The Need to Knead: How the “Bread Boom” is Forcing Adaptability

Cooped up in quarantine, people everywhere are turning to bread-baking for comfort and fun. Unprecedented consumer demand for flour and yeast has strained suppliers, resulting in secondary markets and new businesses leveraging digital platforms.

Like many Americans, I may have gotten a little zealous with my apocalyptic preparations and now find myself the proud owner of no less than FOUR jars of peanut butter. Fortunately, I love peanut butter. Unfortunately, I don’t love Wonder bread. Not only is it unsatisfyingly plain and tasteless, but I now have to risk pandemic disease to go to the store to get it. My quarantine routine of pajamas, zoom calls, Netflix binges, yoga, and Mario Kart just isn’t compatible with showering, real pants, Uber, facemasks, and risking COVID19 for Wonder bread. Additionally, many people are finding that bread and other commodity food items just aren’t available at many stores—the shelves are still wiped clean. While “there is plenty of food in America,” the perception of shortages has led to excessive consumption and increases in demand across all grocery categories of over 30%. [1] The more store shelves are empty due to panic buying, the greater the perception of shortages which in turn fuels the cycle of panic shopping. Thus I am faced with a common dilemma—I’m hungry and have a lot of peanut butter but nothing to eat it with.

However, as I reminisce back to my childhood, I vaguely remember my mother using the kitchen oven for something other than frozen pizza—bread! Homemade bread! Eureka. A unique combination of circumstances has led an unprecedented number of Americans to the same conclusion: baking bread is a great idea. First, it takes lots of time. My mom is an expert bread maker and often spends 3 hours or more on each batch. In our modern lives, three-hour stretches have always been hard to come by—until now. Suddenly we find ourselves immensely bored of the standard litany of quarantine events, longing for an activity that is time-consuming but fun and rewarding. Baking bread is giving Americans a perfect yummy outlet for creative expression: it is iterative, so it rewards repeated trial and error; there are tons of new recipes to try; it is a fantastic virtual-social activity via zoom sessions with friends; and best of all, it produces a delicious medium for peanut butter consumption! Suddenly a new phenomenon has emerged—the so-called “bread boom!” [3] The prevalence of social media like Instagram has further encouraged new bakers to show off their creations and inspire their connections with the same great idea.

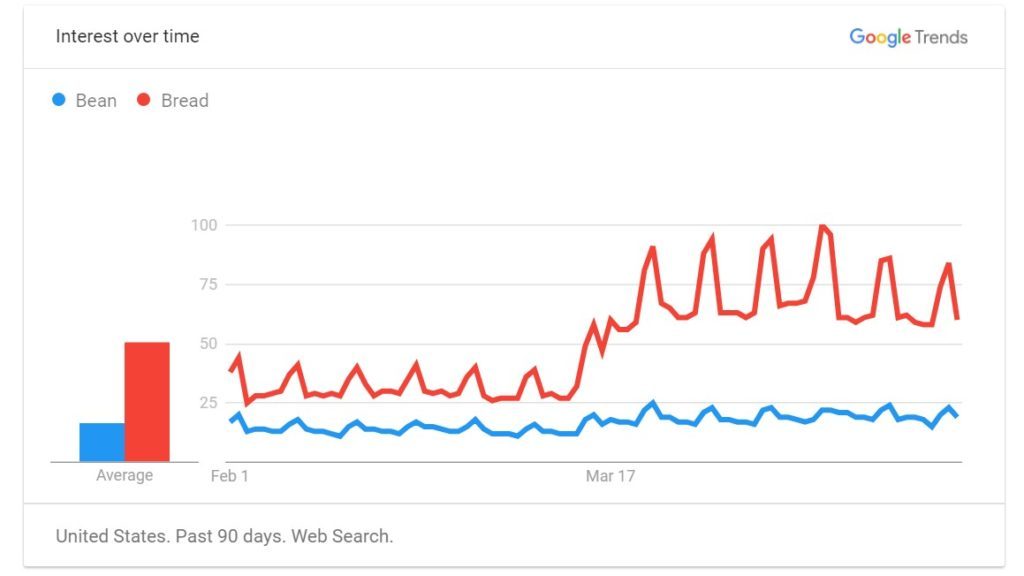

Google searches for “bread” have spiked [2]

With this sudden interest in home baking, who stands to benefit? It turns out that nearly all bread shares two common ingredients: flour and yeast. These essential ingredients have thus experienced huge surges in demand—flour demand has increased 155% and baking yeast 457%! While these industries are highly fragmented, it’s helpful to understand the problem by looking at some case examples. Kentucky-based Hopkinsville Milling Co. claims they are packing twice as much flour as normal. “It started to look like Thanksgiving and Christmas all rolled into one,” according to president Robert Harper. [4] Another mill which supplies flour online, Central Milling, is running all three production mills at maximum capacity despite COVID shutdowns. Still, it is hopelessly unable to keep up with suring demand. [4] Yeast supply showcases a similar story. Red Star, a major yeast producer, states on their website: “The current demand is simply unprecedented. Rest assured, we are making yeast around the clock.” [5]

While a surge in demand seems like a promising opportunity in any industry, the flour and yeast industry is struggling to keep up. As a fragmented commodity industry, classical price hikes in response to changing demand are impractical and result in consumer outrage. Thus, capturing value through increased prices is a risky proposition. Most producers have attempted to increase production in response, but the central problem is that these industries typically employ “just enough” production in normal time periods. They don’t possess a significant amount of excess production capacity because they must maintain efficiency in a narrow-margin business. Additionally, long production lead times make adapting to sudden changes in demand difficult. Fleishmann’s Yeast producer AB Mauri complains that “yeast takes a certain amount of time to go from one cell to two cells… there’s a hard limit to how fast they can double.” [7] Finally, the problem is partially rooted in operational norms. Many suppliers have traditionally shipped as much as 96% of their flour production in bulk to bakers and food manufacturers. In the UK, consumer consumption of these raw goods represents only about 4% of total production. [5] Thus, shortages are largely due to packaging constraints and established supply chain channels. Some producers are tackling this problem by shipping larger bulk packaged items through consumer channels, simultaneously relieving demand pressure and making available a product that satisfies panic shoppers.

This demand surge dynamic with constrained supply has had several prominent effects. One is a rapid flourishing of secondary markets. On Ebay, for example, flour and yeast prices are approaching 10x their normal prices, allowing secondary resellers to capture value from increasing consumer demand. Meanwhile, some consumers have sought substitutes such as grinding their own flour from seeds or using sourdough to replace the need for yeast. Some have even leveraged their existing skills in creative ways to harness this new demand. Danny Mayhugh, a photographer struggling for employment amid the pandemic, has turned to photographing his baking creations and selling them on Instagram! [8][9]

A creative combination of baking and photography skills leveraged into a new business [9]

Ultimately, surging demand due to both new interests and panic buying in a commodity industry puts a great deal of strain on supply chains, temporarily benefiting producers who can scale production the fastest or re-engineer their packing and supply chains in creative ways. The relevant question now becomes: will this demand last? Unfortunately, history indicates that panic buying often reverses once the fear catalyst resolves. Producers will likely only benefit short-term from scaling production unless the “bread boom” results in a lasting change in consumer behavior. Yet with millions of people discovering so many delicious new ways to enjoy a peanut butter sandwich, perhaps it will!

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/business/coronavirus-food-shortages.html

[2] https://www.eater.com/2020/3/25/21194467/bread-tops-google-trends-searching-for-recipes

[3] https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/fooddrink/bread-baking-coronavirus

[4] https://time.com/5819006/flour-shortage-coronavirus/

[5] https://redstaryeast.com/contact/

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/food/2020/apr/14/grains-flour-shortage-tells-us-about-who-we-are

[7] https://slate.com/business/2020/04/yeast-shortage-supermarkets-coronavirus.html

[8] https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/fooddrink/bread-baking-coronavirus

Super interesting! Personally I have been following the COVID cookery subreddit (https://www.reddit.com/r/covidcookery/) and it’s inspiring to see the foods that people have been able to create with their newly found free time. It will be interesting to see if this trend continues post-pandemic, and if so, whether there are market opportunities for companies that can make the production of these baked goods easier and cheaper.

Baking much bread through Covid-19, I am lucky to say I haven’t encountered any shortage of yeast or flour, in Mexico or Cambridge. Though I haven’t mastered sourdough or focaccia, I wish someone would accompany me in my process on zoom. If one thing Covid-19 has taught us is that technology needs to enter the sphere of distribution in the food industry, particularly in the space of perishables. If there is enough for everyone, why isn’t everyone getting it? Data insights into supply chains, and particularly into supply shocks are fundamental. If there is anything the bread trend is teaching, is that we need evidence-based decision through data analytics in distribution and supply chains.