Spacehive: Crowdfunding Civic Projects in Great Britain

Spacehive democratizes urban planning by funding projects directly through the crowd.

Platform model

Spacehive is a British crowdfunding platform that funds civic projects that improve neighborhoods and public spaces. It seeks to “make it as easy as possible for as many people as possible to bring their civic environment to life.” Former architecture and urban planning journalist Chris Gourlay founded Spacehive in 2011 because he wanted to democratize urban planning, which he felt was held back by the “merry-go-round of planning meetings, consultations, fundraising rallies and paperwork.”

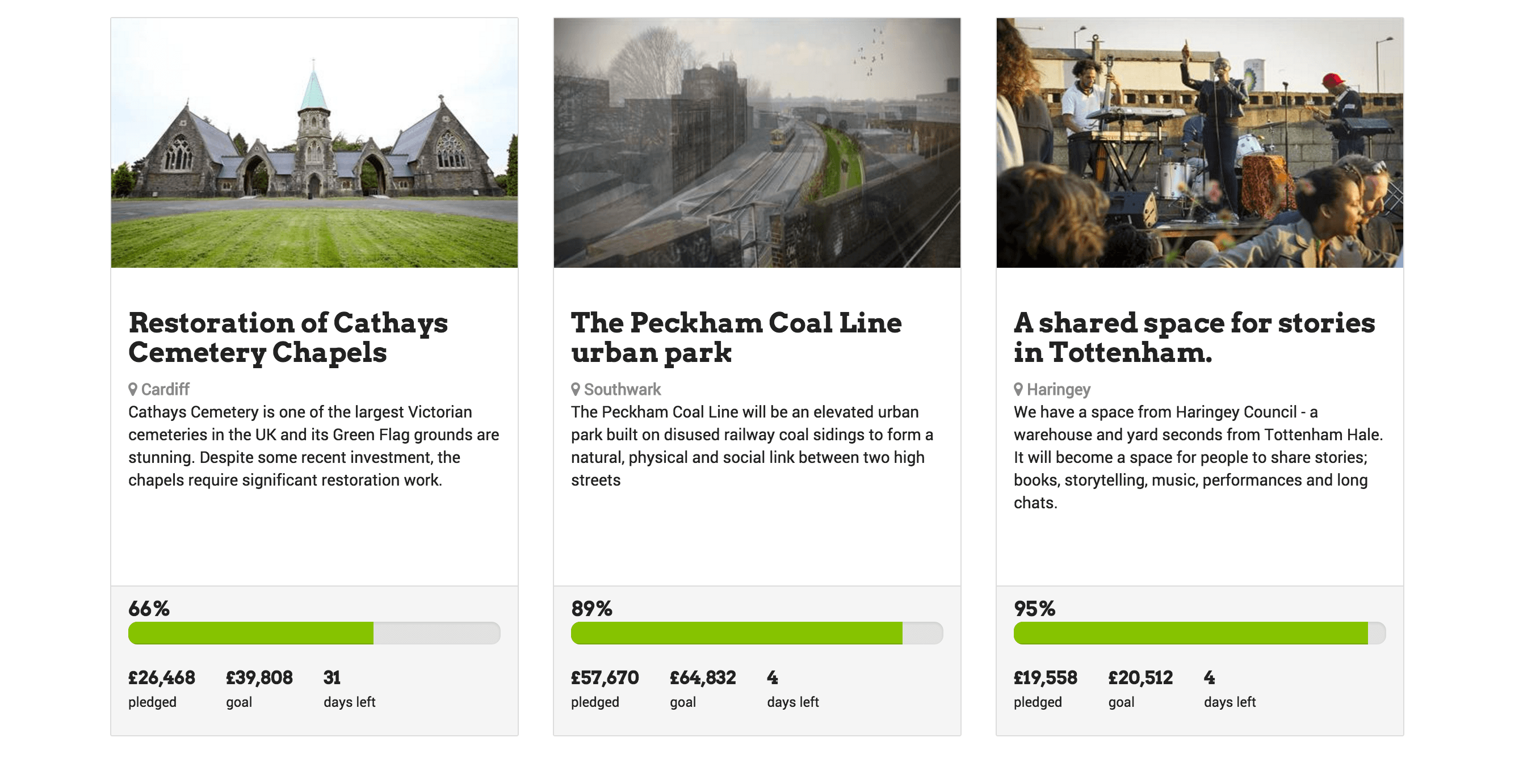

Spacehive encourages all project types—big and small—to use its platform. To date, the total value of funded projects is £3.8 million, with the average value of a project at £28,500. Previously funded projects include a community center in South Wales, a collective artists space in Croydon, and a papier mache Queen’s Head for a parade.

Here is how the funding process works:

- Anyone can login and create a project page, which entails describing the project in detail, identifying the location, and selecting the fundraising target and deadline.

- Spacehive approves the project.

- Spacehive posts the project.

- Users view projects by type, city and neighborhood and choose which ones to fund.

- If the project reaches its fundraising goal by its deadline, then the project is funded. Like Kickstarter, Spacehive uses an all-or-nothing funding model; projects that fall short of their goal are not funded.

Spacehive also allows users to create hives, which are incubators for projects that “work by connecting project creators with communities of likeminded supporters—from local people to companies and councils—that want to make things happen”. There are now 35 hives on the platform, and are typically set up around a neighborhood or idea. For example, there is a Save Santa hive that collects Christmas themed projects. There is also the #MakeMCR hive, which focuses on projects to improve Manchester. Check out the video below on #MakeMCR:

Revenue model

Spacehive makes money through a series of fees. Although it is free to create a project, successful projects are charged a 5% commission fee (Spacehive adds the commission fee to the overall project cost so the crowd ends up paying the fee). There is also a small transaction fee for successful projects; this fee changes for each project. For example, a project funded by 10,000 small donations will have a higher transaction fee than a project funded by a single large donation. Spacehive also charges £2,000 + VAT a year to maintain a hive.

Incentives

Those who contribute to projects on Spacehive are motivated by the desire to enrich their own community. The projects affect their day-to-day lives, so it does not matter that they do not receive a physical product or equity in a company like on Kickstarter or Indiegogo. Spacehive leverages community to create a sense of ownership amongst the crowd. It is rewarding, for example, to walk by a park in your neighborhood or attend an arts festival that you helped fund. Additionally, there is no minimum donation and many project goals are small, so users still feel like they are making a difference even with a small amount.

Spacehive also incentivizes participation through corporate and government partners that match the money raised by the crowd for each project. These partners include Experian and the Mayor of London.

Challenges and growth

Going forward, Spacehive must maintain a good relationship with local governments. Spacehive in a way subverts local governments by going directly to the crowd to fund projects, yet it also must work with local governments to implement projects once they are funded. Therefore, it is essential for Spacehive to work hand-in-hand with local governments and emphasize its positive role in local communities.

Another challenge for Spacehive if it wants to grow is increasing the amount of projects on the site. In theory the crowd should be motivated by the desire to improve their neighborhood, but many users are busy and would rather contribute to instead of create a project. One way to incentivize project creation is to create a prize or reward for the creator if the project is fully funded.

It is intriguing to see a successful application of crowdsourcing to mobilize community involvement. Your post is an interesting complement to my post titled “Let’s Crowdsource the Constitution!” that deals with the question whether it is possible to crowdsource more complex decisions at the national level. As an example, I analyze a failed attempt to crowdsourced constitution in Iceland.

The success of Spacehive vis-a-vie the failure in Iceland allows to identify some key lessons for community crowdsourcing campaigns:

• Crowdsourcing is not best suited for complex, multi-step processes. Focus your campaign on a clear target with a defined timeline.

• Tackle projects on a local/regional scale rather than large national issues; do not underestimate the volume and complexity of data that would need to be processed.

• Limit the number and/or format of possible inputs.

• It is a partnership: crowdsourcing local projects in cooperation with local governments could be a win-win deal (think public-private partnerships, or PPP). If local governments are the gatekeepers, get them involved.

I question, however, the speed of the platform’s expansion and its scale. Despite being live for the last five years, at £3.8 million of total funded value the scale of Spacehive is still rather insignificant. I wonder whether greater involvement from governments or a different fee structure could help the platform to scale. One idea could be for governments to use Spacehive to communicate with local communities on regular basis, something like a local virtual bulletin board. That would potentially increase the number of users and could create positive network effects.

I’m really interested to look into this to find out the geographical spread of projects and how that compares to wealth. I can see a world in which the regions which need the most projects also are the poorest, and therefore no-one from these areas has the disposable cash to invest.