This post was originally published in the HBS Alumni Bulletin.

In a lot of ways, it didn’t seem like a very good experiment to run.

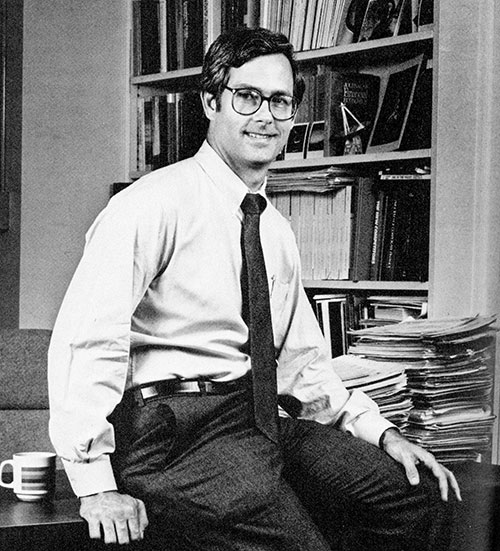

A young HBS professor—a rising star in the Finance area, an economist by training, by then already looking down the road at an all-important tenure decision—had an idea for a novel second-year MBA course, in which he would combine then-emerging thinking at HBS about entrepreneurship with some new kinds of financial strategies he had been roughing out.

Entrepreneurial Finance seemed like a logical name for the course.

Almost nobody up the food chain from Bill Sahlman offered much encouragement. Entrepreneurship is like an intellectual onion, one of his Finance advisors told him. You peel it and peel it, it makes you cry, and there’s nothing in the middle. There were some exceptions to this institutional indifference, including Sahlman’s mentor on the faculty, Howard Stevenson—himself the spark plug behind the School’s recent push into entrepreneurship. And behind Stevenson was Dean John McArthur, quietly determined to steer the School into the tempting but elusive field of new ventures, and willing to back people who were brave enough to serve as the point of that spear.

A second senior advisor delivered some further bad news. The higher the teaching ratings you get, he told Sahlman, the more likely you won’t be promoted.

Come again?

Entrepreneurship is amorphous. It’s storytelling. And storytelling is extremely popular with students, but so too would be a course on how to manufacture LSD. You can’t get traction. Just don’t go there.

Sahlman was daunted, but he wasn’t dissuaded. He had some momentum. He had been writing cases and notes on entrepreneurial ventures since his arrival at the School in 1980. But all along, that had been a solo effort, and as a result, he had nowhere near enough material for a full-credit course. So he decided to offer a half-credit course instead—15 sessions rather than 30.

There was always the risk of embarrassment: Maybe no one would sign up.

On the other hand…

Sahlman knew for a fact that whenever one of his colleagues offered a course that focused on people in a deal-making context, students signed up in droves. That had been true for the real estate courses that Howard Stevenson and practitioner-academic Bill Poorvu had taught in recent years; it had been true for the Starting New Ventures course that former faculty member Pat Liles had run years earlier; it had even been true for some of the less-than-compelling entrepreneurship courses that had been offered in the recent past. Even when the supply faltered, the demand never went away.

And in the year that was just ending, Sahlman had taught first-year Finance to some 180 students—two sections of 90—who had rated him highly as a teacher. This wasn’t always the case. “Let’s get that on the table,” he recalls with a typical wry grin. “My first two years at HBS, I was the lowest-ranked Finance professor.” But since then, he had gotten better in the classroom—way better. His student ratings had improved dramatically. Surely some of those 180 satisfied customers, now choosing their second-year electives, would humor Professor Sahlman and sign up for his adventurous new course.

Wouldn’t they?

Sahlman believed he had a conceptual structure for the course that might protect him from the dreaded Onion Outcome. “My goal from the beginning,” he recalls, “was not to dump all of the economics and become a storyteller—I had been warned about that!—but rather to create an economic analytical framework that made sense.” As a starting point, he drew on Poorvu’s and Stevenson’s prior work, which focused on four elements: people, opportunity, context, and deal. To that framework, Sahlman added a notion of dynamism—change over time—that underscored the changeable nature of all the component parts. “In other words,” he explains, “who can add what elements to the mix to increase the chances of the venture succeeding over time? And conversely, what can be done to stop things from going wrong and getting yourself kicked out of the game?”

Sahlman cites the famous example of Jobs and Wozniak at the birth of Apple Computer. “Were they the right guys to create a hand-assembled computer motherboard company in 1976?” he asks rhetorically. Answer: sure. But—were they the right guys to build a major personal computer company? No. That only became possible when, at the insistence of the venture capital community, former Intel executive Mike Markkula joined the team.

“So in that way,” Sahlman continues, “it’s different from real estate. It’s about, how do I create experiments that reveal to me, and to people outside the management team, that this makes sense and is going to succeed? It’s a multi-period, high-uncertainty-that-needs-to-be-resolved kind of process.”

Sahlman’s revised framework soon proved a useful tool for understanding the seemingly chaotic world of entrepreneurial finance: “It captured what I was seeing in the world of practice,” he says. “And it stood up to the take-something-away, add-something test. Which of those building blocks could you live without? None. What would you add to make it more complete? I still haven’t come across that missing piece.”

So with a field-tested framework in hand, Sahlman launched his course in the spring of 1985.

In theory, there were 200 available seats. That was nowhere near enough for the 450 students who signed up. And who signed up in droves the following year—requiring the teaching of two additional sections by Sahlman’s senior colleague Warren Law—and the year after that, and the year after that. By 2017, some 10,000 students had taken the course. Beginning in 1999, moreover, every first-year HBS student has taken a required first-year course called The Entrepreneurial Manager, which draws heavily on the content of Entrepreneurial Finance. And this past year, Sahlman—now retired, and several years away from the Entrepreneurial Finance classrooms—launched an online version of the course through HBX, attracting students from around the globe.

The experiment, as it turned out, was well worth running.

He was, by his own admission, “an overeducated economist” who greatly enjoyed the economist’s normal pastimes of rummaging through data sets, crunching numbers, and testing theories.

But one day, he found himself hung up on the opening line of a teaching case: DuPont was considering entering the titanium dioxide market. Sure, there was some contextual material, as well as reams of financial projections focused on a proposal to build a titanium dioxide plant. But there were no people in the story. “Not even any DuPonts,” Sahlman laughs. “Long dead. Long gone.”

Here, Sahlman interrupts his own train of thought. “Hey,” he says, “it’s a fine case, cowritten by a close friend of mine, Carl Kester. He takes some offense when I beat up on it. Sorry, Carl!”

Sahlman’s perspective was influenced by his father, a successful manager who had dealt with similar kinds of resource allocation issues. Sahlman knew that in such circumstances, his dad had always concentrated on finding the right people. “Meanwhile, at HBS we were teaching what I called ‘neutron bomb’ cases,” he recalls. “Lots of numbers, no people.”

There was more. Many finance cases at the time focused on pricing securities and pricing risk. “In finance,” Sahlman says, “we hold the view that you only get compensated for bearing non-diversifiable risk—in other words, what’s left over after you take all of these disparate projects and throw them in a single portfolio of every risky project in the world. And yet, everywhere I went, venture capitalists were using high discount rates, and it wasn’t clear how that related to risk. Here’s a bunch of people giving money at 50 percent to projects that really should only be charged 10 percent. Well, if markets work correctly, after a little while people will come rushing in, bidding up the price of the project so that they’ll only earn the 10 percent. That’s how markets work, right?

“But the fact was, no one was rushing in, because those venture capitalists weren’t actually using 50 percent discount rates,” he continues. “They were simply trying to reflect the resolution of uncertainty. They were saying, ‘Well, if a lot of things went right—that is, a single scenario among many that were likely—then I could discount the success scenario back to the present, and make a rational decision.’ So it’s really quite a different thought process, and it suggests answers to a whole bunch of questions beyond just the high discount rates: Why do they always use convertible preferred stock? Why do they stage the commitment of capital? Why do they intervene and try to be helpful—or in some cases, screw things up?

“So our thinking got sharper. Yes, from whom you raise money can be as important as the terms—but the terms matter too, because you’re in a multistage process where winning at each stage doesn’t matter. It’s winning at the end, not at each point.”

People, opportunity, context, and deal, changing iteratively over time. Sahlman cites a contemporary example: the Casper “bed-in-a-box” foam mattress company that launched in 2014. “Suppose I come up with an idea for a foam mattress I can stuff in a box and ship directly to customers. Well, there’s a lot of uncertainty in that project, right? I don’t know if I can make the mattress. I don’t know if people will buy it online without trying it out first. I don’t know if I can stuff it in the box. I don’t know if the postal service will deliver the box. I don’t know a lot of stuff, right?”

And what about those pesky people, in Sahlman’s conceptual framework? Sahlman likes to point to the example of Mitch Kapor, whose résumé in the early days—if indeed he had one—would have reflected an extended college plan, two years as a disc jockey, a year teaching Transcendental Meditation, and several years earning a degree in counseling and working in a hospital outside Boston. Then Kapor cofounded Lotus Development, the company that developed Lotus 1-2-3, which crushed VisiCalc, which was the ur spreadsheet company that had helped make the Apple II a viable business tool.

What classical economic model could have predicted that?

“It was assumed,” Sahlman says of the theory that he was increasingly inclined to challenge, “that the people involved were rational decision-makers, that the markets all worked, that everybody had access to the same information, and that there were no transaction costs. None of which, of course, applied in the world of ventures.”

Uncertainty and the unknowable, moving in risk-filled directions, all at a fast clip. Says Sahlman: “All I was trying to do was to understand, How do entrepreneurs make decisions? How do the people who give them money make decisions? Does it matter who starts it? Does it matter who funds it? How does it evolve logically over time? What insights could you derive from studying that particular set of circumstances, where there’s lots of uncertainty and lots of agency problems, meaning that one group may not behave in the best interest of the other group? How do they structure contracts? More fundamentally, why would anyone ever invest in this area, and why would anyone in the world of entrepreneurship ever bear the enormous personal risk associated with the process? In fact, it was less about entrepreneurship and more about decision-making.”

So Sahlman—first alone and later with several junior colleagues—undertook to understand decision-making both on the entrepreneurship side and on the financing side. He soon started seeing interesting patterns. The entrepreneur got a little cash somewhere—maybe from friends and family, maybe from an investor—and ran a structured experiment aimed at learning something specific. If the experiment was successful, maybe another group of investors gave the entrepreneur a little bit more money to run another experiment. In other words, it was an iterative and disciplined process, which continued until the startup failed, changed dramatically, or succeeded.

This realization, in turn, led Sahlman to focus on execution—the proving ground for people, opportunity, context, and deal. For example, he wrote about the contrasting implementation strategies of Ovation Technologies and Lotus Development, allowing his students to get a handle on why getting financing through software-industry guru Ben Rosen (Lotus) led to a different and more effective execution than getting end-of-tax-year money from Chicago-based commodity brokers (Ovation). He also wrote notes providing deep industry and sector background for the software cases (and in the process, helped shore up his traditional academic credentials). And not least, Sahlman persuaded both Tom Gregory and Mitch Kapor—the heads of Ovation and Lotus, respectively—to come to class when their cases were being discussed. Students in Entrepreneurial Finance knew that, as they struggled to understand why the protagonists acted as they did, they might soon be getting the answer firsthand.

Consistently, Sahlman tried to focus on what he calls the “fomenting attack”—that is, the agent of change that was attempting to change the rules of the game and disrupt an entrenched player: Amazon vs. Barnes & Noble, Uber vs. the taxi industry, and so on. “Our cases were necessarily snapshots,” he emphasizes, “but we knew we really needed to be in the moving-picture business. Change, change, change. We had to rewrite old cases and write new ones, constantly.”

It was a labor of love that continues today.

The entire US venture capital industry added up to a mere $1 billion or $2 billion back in the early 1980s—“kind of a rounding error,” Sahlman observes—whereas today, it’s a hundred times as big, with additional trillions of dollars sloshing around in private equity and other pools of funds. Meanwhile—as both a cause and an effect—an enormous entrepreneurial revolution has been unleashed. More and more people have access to more and more money to try out more and more ideas.

So yes, money talks—and loudly. But the revolution also has psychological aspects that are harder to quantify and equally profound. As a society, and certainly in the business class, we’ve come to think about entrepreneurs differently. “Today,” Sahlman says, grinning, “the implications of failure are de minimis. Assuming that you didn’t lie, cheat, or steal, or personally cause the collapse of the venture, you can fail and get away with it. In Silicon Valley, you fail, and you don’t even have to change parking spaces. You just go back into the building, new company, and your Herman Miller chair is still there. And you’re not called a failure. You’re called experienced.”

And certainly, Sahlman and his colleagues can claim some share of the credit for that revolution. They thought systematically about a phenomenon that didn’t seem to lend itself to structuring—and succeeded. They immersed themselves in a world in which every single deal was unique—and almost by definition, unprecedented—and figured out some underlying dynamics that explained, and sometimes even predicted, success and failure.

Not an onion, certainly. Maybe an avocado: a fruit with a skin that seems tough but still allows for easy bruising by outside forces, with a certain amount of highly perishable reward below—depending on whether you choose well in the first place—and a core that promises growth and renewal.

Depending on whether you grow it right.

Takeaways from Entrepreneurial Finance

Each of the 10,000-plus veterans of Entrepreneurial Finance has his or her own list of lessons learned in the course. Here are just a few:

Cash is king. More cash is better than less cash. Cash now is better than cash later. Less risky cash is better than risky cash. Don’t run out of cash!

Use your cash to get smart. Use your resources to buy time to structure tests that reveal value-changing information. What can go right? What can go wrong? How can you manage reward and risk?

Hone the deal. Who gets what amount of cash at what time? How is risk allocated? What are the incentives of all parties to the deal now and given reasonable scenarios into the future? Who will be attracted by the deal? What can be inferred from how people respond to the deal terms? What are the future consequences (at all levels) of current decisions?

Pick great people. Who among your potential co-venturers is skilled, flexible, and honorable? How can they help when smart VCs pay more attention to the team than to the initial value proposition. Build the team that will buy you credibility—and of course, get the job done.