Has a Winner-Take-All Strategy Failed Instacart?

With $220M in VC funding, Instacart was poised to become the premium grocery delivery platform. As it's model shows cracks two years later, I wonder if a Winner Take All strategy was appropriate to its business.

Imagine how Aproova Mehta must have felt in the summer of 2015. His company, grocery delivery service Instacart, had just raised $220M in venture funding, more than twice the funding of other food delivery services, like Fresh Direct ($91M), Hello Fresh ($68M) or Blue Apron ($58M) [0] Mehta could now pursue a winner-take-all strategy, using his heap of dry powder to buy the customers and shoppers he needed to create the next great platform; the Uber for grocery delivery.

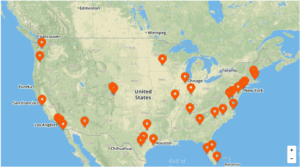

Over the next two years, Instacart grew rapidly into new geographies, adding tens of thousands of shoppers and many more customers (see map below) [1]. To offer value to customers, they offered the same prices as customers would get in stores, and collected only a modest delivery fee (typically $3.99). To attract shoppers, they offered generous opportunities to make money; “up to $25 per hour,” they would claim [2].

Recently the model has shown cracks, however. In 2016, Instacart cut pay for frontline workers by up to forty percent [3], while simultaneously warning workers that it reserved the right to further cuts. They simultaneously removed tipping from their billing options, replacing tips for a standard 10% service fee which they claim is redistributed to shoppers (this claim is contested).

Since eighty percent of shoppers received tips prior to the change, the switch put significant strain on Instacart’s relationship with its shoppers, who have many alternative homes for their on-demand labor. Workers believed the change was a straight-forward attempt to make the business more profitable, but the change could also reflect the need to create revenue growth. Whereas tips cannot be reported as revenue, service fees can.

Meanwhile, despite piling tons of cash into the space, Instacart has hardly gained a competitive edge. For customers, Instacart’s service is essentially undifferentiated from other options. In Boston, for instance, the same basket of 10 groceries can be delivered by Peapod, Amazon Fresh, or Instacart for about the same price, at about the same time. Each service offers grocery-store prices, a $5-10 service fee, and delivery within 24 hours depending on the day of the week. This is especially notable because Peapod has been around since it was founded in 1989 [4], and Amazon Fresh is an entirely new service still in its infancy. If Instacart cannot differentiate itself from long-standing incumbents or recently upstarts, it is unclear what its $220M investment is worth.

| Service | Food Cost | Delivery Fee | Other charges | Total cost |

| Instacart | $63.92 | $3.99 | $6.39 (10% Service Charge) | $74.30 |

| Peapod | $65.34 | $9.95 | $0 | $75.29 |

| Amazon Fresh | $58.07 | $0 | $5.88 (amortized annual fees) | $63.95 |

Elsewhere competition is growing in quickly. Grocery delivery services are popping up in virtually every imaginable geography, whether in Colombia (Merqueo), Australia (Grocery Butler), the UK (Grabfood), Russia (Zakaz), Singapore (RedMart) or India (PepperTap). More concerning has been the proliferation of are local rivals, like Grocery Works of Dallas, Urban Essentials of Oklahoma City, and largest of all, Shipt, which has grown throughout the Southeastern US. The emergence of so many competitors suggests barriers to entry are relatively low.

| Grocery Delivery Services | |

| Service | Geography |

| Instacart | USA |

| PepperTap | India |

| RedMart | Singapore |

| Conershop | LatAm |

| Instamart | Russia |

| Zakaz | Ukraine |

| Grabfood | UK |

| Grocery Butler | Australia |

| Burphy | Texas |

| Shipt | USA, SE |

| Uban Essentials | OK City |

| Merqueo | Colombia |

| Grocery Works | Dallas |

| Source: CrunchBase | |

There is a more critical difference between grocery delivery services and ride sharing than barriers to entry, multi-homing or network effects, however, and it may offer a more plausible explanation. Whereas ride sharing apps offer customers an improved version of a taxi service—a service they already are accustomed to using—grocery delivery services ask customers to do something new. The difference may appear subtle at first, but they are important. Most people buy groceries when they need them. Some folks know what they are going to buy, but many are making decisions at the store. Groceries are frequently a budget item which invites economizing. Grocery delivery services require customers to (a) plan what they want in advance, (b) choose between alternatives online, instead of in-person, (c) plan when they’ll need groceries so that they can be delivered on time, and (d) be willing to pay an extra $10 to get their groceries. However convenient grocery delivery may be, these new habits take time to develop.

The point is that whereas customers could quickly snap up Uber and understand how to use the new service, grocery delivery requires a bigger leap. This means building a successful platform is likely to take longer as customer behaviors evolve. In this world, piling hundreds of millions of dollars into a national expansion could actually be a wrong strategy, because by the time customers come around to trying your app, you’ve already burned your resources. Instead, building a profitable business with strong regional competency–like Peapod, and more recently, Shipt–could be a safer approach. This, however, isn’t the type of business that Kleiner Perkins leads a round of $220M for. Now it appears Amazon Fresh will eat Instacart’s lunch. As others have pointed out, sometimes in the platform world growing rapidly to be the first mover can have its costs [4].

[0] http://blog.datafox.com/7-instacart-competitors-grocery-meal-recipe-delivery/

[1] https://techcrunch.com/2016/10/14/instacart-reverses-course-re-introducing-tips/

[2] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/02/instacart-workers_n_6548822.html

[3] http://www.cnbc.com/2017/02/20/instacart-is-playing-games-with-its-workers-pay–and-will-eventually-suffer-for-it.html

[4] https://hbr.org/2016/04/network-effects-arent-enough

Thanks for the post, James. Some other challenges that Instacart faces has to do with managing the customer experience. More specifically, because Instacart doesn’t have up-to-date line of sight into inventory levels, customers sometimes don’t receive their complete order. If they’ve placed an order to make dinner that evening and the protein is missing, then what’s the point? Another grocery trip is needed. Competitors, who own the inventory like Amazon, Peapod, and Jet, can ensure fewer stock outs and have an opportunity to earn better margins if they manage their spoilage rates effectively. Additionally, having independent contractors and a lack of consistent fulfillment procedures opens the company up to quality and liability issues (e.g. broken eggs and raw meat that hasn’t remained within the appropriate temperature range). I’m curious to see how Instacart will try to overcome these challenges.

Interesting post James. Thanks! Lauren I completely agree with your point on customer experience but I think Instacart’s 1-2 hour delivery is definitely a competitive advantage. It entirely eliminates the need to plan in advance, most of the time I am happy to trade the risk of missing items for the convenience of getting my groceries in under 2 hours. I can see this being a pain-point however for other customer.