Tinder: The dark side of network effects

With the proliferation of the internet and smartphones, we live in a world of unlimited options, including those related to romantic possibilities. Due to network effects, there is a new source of value creation and capture in the dating world. But are network effects always positive?

Tinder: When users sign in to this app, a seemingly unlimited list of other nearby users is immediately presented. Users quickly swipe through photos to determine potential romantic interests. This app is built on the premise of having a large installed user base. The more users on the platform, means the more choices that users have, and in turn, a higher-quality app experience, and a greater chance of finding the perfect match. As of April 2015, there were 1.6 billion Tinder profiles and 26 million daily matches. This is an example of direct network effects at play through a positive feedback loop.

Value Creation: Tinder provided a free, easy way for users to meet potential matches. It’s large database is the greatest source of value creation. While it would not be difficult for a new challenger to recreate the features available on Tinder, the install base presents a higher barrier to entry. However, it is important to note that multi-homing is quite common for users of dating apps, and this does not limit the value created by the individual app.

Value Capture: Tinder initially did not capture value. The service was free and unlike many dating websites, the app did not include ads. However, the company is now entering a freemium model, in which users can pay a monthly subscription fee to access additional features.

In order to scale up, businesses that exhibit Direct Network Effects, like Tinder, must build critical mass locally, rather than immediately focusing on geographic expansion. This is similar to the Uber model. If I am in Boston, I don’t have an interest in the number of drivers or riders Uber has in New York. Similarly, a Tinder user in Boston is not affected by the size of the Tinder user base in New York. Additionally, in order to reach critical mass locally, companies may rely on users making requests of friends. These dating apps often include a button to invite friends to the platform.

However, I question whether network effects based on an increasingly growing user base always have positive effects. Clearly, the initial user base must reach a critical mass in order for a dating app to be effective. But when a network expands too large, then congestion can occur, with irrelevant results that may lower the quality of the offering. A common criticism of many dating apps is that women get bombarded by a slew of lower quality users.

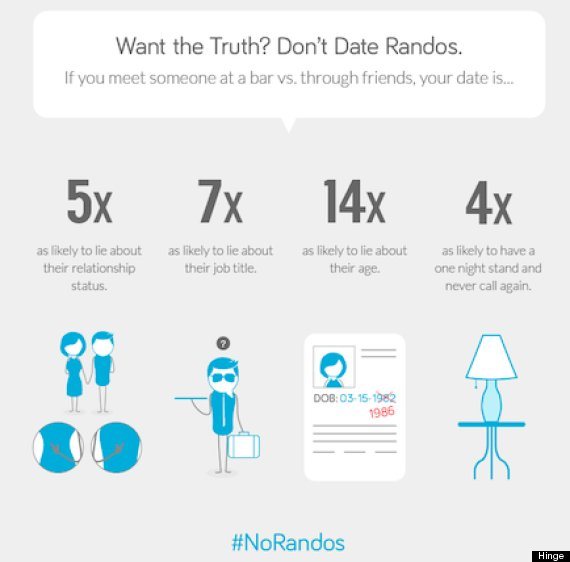

Newer apps, such as Hinge or Coffee Meets Bagel take advantage of network effects, but with smaller installed user bases. These apps only include individuals to whom you already have a connection, friends of your Facebook friends. Coffee Meets Bagel gives each user only one potential match per day. The size of the installed user base is less relevant to the app’s ability to create value. Rather than maximizing the size of the install base, this app is intentionally targeting a certain subset of consumers. 96% of Coffee Meets Bagel users hold at least a Bachelor’s degree. This means users are more likely to find similarities with each other, and the quality of the app is increased. In fact, Hinge recently launched the hashtag, “#NoRandos,” reflecting it’s smaller install base (see Hinge marketing image below).

Additionally, by connecting to a user’s Facebook friends, these apps are taking advantage of indirect network effects. Increases in a user’s number of Facebook friends increases the value users have through Hinge or Coffee Meets Bagel, because there are more possible matches.

Tinder vs. Coffee Meets Bagel reflects the battle of positive vs. negative network effects, and it remains to be seen which business model will ultimately be victorious.

Another type of indirect network that we can discuss is advertising within the app. To my knowledge, Tinder is not taking advantage of paid advertising. Brands are getting creative with guerrilla tactics by setting up profiles while leveraging Tinder’s large user base. Here’s an example:

http://guerrillablog.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Porsche_tinder.jpg

Internally, Tinder can benefit from ads as well. Tinder started off as a hook-up site, but has since expanded into dating. Unclear if they want to break away from the hook-up culture altogether, but they can use ads to change their own image with socially responsible ads such as this campaign against sex trafficking:

http://cdn.psfk.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Tinder-Sex-Trafficking-Immigrant-Council-5.jpg

Thank you for your post, Jennifer. It is certainly interesting to consider that network effects can turn negative beyond a certain point. However, it is worth noting that this phenomenon is unique to platforms where (1) the user relies on the platform to make recommendations, and (2) the platform’s technology struggles to do so in a satisfactory way. For instance, there is no congestion-based downside for WhatsApp because users decide who they want to message with on their own. Moreover, there is no negative network effect for Google from the relentless expansion of the Internet because its algorithm is sufficiently sophisticated to produce the most relevant results for users’ searches. Perhaps, therefore, Tinder’s problem is less structural and more that it purports to offer relevant results without having the necessary data or technical capacity to do so.

I was also intrigued by your analysis of the nature of network effects for dating apps vs. other platforms. You are correct to point out that because dating is primarily a local activity, dating networks are built locally. This is a limitation on the scalability of a dating network. Another limitation is that there is much greater churn in the addressable user base vs. other platforms. A typical person might register for a dating app in college and the average age for marriage is in the late 20s (27 for American women and 29 for American men – http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/14/married-young_n_4227924.html). As a result, the time period over which a dating app is relevant is quite limited for the majority of users (though, of course, there will be a long tail of people who take longer to find their significant others, who never do, or who get divorced and re-enter the pool). Indeed, it is ironic that the more value a dating app creates for its users, the more churn it will have – that is, a dating app that successfully matches two compatible people will take them off the market. This is in stark contrast to a platform like Uber, which can be used for a lifetime and for which a positive user experience is likely to reduce churn. The practical effect of high user churn for dating apps is that it significantly weakens the network effect. Because dating apps are constantly losing large portions of their user base, they must constantly attract new users – they have to run just to stay in place. If the next generation of users perceives them to provide less value, network effects will not be enough to save them.

Very interesting take on what has become a large part of the life of single 20-somethings (and 30-, and 40-somethings, too). This particular network has some other (negative?) externalities: it perfecetly feeds into the predominant love for optionality among our generation (as in, why keep dating this person, if so many potentially better matches await at the tip of my swiping finger?). In many ways, it commoditizes dating, leading to potential temporary asymmetries in customer satisfaction between e.g., genders. This may indeed endanger the very business model: Tinder may become heavily male skewed, while apps such as IvyLeague (accepting only customers with degrees from top schools) are already heavily skewed towards females. If this imbalance increases, you can imagine hoards of dissatisfied customers (this time on both sides) leaving such platforms.

Nice post Jennifer! I like that you distinguish between Tinder and Hinge/CmB but I would disagree in your assesment of how the network effects impact the quality of the platform. I would argue that the differences you see between the services are not a function of the number of users on the platform but rather of the filtering mechanisms employed to match users. Tinder is just local whereas Hinge is social. While it seems you prefer the Hinge model (as do I), I believe that it is more an expression of product strategy rather than product quality. Tinder is meant for quick hookups; Hinge for dating. The difference drives their decision to provide potential matches for you based on different criteria. Tinder could do the exact same thing as hinge, since you login with facebook and give access to friends but chooses not to because that choice would be misaligned with their strategy. Size of user base does not dilute results on hinge because you are given a subset of users as potential matches based on proximity of friendship.

I agree that dating apps have network effects; however, because multi-homing is so high (if we look at people as app developers, and their ability to go onto other sites as their ability to develop on other platforms), it is difficult for apps to differentiate themselves in the marketplace. Furthermore, in spite of having high network effects, it has been incredibly difficult for the Tinder and Hinges of the world to become profitable. Of the 1.6bn Tinder subscribers, only 260k are paying for the service, and Hinge doesn’t even have a premium tier yet. I understand the freemium model, and trying to get users on your platform before you start to charge them – but with so many freemium substitutes coming available everyday (Bumble, Happn, The League, Align, How About We to name a few), I don’t know that these businesses will ever turn a profit.