes sent per second at the peak. Compare this to Paypal’s 4.9 billion transactions globally in all of 2015, and the implications are remarkable.

Beyond payments, WeChat has built out a web of millions of “apps within an app,” turning WeChat into a browser of sorts for mobile websites. These “lightweight” apps within WeChat, known as “official accounts,” allow various businesses, celebrities and others to use APIs within WeChat for services such as payments and geolocation. Users simply add these accounts in the same way they would add a friend, and can then interact and transact with them. In addition to facilitating usage of WeChat, this feature has spurred a whole new trend among Chinese app developers, who can now choose to launch their apps entirely on WeChat (or as a version one test of their app) and tap into the enormous WeChat user base, rather than launch a standalone app.

Future growth opportunities & challenges

No path to world domination isn’t littered with a fair share of challenges, of course. For WeChat, those are likely to be continued user and monetization growth, and competition. As WeChat starts to hit the ceiling in terms of user acquisition in China, it has turned to geographic expansion. Tencent made a push for WeChat abroad in 2013, with superstar endorsements (e.g., Lionel Messi) partnerships with local businesses (e.g., Food Panda, Lazada and Easy Taxi in Southeast Asia), heavy marketing spend and other strategies. Yet the service did not catch on significantly beyond Southeast Asia, reaching at its peak 100 million users outside of China, and Tencent announced in 2015 that it would pull back on its efforts to promote WeChat internationally. This means that WeChat has opted to use its dollars build out its platform further in order to unlock new monetization opportunities within China, rather than take the path that companies like WhatsApp and Snap have done in going abroad.

Finally, despite its dominant status within messengering in China, WeChat grapples with competition – less from players in its direct space, but more from the exact partners that drive its powerful platform. A delicate balance exists for WeChat between supporting new businesses to build their presence on WeChat and incentivizing those businesses to remain on WeChat rather than go off on their own without WeChat integration.

None of those threats appear to be imminent, though. For now, life is good in the People’s Republic of WeChat.

Very well written post Kathy. Wechat certainly has become a one stop shop for most needs. I didn’t realise untill I read this post that they had diversified into so many areas through a single application. Not just that, they have carved a well monetized plan while scaling up.

Nice post Kathy. A few months ago Wechat went beyond “official account” and launched a Mini Program initiative, which essentially is building an app store on this platform and, arguably, an operation system. My post is actually about its new initiative: https://d3.harvard.edu/platform-digit/submission/wechat-mini-program-one-step-further-evolving-into-a-one-stop-solution-platform-from-a-messaging-product/?notice=success¬ice_message=Your%20submission%20has%20been%20published%20successfully.

What I found interesting is the question you raised about Wechat’s oversea expansion. I kept thinking why in the states the messaging and social media markets are so fragmented, why there is no such a player like Wechat being a one-stop shop, and why it is difficult for Wechat to take off in Southeast Asia market. Your thoughts are welcome:)

In my IFC China course this past January, a visiting professor went to buy us noodles from a street vendor in Shenzhen while I grabbed a table at the local coffee shop. Sporting a giant wok, noodles, a wooden spoon, a propane canister and a moped the street vendor did not accept cash, but only WeChat payment functionality. Very intriguingly, the street vendor’s target customer was everyone from blue-collar early morning construction workers to late-night party goers. WeChat united and made life easier for them all.

Wow- very interesting post, Kathy! Certainly, I have heard of WeChat, but I never knew of all its capabilities and functionalities. I wonder what WeChat’s relationship to the Chinese government is like. I would presume Tencent’s history and relationship with the Chinese government has helped fuel its success.

Also, I would definitely agree that WeChat’s “secret sauce” stems from its low-friction value capture model. The other day, I was purchasing an item on Amazon and remember thinking how the quick check-out process not only saved me time but also reduced the likelihood of me overthinking the purchase of an item. Consequently, I find myself much happier than before. In another instance, I found myself increasing my purchase of apps on Apple’s app store because of how quick and easy the process is to do so — you just verify your finger print!

I wonder what WeChat’s long-term strategy is. It seems that the company might be primed to have its own app store. If it does this, what’s to stop WeChat from going into hardware and developing its own smartphone?