The Business of Predicting and Winning Elections

How data brokers and cutting-edge social science have reshaped the modern political campaign.

It is well-known that political campaigns and social movements are becoming increasingly digitized and data-driven. The 2008 Barack Obama presidential campaign notoriously set the new standard for election forecasting and data-driven campaigning (there’s a whole book about it!), and the 2016 Donald Trump presidential campaign pushed the boundaries even further as campaigning moved online, developing controversial new “micro-targeting” methodologies to win an election over social media.

However, what is not talked about as much is the emerging commercial industry developing the technology behind winning elections. Who are these players, and how do they create value for political campaigns and social movements?

Arguably the most important digital asset underlying a political campaign is what is known as the “voter file” (or “base file”).

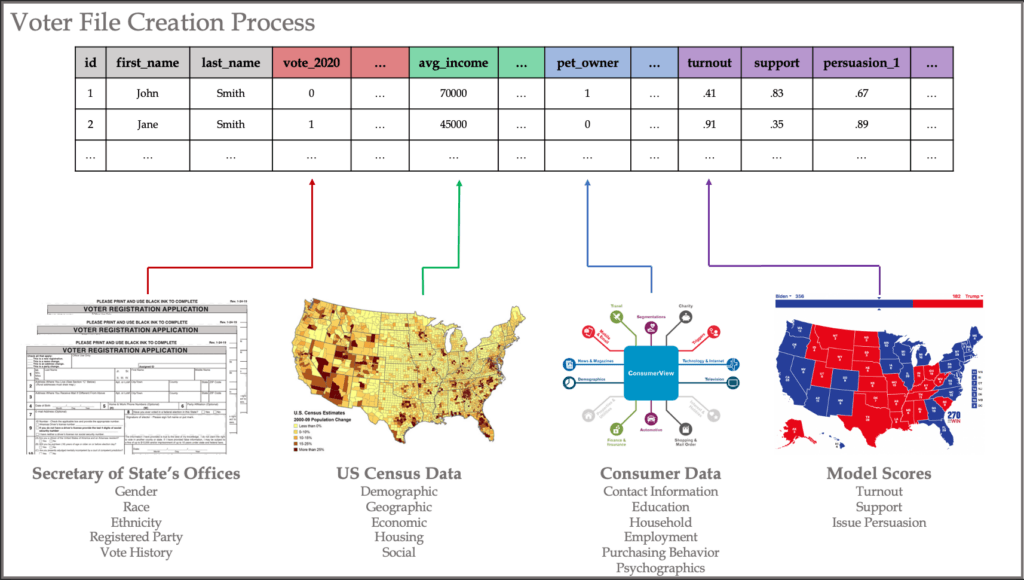

A voter file is the database of registered voters that underpins all technology and analytical methodologies in politics. The voter file is immense — merging numerous public and private data sources to compile thousands of data points on the almost 200 million registered voters in the United States. Public sources such as your state’s Secretary of State’s office and Census data provide data such as voter registration status, political party registration, demographic information, geographic information, and an individual’s voting history. Data from data brokers such as Experian or Acxiom can further provide known contact information, projected income levels, psychographics, and even purchasing behavior (everything from whether someone is likely to own a pet to whether someone purchases greek yogurt more on average).

The process to create and maintain voter files is a massive data engineering effort and requires the use of matching algorithms to merge person-level records from various sources.

Different companies provide voter files to each of the political parties.

The Republican Party (GOP) was the first to build a combined voter file in the early 1990s (15 years before the Democratic Party), though it wasn’t until 2012 until GOP-operatives developed The Data Trust, a for-profit company that determines which groups can access the GOP’s central maintained and enriched voter file.

In contrast, though the Democratic Party took longer to build such a voter file, the party’s enthusiasm for its need in the early 2000s was so profound that it actually splintered the market. Today two major voter file providers exist for the Democratic Party and Democrat-supporting organizations: Catalist and TargetSmart. The two companies compete on many points, including the accuracy and completeness of their voter file creation process and the data sources from which they pull to enrich the file.

Such an enriched file provides ample opportunities for analytics to help guide strategic and tactical decision-making on campaigns.

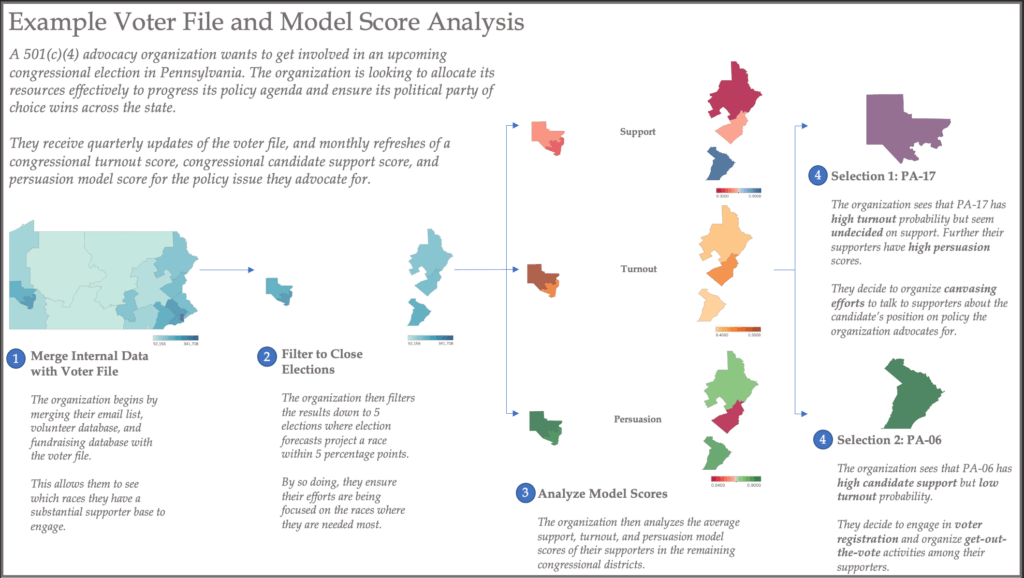

The most common analytical products produced for political campaigns are a set of three statistical models provided by companies such as Civis Analytics for Democrats and Deep Root Analytics for Republicans: turnout models, support models, and persuasion models.

A turnout model is an algorithm that produces a score between 0 and 1 that calculates the probability that an individual will turnout to vote in the upcoming election. A “0” score means an individual is highly unlikely to turnout to vote, and a “1” score means an individual is very likely to turnout to vote.

A support model is an algorithm that produces a score between 0 and 1 that calculates the probability that an individual will support a given candidate. A “0” score means the individual is highly likely to support the opposing candidate, a “1” score means an individual is highly likely to support your candidate, and a “.5” score means an individual is undecided.

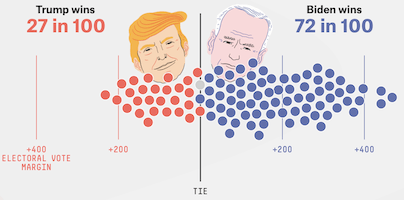

Together, the turnout and support models are combined to produce election forecasts for every race in an upcoming cycle, from the presidential race all the way down to state house races.

Finally, persuasion models are algorithms that produce scores between 0 and 1 that calculate the probability an individual will increase (or decrease) their support for your candidate given that they are aware of the candidate’s support for a given policy issue. For example, a climate change persuasion model with a score of “0” means that that the individual is likely to decrease their support of your candidate upon hearing their support for climate change, a score of “1” means that the individual is more likely to support your candidate upon hearing their support for climate change, and a score of “.5” means that the individual’s opinion of the candidate is unlikely to be moved based upon the issue of climate change.

These models are built by data scientists through a combination of historical data from voter files and surveys that are run leading up to the election. Analytics companies issue thousands of surveys a week to individuals on the voter file, asking them to indicate whether they are likely to turnout (for the turnout model) and which candidate they are likely to support (for the support model). Survey recipients are additionally placed through a randomized control trial (for the persuasion models) to see if their candidate support changes upon hearing their position on a policy issue.

Data scientists are then able to merge the survey results with the voter file and then train their statistical models. Upon completion of the model, they then score the rest of the voter file with their models, so each individual in the voter file receives turnout, support, and persuasion scores.

Political campaigns and advocacy organizations purchase these scores on a subscription basis, and processes are developed by the companies to refresh models as new survey data is completed leading up to the election.

The below demonstrates an example of how an organization might use the voter file to develop their election strategy.

The graph above captures how data and analytics have reshaped the modern political campaign. Recent campaigns suggest that these tactics will continue to evolve as technology and channels of communication evolve. Companies across the value chain have built sustaining business models to support campaigns and advocacy organizations, and are constantly innovating to continue to provide value for their political party of choice.

And yet, the new normal for modern political campaigning raises significant questions.

One question that comes to mind is the implication of the hyper-optimization of political campaigns that has occurred through these new data-driven methodologies. As voters and citizens, though we expect our representatives to speak to and for all of us, campaigns are continually narrowing their resources to a minuscule subset of citizens that tip an election one way or another. Is this the political system that we as voters and citizens desire?

Finally, perhaps the most discussed question of the day is one of ethics, especially in the wake of the 2016 Cambridge Analytica scandal, which involved campaign tactics that some referred to as “psychological warfare” on the American people. There is no question that the rise of political data and technology companies have created a new set of commercial gatekeepers between voters and their representatives, and there are very few restrictions on the way that political entities can acquire, share, and use data. Calls for the establishment of industry norms and privacy advocates will certainly shape the industry, and time will tell how the industry evolves to meet the changing environment.

References

Bland, Scott. 2021. “The Back-Stage Tech Tool That Knits Together All Of Democrats’ Data”. POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/12/15/back-stage-tech-tool-democrats-data-445485.

Cadwalladr, Carol. 2021. “‘I Made Steve Bannon’S Psychological Warfare Tool’: Meet The Data War Whistleblower”. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/data-war-whistleblower-christopher-wylie-faceook-nix-bannon-trump.

Desilver, Drew. 2021. “Voter Files: What Are They, How Are They Used And Are They Accurate?”. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/15/voter-files-study-qa/.

Issenberg, Sasha. 2013. The Victory Lab. Crown.

Lapowsky, Issie. 2021. “Data Firms Team Up To Prevent The Next Cambridge Analytica Scandal”. Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/political-data-firms-prevent-next-cambridge-analytica/.

“Leaked: Cambridge Analytica’s Blueprint For Trump Victory”. 2021. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/23/leaked-cambridge-analyticas-blueprint-for-trump-victory.

McDonald, Sean. 2021. “The Secret Power Of Political Data Trusts”. Overture Global. https://www.overtureglobal.io/story/the-secret-power-of-political-data-trusts.

Really interesting article Daniel! I imagine we are just scratching the surface in how data will continue to be used in politics. I think it is kind of interesting that political campaigns seem to be further ahead than the government in terms of digitization and data analytics – makes you wonder what these politicians are doing once they are in office!

Reading your post, I can’t help but think about how polling data and predictions was so tragically wrong in the 2016 election. How do you think these principles can be applied to polling, not just to campaign analytics? They seem very interrelated to me.

Yes! Honestly it’s a fascinating topic and a whole separate blog post could be written around challenges around political surveys/polling.

To your point — if your data collection is poor (i.e. your surveys are not representative of the voting population), then your turnout, support, and persuasion models will end up being poor as well — and lead to bad strategic decisions from the perspective of a campaign.

In short: Polling used to be phone-driven, but over time, the population of people picking up the phone and answering surveys were not the same as the population of people who weren’t picking up the phone — so a major trend of voters increasingly supporting the Republican candidate was being missed because these were the same people not answering phone calls. Hence support for the Republican candidate was significantly underestimated.

A ton of R&D work has been done since then to move the political survey infrastructure online, and forecasts have improved drastically since then (see 2018 and 2020 election cycles).

My former colleague did a great interview about what happened in 2016 — I highly recommend the below read for some deeper insight.

https://blog.newtoniannuggets.com/an-interview-with-david-shor-a-master-of-political-data-c2fa735731af

Holy Guacamole! There is an obscene amount of data collected, aggregated and used to predict voter outcomes. This is quite scary to think about. The implications on having free and fair elections and the impact on American democracy can be substantial. I guess, gone are the days when candidates tried to persuade with policy or rhetoric. With how polarized the nation has become, the independent voter has become far more important and thus this data becomes far more valuable. I hope this doesn’t turn into the most techy and well funded party (probably democrats although it appears that historically republicans have been ahead of the curve) always wins. That’s not good for democracy.

Do you think this kind of data collection and analysis is a net positive or negative for American democracy?

Yeah — great question! I think like many major technology innovations, the answer is: it’s complicated!

I do actually think there are many net positives here. I think the potential to truly understand national sentiment in essentially “real-time” is a net positive for American democracy. In particular, I think, if applied correctly, the infrastructure and analytic methods can provide our representatives with significantly more insight into the opinions of hard-to-reach and marginalized populations and how they evolve over time. Giving “voice to the voiceless” — if you will.

However, I definitely am with you that the unnecessary amassing of data on American citizens is not a net-positive, and as we’ve seen, in the wrong hands can lead to significant harm.

I am intrigued by recent conversations on industry norms that I posted above about data handling/governance.

I’m also pretty into the recent idea to make platform companies and data brokers into “information fiduciaries” — which could guide the decisions on how these companies would use data so that it is in the best interest of the people.

See below for more!

https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/10/information-fiduciary/502346/

Great blog post! While the power of data and targeting specific populations through analysis has clear benefits for campagins, I wonder if the interpretation of the data can be equally dangerous to politicians. To see voters as unlikely to likely voters and base importance of contact on this measure may reduce the importance of voice of many Americans. Will politicians and their teams become so laser focused on thed data and the tiny subset of most influential voters that they miss the forest for the trees and fail to learn what might change an unlikely to a likely? Do you think it is possible to become to myopic on data and groups that the data identifies as most important?

Yes this is a great point!

I’d even take it one step further — that if taken to its extreme, a campaign only focused on persuasion tactics could use these methods to only focus on the opinions of likely voters in strategic locations required to win the election. This usually comes down to a handful of counties in battleground states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Florida.

The reality is that campaigns usually don’t operate in quite an extreme — and usually persuasion and turnout (getting voters don’t typically vote to turnout) tactics are seen as necessary to win an election.