Why Real Estate Brokers Exist in 2016 And Beyond

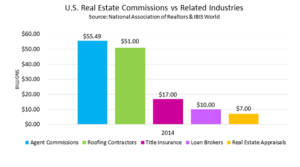

Real estate brokers always seem to be the next industry ripe for disruption, yet the profession remains stubbornly resilient. The Internet, smart phones, satellite mapping, virtual reality, secure online payments, and consumer data access have all impacted the real estate search and purchase process. However, the broker fee is still the most expensive transaction cost. The median rate has barely budged from the historical 5-6% of purchase price for selling and 15% of annual rent for brokered rentals in New York City.[1]

Why hasn’t technology disintermediated the real estate agent? Is there an execution failure from all the companies, or is there a more underlying issue that makes brokers harder to disrupt than meets the eye? Why do we still need a human agent when transacting real estate, but not for trading stocks, booking flights, or reserving restaurant tables?

RentHop, an apartment search marketplace founded in 2009 [2], started with the premise that real estate agents were no longer adding enough value to justify high transaction fees. Three years later, after many business model pivots and skirmishes with the brokerage industry, RentHop finally embraced the real estate professionals. Today, this company and a slew of peer competitors earn a majority of their revenues matching buyers to brokers.[3][7][14]

What Does a Broker Do Today?

To analyze the potential digital transformation of the real estate industry, we first decompose and group broker services by potential for technology disruption.

Easy to Automate

- Interview and survey buyer preferences

- Determine buyer qualifications against seller requirements (max budget)

- Research historical data for pricing

- Gather required buyer documentation

- Coordinate related parties (lender, lawyer, inspector)

- Filter inventory to find suitable matches

The above items are considered low-hanging fruit and “easy” to automate. Numerous tools and services already exist to perform the above tasks. However, a first-time home buyer still needs to know which website or app to use, and learn how to properly use it. For each new technology that enables consumers to analyze real estate more effectively, it adds to a list of skills expected from a seasoned professional. For those unwilling to invest the time to research the latest resources, the agent becomes even more valuable!

Possibly Automate, with Caveats

- Find potential customers

- Spot good deals and match them with reliable customers

- Advertise the listing on the most relevant channels

- Aggregate listing information sources and keep them up-to-date

- Schedule the tour, meet buyer, and gain access to the space

Some tasks are easy to automate in theory, but two decades of innovation have not yet shown promising results. Marketing platforms are always changing at the rate of technological innovation, and real estate agents seem best at evaluating and adopting to the latest trends (and we see lots of variability in skill of adoption [11]). Are humans or machines quicker about switching to the next new mobile, social, or virtual reality advertising platform? [14]

On the scheduling frontier, every year dozens of new startups launch hoping to be “the OpenTable of real estate.” The plan is to aggregate all the sellers and agents in town, post the inventory with available showing times, and have buyers schedule viewings without dealing with a human (maybe a low-cost assistant shows up for the touring portion to represent the seller).[8]

The analogy has two major flaws: The stakes are vastly different when shopping for dinner home for the next many years. More importantly, a restaurant customer is very likely to show up and purchase food. However, a customer who tours an apartment only has a very low probability of transacting (agents show homes all day long and are happy to complete just a handful of deals per quarter). The low conversion rate makes the economics of a broker model more desirable for sellers to seek help. Many agents schedule many showings in a crowd-sourced fashion, but only one winner receives a commission check.

Difficult to Automate

- Observe customer reaction and adjust search parameters

- Convince buyers to submit offer

- Navigate the negotiation process

- Convince client to sign and close

The true challenge acknowledges that finding a home is as much an emotional decision as it is quantitative. Individuals have unique utility functions, yet can’t articulate or understand all the components (often making irrational decisions in the heat of the moment). A skilled agent carefully re-evaluates the search during their interactions through a series of explicit questions (what did you think?), passive observation (looks like the small kitchen turned her off), and deduction of revealed preferences (I wonder why this house excites them). The agent decides whether to make significant adjustments to the search, or in extreme cases, politely cease working with the client.

The extreme variability in broker incomes also suggests that client interactions require skill and are not merely a commodity. In most US cities, the median agent earns between $30,000-$50,000 a year while top agents earn over $200K (in high-demand markets, the dispersion can be 10x or more). Among the many explanations for earnings variability, the most important difference is the agent’s closing rate — the number of houses sold or leases signed per year.

For now, brokers can distill for us a process that so far hasn’t been properly captured in a database schema, a block of text, a set of photos, or even a virtual reality tour. (Word Count: 797)

[1] US Department of Justice: Competition in the Real Estate Brokerage indsutry

https://www.justice.gov/atr/competition-real-estate-brokerage-industry

[2] RentHop (Wikipedia)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RentHop

[3] Getting the Agent Without the Fee

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/realestate/08rent.html?_r=0

[4] RentHop: Easier Apartment Hunting Without the Broker Fee

https://techcrunch.com/2009/07/11/renthop-easier-apartment-hunting-without-the-broker-fee/

[5] Want to Disrupt an Industry? Try Actually Working In It First

https://www.fastcompany.com/3001334/want-disrupt-industry-try-actually-working-it-first

[6] RealtyHop Helps Investors Find Underappreciated Rental Properties

https://techcrunch.com/2015/05/20/realtyhop-helps-investors-find-underappreciated-rental-properties/

[7] With Revenue Tripling, RentHop Makes Apartment Search Smarter

http://www.forbes.com/sites/petercohan/2012/12/20/with-revenue-tripling-renthop-makes-apartment-search-smarter/#37d3bf5177ec

[8] Oliver, A New Apartment Finding App Cuts Out The Middleman

https://techcrunch.com/2015/07/28/oliver-a-new-apartment-finding-app-cuts-out-the-middlemen/

[9] Inman News, Real Estate Agent Salary: High-tech Agents Lead the Pack

http://www.inman.com/2012/02/14/survey-high-income-real-estate-agents-lead-pack-tech/

[10] National Associate of Realtors, Field Guide to Working with FSBOs

http://www.realtor.org/field-guides/field-guide-to-working-with-fsbos

[11] NYC Broker Leaderboard (timely response rate to online inquiries)

https://www.renthop.com/nyc_broker_leaderboard

[12] Real Estate Commission Explained, Revealed, and Compared

https://www.besmartee.com/blog/real-estate-commission-explained-revealed-and-compared

[13] Real estate has always been a two-sided marketplace, but the costs of multi-homing are very low relative to the size of the transaction ($500K house for sale vs. $20 to advertise in another unsaturated channel). Brokers earn commissions on closed transactions and are highly motivated to try any new channels if there is a reasonable chance of gaining a marketing advantage.

[14] Zillow, RealtyHop, Trulia, PadMapper, StreetEasy, RentJungle, and Zumper are among many competitors that also began with aspirations of eliminating the need for brokers only to capitulate later into becoming an aggregation portal of broker offerings.

[15] Apartments for rent in New York City and Boston are among the few markets with open listing rentals. The landlord does not grant an exclusive right to one broker, but crowd sources the tenant search process to all licensed agents who must find customers and collect commissions at their own expense.

Lee, interesting that you know so much about renthop… The interesting thing about broker automation is that we haven’t been able to “unbundle” the broker’s tasks. For me, the main reason that I used a broker when purchasing my house was to make sure there wasn’t something I was missing about the value of the house. Basically to make sure I was getting a fair price. I needed that assurance to convince me to pull the trigger on such a large purchase. Most of the other broker tasks, like generating a list of potential houses, researching historical prices, etc, can be automated, and just need to be “unbundled” from the negotiation process. Going forward, sites like renthop that can just offer an “expert” to close the deal once the majority of the process has already been automated, will have a huge strategic advantage, since there is no reason that those expert needs to earn the same level of commission since they are performing far fewer tasks.

The unbundling approach is interesting and has been tried many times by startups (some dead, some still alive, but none who have hit a home run — even Redfin has pivoted away from discounting and unbundling). The idea is the 6% commission previously paid for the huge bundle of services we listed above, and yet “researching available inventory” might only be worth $250 to us while “negotiating the price” might be worth $10,000. Can we create an a la carte menu of broker services and allow the consumer to pick and choose? Presumably the unbundling also assigns a fair wage to the broker and eliminates the adverse selection component where brokers are only paid by the one customer who transacts and not by all the flakey customers who waste time without buying.

Some counterarguments for why that hasn’t worked is that a skilled broker is able to synergize all elements of the bundle to gather the best possible experience. For example, because the broker took you on all the open house tours, that same broker knows to update your search, or knows what levers to use during the negotiation. Or, for the seller, because the broker is getting paid the commission, they care more about exhausting all channels of marketing and more diligently follow up with any potential buyers that visited (in the best cases they mine their own rolodex for potential buyers).

I’ll leave with one final cool counterargument against the unbundling approach. Lets assign a fair hourly rate to real estate agents, say $25 an hour. What if the sum total of all labor content value done by real estate agents is actually LOWER than the sum of all commissions collected? I argue in some markets that is true, such as the New York City rental market. Thousands of agents spend time and marketing dollars showing apartments to tens of thousands of customers. However, less than 10% of all online inquiries seem to result in a closed deal, and less than 25% of physical showings lead to a closed deal. It is possible that the average of all agents LOSE money, but because new agents enter the system all the time and below average agents quit the industry in disgust, then there are always a fresh batch of agents willing to work. If we believed the industry was a net-loss to agents but subsidized through recruiting and attrition, then any unbundling and a la carte approaches to broker services should be doomed to fail.

To build off of Dave’s point above, another value that accrues to the consumer through a broker is, arguably, an exhaustive awareness of the full supply in the market. While you would know FAR more about this than I would, any startup wishing to disintermediate the broker is (at least initially) going to be limited to showcasing the few options that have not signed contracts with large brokerages. The consumer wants and needs to know that she has access to all available options. Uber was able to overturn the taxi industry because it 1) provides undifferentiated supply (i.e. all driving experiences are arguably the same and fungible) and 2) found suppliers (drivers) who were not beholden to the Taxi Commission in the same way that building management/developers are beholden to brokerage firms. In short, do you think this disintermediation is possible without a sea change in the industry that allows for the full breadth and variety of residential supply to be available to the consumer online?

I agree that exhaustive inventory awareness is crucial, similar to how Li & Fung implied to customers that they had already done a comprehensive search of all possible suppliers, built the relationships necessary, and documented their capabilities. To maximize initial inventory, almost every site needs to partner with existing brokerages in order to bootstrap their supply. Without the supply, the severe network effect of a real estate marketplace nearly ensures failure.

Fortunately for all the companies in the space, real estate is notorious for low-cost multi-homing. Just as customers and drivers can choose to simultaneously appear on Uber, Lyft, and Sidecar; real estate suppliers can advertise on RentHop, but also a huge basket of competitors. As you mention, the network effect is even stronger, because unlike ride-sharing where each customer and driver is largely interchangeable, each parcel of real estate is unique.

The interesting implication is, when a large brokerage firm is advertising initially on an online website, who should pay who? The real estate firm argues that they are adding value to the site but sharing their inventory, therefore the Zillows of the world should pay for the data. On the other hand, the website operator argues they are spending vast amounts of marketing to ensure more leads, traffic, and business to the brokers, therefore the suppliers should pay to exist on the site. The answer is, it depends on the market dynamics, and more fragmented supplier markets are more likely to show the suppliers paying.

One last parting thought. Are all of the startups in this space initially agreeing to work with brokers in order to overcome the network effect problems, only to be secretly plotting a great back-door attack on the brokers? Once they are big enough to source supply and demand directly without the air of brokerage firms, is that the moment to pivot away into a pure distintermediation model? Zillow is the closest to achieving this goal, but with each earnings quarter, they announce even deeper partnerships and monetization models that include promoting the brokers and insist on the benefits of working with skilled agents.

Interesting read Lee. I’m of the opinion that the power of middlemen in these kinds of markets is eventually going to be hollowed out. Their resilience is admirable in the face of how much effort has been made to erode their utility, but nevertheless, eventually they’ll go the way of other broker types.

I think the most likely parallel here is in insurance brokerage, an industry that shares similarities with real estate (high stable margins for brokers, information asymmetry, long term purchase), but has been significantly disrupted by the ability of a consumer to online comparison shop, gather information themselves, and make a direct purchasing decision. The IIABA Marketshare cites digitization and direct to consumer sales multiple times as a huge risk to insurance brokerages and they’re seeing the market share of brokers erode steadily over the past decade.

There are two key differences that make real estate a bit harder to disintermediate than insurance. First, each home is a unique parcel of living space with infinitely many reasons a buyer might prefer home A over home B. Secondly, it’s usually considered essential to visit the new home prior to buying or signing a lease.

Health insurance, for example, has MANY finite parameters and options, but is still a largely quantifiable process of analyzing coverage, deductibles, and out-of-pocket limits. I applaud the Affordable Care Act for creating the bronze to platinum rating system, and hopefully someday market pressures completely commoditize plans into the “metal level” without concern for the underlying insurance company or network (the greatest difficulty would be the less quantifiable issue of whether enough of your preferred doctors are in-network).

To my knowledge, there is no concept of needing to physically visit or meet anyone prior to making an insurance decision, and in fact the human broker seems almost superfluous once all the insurance providers integrate with platforms like Zenefits or Gusto (which handles the administration, claims, and HR side of dealing with the insurance company).

Very interesting. The only option I can think of, that might have not been tried, is to outsource the broker function to someone living in an area with a lower cost of living. That way there is still a human involved to influence buyers emotionally but costs could drop significantly. Basically, a call center in India could try and achieve the broker functions, since they don’t actually need to be there in person to guide the buyer, and they could speak with potential buyers over video. From the customer side, you would call the call center and explain your needs and get matched with a real person who you will then Skype with. The client will remain with that service professional, conversing over video until a sale is made.

I have always liked the idea of utilizing comparative advantage and price discrimination schemes to lower overall costs of broker services. To extend your idea further, why not hold a mini-auction among a marketplace of brokers the moment a buyer is interested in a property? For example, you found an apartment online and 6 different real estate agents claim to be experts in that neighborhood. Could you hold a reverse auction, where the agents bid on the commission they will charge you if you ultimately buy? That way the agent who lives across town might bid a normal commission but the agent who lives upstairs in the same building will only require one third of the commission?

So far a lot of the reverse-search, discount-model, or auction based systems haven’t worked well. Foxtons famously tried to expand to New York City using a discount model and failed spectacularly. ZipRealty IPO’ed back during the first dot-com era but has fallen to a very niche player at best. The failure of any discounting model gives more supporting evidence to the theory that there is extreme variability in broker skill. Maybe finding a home is high-stakes enough that no one wants a discount broker? Alternatively, maybe it’s a matter of survivor bias. Maybe lots of people try using the discount brokers, but they ultimately don’t transact, hence the seemingly small impact these models have on the market.

As someone who used a broker to find my apartment in Cambridge, I am begrudgingly sympathetic to the role that brokers play. At the time I was looking for an apartment, I lived in Washington, DC and was traveling overseas 1-2 times per month. As painful as it was to fork over the broker fee, I simply needed to hire a person to help me manage the process. Among the functions you list above, my broker was most helpful in: aggregating listings, spotting good deals that matched my personal preferences, adjusting search parameters based on my reactions, and dealing with the landlord. Nevertheless, I might have been more reluctant to hire a broker if I lived in Boston and was just moving locally. Out of curiosity, how many people that hire brokers are moving within a city versus between two cities? I imagine that there will always be a market for rental brokers for people moving between two cities.

You are correct that there is a huge distinction between a relocating client and a current resident of the city. Traditionally rental brokers love relocating clients. They appreciate the neighborhood expertise more, they often have a higher budget thanks (possibly with the employer covering broker costs), and most importantly, they actually have a set deadline for moving and finding a new home. Current residents almost always have a lower conversion rate because they can simply stay and renew whatever arrangements they already have.

The emphasis on relocating clients highlights one of the reasons cracking the chicken and egg problem, aka bootstrapping the networking effect, is so difficult. By definition, a relocating client only needs to use an online service once, and never again until the next city relocation. That means for a startup, product diffusion by word-of-mouth or brand equity is very slow, unlike say Airbnb and Uber, which are services that draw repeat customers multiple times a year. Real estate startups rely heavily on paid media, earned media, SEO, and partnerships to drive new traffic, and sadly many of those are zero-sum games. Only one website can be at the very top of the most relevant Google searches.

Great post, Lee. I agree that technology can disintermediate broker functions easily in some areas and less easily in others. I also agree with Max that there is a hollowing out of the middleman’s power in real estate, but there are limits to that effect. In the case of real estate transactions, governments and regulators are incentivized to protect the industry (and real estate agents’ jobs) by creating and maintaining licensing schemes that act as obstacles. Government may be slow to react to technology, but it protects real estate agents more than it did other professions disintermediated by technology, such as travel agents for personal travel.

As you know well, human brokers have also remained relevant in come cases by sharing their fees with other middlemen and even customers, lowering the cost of the broker in the digital age to something that housing seekers consider more reasonable. I think this is especially powerful when financial institutions create their own broker referral programs for members, which is on the rise. Dave wrote a post about USAA, which has a “MoversAdvantage” program that gives home buyers and sellers a cut of the real estate agent’s fee (basically the referral fee, most of which USAA passes on to its members). https://www.usaa.com/inet/pages/bank_m?akredirect=true

Regulation in the real estate industry has had a huge impact, both good and bad, in this country. We often take this for granted, but the Civil Rights Act and Fair Housing Acts have been essential to allowing equal opportunities in housing (short story, landlords and sellers previously practiced outright and flagrant discrimination; now it is at best subtle or circumstantial). Other laws exist to protect consumers from scams.

So while not all real estate regulation is bad, I agree there should be more requirements to give consumers access to crucial inventory and transaction data. There was a famous lawsuit in the early 2000s between software vendor MLX and the Real Estate Board of New York (every major brokerage firm and competing vendor in town was ultimately named as a defendant), disputing the anti-competitive practices of the industry group restricting which vendors were allowed to access, join, and participate in the intra-brokerage data sharing procedure. After years of bitter fighting, they finally reached a cash settlement and given access, but by then MLX had lost almost all of their clients and were soon forced to shutter operations. MLX was founded by Lala Wang (HBS ’78), who is a RentHop investor and adviser.

http://www.webcommentary.com/php/ShowArticle.php?id=gaynorm&date=070905

It is admirable how resilient the real estate broker market has been to online disruption. I would argue that nearly all of the “possible to automate” and “difficult to automate” functions can indeed be replaced for digital technology. I suspect that lower to medium end rentals in large cities like New York City will be the first to transition to an online platform, and that high end, multimillion dollar home sales will always require the human touch of a physical broker. I believe that trust is the primary function that real estate brokers serve, and it is only a matter of time that we begin to trust the technology that bring buyer and sellers together. Lower to medium end rentals in NYC inherently require less trust because they are less meaningful transactions because renters typically don’t rent the same apartment in NYC for a very longer period of time. The broker market has already gone by the wayside for short term rentals because of AirBnb or VRBO, and I anticipate that this trend will continue to creep into the longer term rental market as well.

It sounds like the players so far have primarily tried to compete symmetrically with brokers, with a strategy (at least initially) of totally replacing the broker.

Strategically, it feels like there are 2 alternatives.

1) Automate some tasks so that brokers become more productive. This should lead to fewer total brokers needed (per some number of houses), and those brokers would make more money. Then long term, I would expect competition to drive down the revenues brokers can capture, decreasing the cost to sellers, and shifting some of that value to software companies.

2) Find markets where the benefits are preferred, while the drawbacks are immaterial. For instance, rentals may be a better market than houses for sale, since it involves less of an investment (per Dave’s point). You could also start by targeting first-time renters who would otherwise advertise on craigslist. In addition to offering a more targeted platform (it also wouldn’t be hard to make it look better), you could also offer services such as standard rental contracts, and even a payments system that automatically deals with delinquent payments (and documents these in case things get bad).

Have you seen anyone attempting to pursue either of these strategies?

Thanks for the post Lee. I think that it is possible that the business has deteriorated worse than the standard 6% that you listed above. My first thought is that it’s possible that the data doesn’t include the full blended rate – i.e. how many people are not participating in the market that are not trackable which would reduce the percentage fee. The other thing that I think may be happening is that while topline is relatively steady, sellers have to work far harder from a cost perspective to add value and so are getting squeezed in terms of profitability. This is summarized better by this writer (https://www.washingtonpost.com/realestate/commissions-of-6-percent-for-home-sales-are-the-norm-but-that-is-changing/2016/04/13/91bb758c-fb55-11e5-886f-a037dba38301_story.html)

“Zillow wasn’t as big and powerful in the past, which meant that the MLS (multiple listing service) that served Realtors was their ace in the hole. That barrier is gone. Recognizing the growing threats, the real estate industry is racing to automate and add technology. In every industry where this happens, margins contract. This industry is no exception, and commissions are dropping dramatically and quickly.”

As already mentioned, interesting read and . I once was a licensed real estate agent and have thought about the differences between many of the points you mention early on as easy to automate vs. those that you listed as difficult to automate.

While it seems there are a lot of tools out there to help agencies market their listings and manage the back office (http://www.capterra.com/real-estate-agency-software), I wonder whether RentHop could provide value – added tools to help automate some of the “easy to automate” tasks that using up agents’ time? For example, in your description, it seems like a lot of the set up in a transaction (ie. collecting documentation, the initial matching of buyer preferences and budget with availability as a simple task to automate) is easier to automate than the iteration that takes place in the showing setting. Perhaps reducing this set up time would free up agents to give more showings.

I find it interesting that even in a developed economy like the US, there is enough on the table that brokers bring. While your article touches on the possibility of automation, I think there has to be a far greater emphasis on the “soft information” that brokers have. In emerging economies (like India), the broker has a wealth of local knowledge. Plus they usually add the most important layer – trust. Trust is very difficult to build online. You indirectly mention this by mentioning the things that one cant automate. In India, we saw 100s of millions of dollars go down the drain as US investors backed large online “brokerless” models in 2014 and 2015. However come 2016, the focus has shifted to online startups which assist brokers – has a similar trend been observed at mass scale in the US as well?

https://inc42.com/flash-feed/housing-layoff-600-employees/

http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/property-/-cstruction/jll-partners-brokers-network-platform-broex-to-sell-homes/articleshow/51550354.cms

Well met, Lee. Your post made me recall a conversation I had with a gentleman in New York a couple years back about the real estate market – specifically regarding the role of brokers and the value (or lack thereof) that they provide. At the time, I felt strongly (and still do today) about technology one day disintermediating the real estate broker, but this gentleman countered by saying the process of buying or selling a home is analogous to one going to see the doctor. Nowadays, patients can have as much access to information as doctors have, but at the end of the day, the patient will still go to visit the doctor because the doctor is the “expert.” Leaving aside the absurdity of that comparison (e.g. virtually anybody can become a licensed real estate broker, whereas becoming a doctor requires years of education and training), he does have a point. Trading stocks and booking flights have been commoditized and no longer require human agents, but real estate is different because finding a home is, as you said in your post, “is as much an emotional decision as it is quantitative.” Since none of the others who commented have posted about this yet, I’d be curious to hear your thoughts about what you think of this company called Trelora. They are a full-service brokerage that only charges its clients a flat fee ($2500) as opposed to the 5-6% of the purchase price. Unlike traditional brokerages, the firm pays its agents a regular salary and benefits as opposed to the commission-only compensation split of traditional brokerages. Trelora is currently limited to the Denver market, but seem to be gaining some traction and they have been getting rave reviews.

http://www.trelora.com/