Where in the world will our wine come from?

Climate change is threatening to disrupt the global wine industry supply map. How will wine producers evolve?

Con vino y esperanza todo es posible (with wine and hope, anything is possible). The Spanish proverb sums up the world’s love affair with wine – an industry forecasted to reach more than 30 billion liters by 2020 (TechNavio, 2016). However, global warming looms large, threatening to redraw the global supply map. Optimists have pointed out that the exciting possibilities of wine from northern regions (who’s ready for Scandinavian wine!), but for grape varieties central to regional industry and culture, changing temperatures could mean entire wine growing regions becoming obsolete.

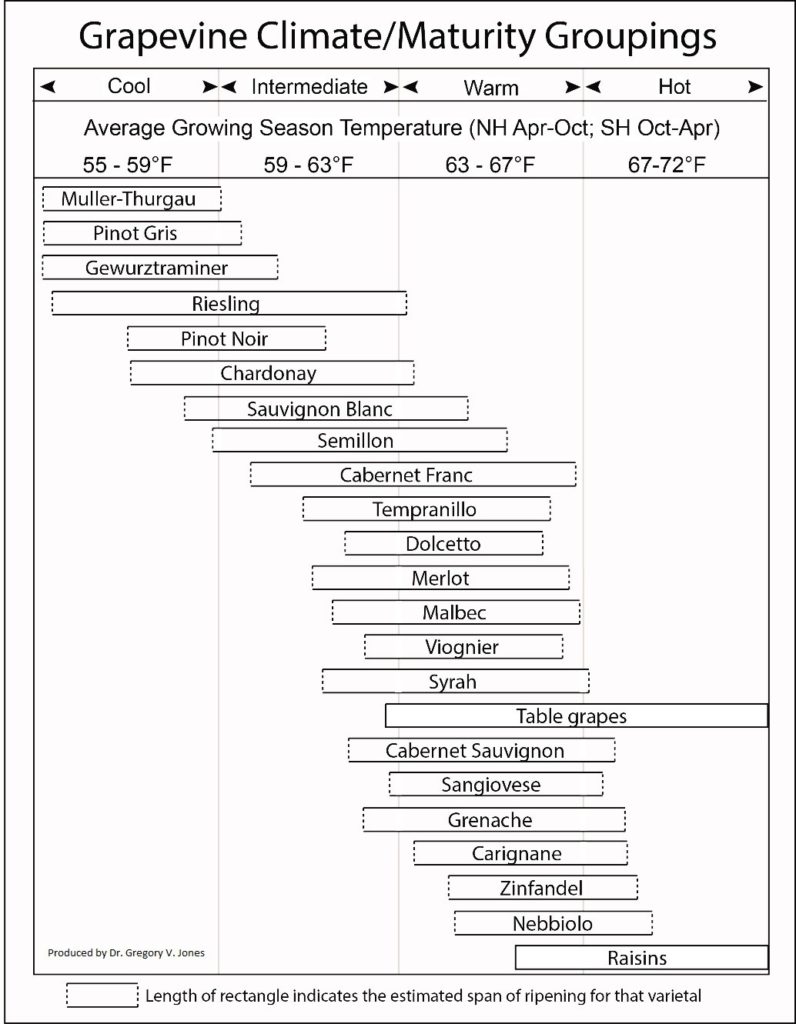

Average temperature and growing season length directly influence grape ripening and fruit quality. Growing seasons average approximately 170-190 days, and the specificity in climate and geographic traits required (exhibit 1) means that wine grapes are more susceptible to climate variability and long-term climate change than other commodities. Further, climate can dictate taste; cool climate grapes produce wines with lower alcohol and a lighter body, while hotter climates tend to produce bolder wines with higher alcohol. (Jones, 2017). The UN Panel on Climate Change projects a 2C warming scenario, while researchers at the World Bank have modeled for a 4C increase – changes that will have a drastic impact on types of grapes grown worldwide (Gledhill, Hamza-Goodacre and Low, 2013)

Nederburg wine company is located in South Africa’s Western Cape, a renowned growing region bordering the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Nederburg has produced wines for over 225 years and is recognized as one of the top South African Wine producers.

Company actions – product innovation upstream

To combat future temperature increases, Nederburg growers have introduced grape varieties new to Western Cape region, including the hybrid Chambourcin grape. Hybrids are mixes between different grape species (i.e. European and American species), and have the potential to be more robust – one of the most successful hybrids has been the Vidal Blanc, a grape which is resistant to cold weather and is used in Canada to make ice wine. (Dami, Ennahli and Scurlock, 2013). Chambourcin is a well-known hybrid in the U.S. and Australia, for its ability to withstand extreme weather conditions – important for dealing with extreme variance in the medium to long term. Nederburg is running tests with these unusual grape varieties, experimenting and planning for future vintages. These grapes are run in smaller batches concurrently with the traditional grape crops, to observe their comparative yield and ripening time. (Augustyn, 2017)

In the short term, Nederburg’s viticulturist, Bennie Liebenberg, highlighted that the winery has been experimenting with more traditional Mediterranean grapes suited to warming temperatures for more than a decade. Both Tempranillo and Graciano (exhibit 1) were planted in 2004, and Nederburg previously introduced Italian varietals such as Sangiovese, Nebbiolo and Barbera. From these, Nederburg developed an Italian blend that was the first of its kind to be launched in the Western Cape. (wine.co.za, 2017).

Nederburg’s long term change in grape choice impacts Nederburg’s entire business model given demand depends on carefully curated wine tastes. Nederburg has had to update their sales strategy and attract different end consumers and distributors for their updated products.

Potential improvements – rotating supply schedules/mechanical upgrades

Another potential solution to deal with projected temperature increases is altering the supply chain timing – rotating the growing and picking season. Some competitors in other Southern hemisphere countries, such as in Chile, are picking their grapes a full month earlier than traditional seasons. The length of the production time is adapted to get the right quality. Vriesenhof Vineyards, a local competitor, has also shifted its production schedule: “usual to start the harvest around February 5. In recent times, harvesting is starting earlier…in 2007 the harvest began on January 23; in 2010, on January 21; and in 2015, on January 7”. (Coetzee and Adelsheim, 2016)

Finally, there are mechanical improvements growers can make to their process to mitigate rising temperatures and improve productive yield. Irrigation allows producers to manage rainfall amounts during dryer seasons, while canopy management – structuring the the vines to a greater height then taking them horizontally to ensure that the grapes are shaded – can keep the temperature of the grape bunches at ~25C even in extremely hot weather. (Coetzee and Adelsheim, 2016)

“At the end of the day, people are still going to want to grow wine in Bordeaux in the future…So, we wanted to get more information about what is happening here…Winemakers do not need to be complete slaves to what the environment does.” (Bland, 2016)

Questions

As climate change affects wine production – should wineries alter their products (South African wineries producing “Italian” reds), or pour more money and resources into producing regional classics?

Will increased variance (higher likelihood of crop loss) and average temperatures (need for process innovation) drive an exit of small-scale wineries and consolidation into national/international growers? How should Nederburg plan for this?

(Word count: 798)

Bibliography

Augustyn, W. (2017). Nederburg: Carrying on into the future – Wineland Magazine. [online] Wineland Magazine. Available at: http://www.wineland.co.za/nederburg-carrying-future/ [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

Bland, A. (2013). With Warming Climes, How Long Will A Bordeaux Be A Bordeaux?. [online] NPR.org. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/05/06/181684846/with-warming-climes-how-long-will-a-bordeaux-be-a-bordeaux [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

Bland, A. (2016). An Upside To Climate Change? Better French Wine. [online] NPR.org. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/03/21/470872883/an-upside-to-climate-change-better-french-wine [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

Coetzee, J. and Adelsheim, D. (2016). Climate Change: Field Reports from Leading Winemakers. Journal of Wine Economics, Volume 11, pp.5–47.

Dami, I., Ennahli, S. and Scurlock, D. (2013). A Five-year Study on the Effect of Cluster Thinning and Harvest Date on Yield, Fruit Composition, and Cold-hardiness of ‘Vidal Blanc’ (Vitis spp.) for Ice Wine Production. HortScience.

Gledhill, R., Hamza-Goodacre, D. and Low, L. (2013). Business-not-asusual: Tackling the impact of climate change on supply chain risk. Resilience: A journal of strategy and risk.

Jones, G. (2017). Climate, Grapes, and Wine. [online] GuildSomm. Available at: https://www.guildsomm.com/public_content/features/features/b/gregory_jones/posts/climate-grapes-and-wine?CommentId=8e6b0cd5-1f30-4922-ad27-538cfe8704cf [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

Lee, H. et al (2013). Climate change, wine, and conservation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

Perrone, T. (2017). How climate change could transform the world’s wine map – LifeGate. [online] LifeGate. Available at: http://www.lifegate.com/people/news/climate-change-wine-production [Accessed 16 Nov. 2017].

TechNavio (2016). Global Wine Market 2016-2020.

Vink, N., Deloire, A., Bonnardot, V. and Ewert, J. (2009). Climate change and the future of South Africa’s wine industry. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management.

wine.co.za. (2017). Nederburg plants new vines in old soil to commemorate its history. [online] Available at: http://www.wine.co.za/news/news.aspx?NEWSID=29893.

It’s quite interesting to read how the different effects of climate change may benefit wine grapes in some ways (overall warmer temperatures, new regions become feasible for growing vines) but harm them in other ways (drought, severe weather). Evidently it is still unclear whether climate change will be a net benefit or detriment to the wine industry. It seems the main risk is an increase in variability in crop quality and yield, as well as flavor/taste – i.e. concept of terroir. Something wine producers will have to grapple with is a bit of an existential thought exercise – is a glass of merlot wine still considered merlot if the climate change-impacted grape tastes very different from the traditional Merlot grape?

Interesting. I guess it really depends on the grape varieties. Researchers in traditional regions like Bordeaux are already exploring cultivars better adapted to varying climate conditions and diseases. French agriculture-research institutions are studying Plot 52, a parcel planted with 52 different grape varieties, including some from Portugal, Greece and Italy. The goal is to identify varieties better suited to hotter climates.

I guess site selection also matters. Grape growers may need to plant their vineyards at higher latitudes or higher elevations to capture cooler climate conditions. In Germany’s Mosel Valley, they’re doing just that. They have moved plantings higher on the region’s hillsides, closer to the crest where the wind provides a cooling effect.

Despite the uniqueness of Scandinavian wine (would it be blue?), I do not think that France and California need to be applying for visas any time soon. The cachet of Napa and Bordeaux will continue to drive consumer preferences. Even temperate Napa has wide swings in average temperatures by month (average high of 55 in January and 80 in July, per U.S. Climate Data), allowing wineries to offset spikes in temperatures by shifting crop cycles to earlier or later in the year.

As temperatures become more volatile, I do believe that the industry will consolidate to offset the risks of operating a single vineyard and producing a failed vintage. Across several sectors in the United States, industries are consolidating. Airlines, hospital systems, consumer packaged goods, and telecommunications are less competitive than in the past. In recent years, we have already started to see several large acquisitions in wine, such as the acquisition of Prisoner Wine by Constellation Brands for $285 million in 2016. The trend could accelerate quickly considering that several Northern California wineries were founded in the age of the “Judgment of Paris” in the 1970s. The founders are prime for retirement.

Warming temperatures should not be brushed aside. Yet, I also question the threat of consolidation, rising prices, and a reduction in variety. Large wine corporations with deep pockets for marketing dollars will also begin to take on the heavily advertised spirits industry. Diageo and its peers should be wary.

Could there also be a benefit for existing wineries with respect to climate change? I imagine that as it becomes increasingly more difficult to produce classic varieties there will also be increasingly more demand for the remaining options. As we can see with many luxury goods, instilling a sense of scarcity and exclusivity can be a very compelling marketing tactic that allows companies to not only ensure that their product is sold but also to command a significantly higher price point. Wine connoisseurs already take great pride in discovering and owning rare/unique vintages, and a restricted supply will likely make the competition even more intense. In this scenario, wineries will have to balance the tradeoff between quantity and price in order to ensure they are able to sustain their businesses.

Important problem to solve for any wine enthusiast! Climate change will create new questions / challenges for wine makers all over the world. At the extremes, I believe some of the warmest regions will not make (the same) wines 30 years from now vs. today. In some cases, technology or other solutions can help, but at the end of the day, it’s hard to grow wine in a desert-like environment (assuming that for some regions temperatures would go up by that much).

Looking at the current footprint of the wine making industry, I believe there is overall an opportunity as more regions will become great places to make wines (e.g., parts of the US, Europe). The core regions suffering from extreme heat, rising sea levels, and other climate change effects are around the equator in Latin-America (Chilean and Argentinian wine is typically made well above sea level), Africa, and Asia, most of which are not wine regions today.

Finally, as climate gradually changes, so will our preferences. This will create room / pressure for innovation in the industry, hence to answer the authors question: No, the wines and grapes will not be the same, nor have they been over the past 200 years.

From over 200gr of sugar in champagne 200 years ago, vs. 3-6gr today, relatively demise of port, rise of (high quality) rose wines, rise of Californian Cabernet and Oregon Pinot as well as Australian Shiraz… All of these innovations, whether grape, location, or style, have accommodated changing preferences. I believe that great winemakers will continue to do so for the next 200 years.

Worried Sommelier, you have definitely worried this wine lover! Hybrid grape varieties are an interesting solution to this dire situation. Are the hybrids you mentioned selling as well as the wines Nederburg traditionally sells? Although they may be able to replace some of their crops with these varieties, I would be nervous about the success of these new wines. Particularly considering the smaller batch size and the slow evolution of the carefully curated wine tastes that you mentioned. That said, I’m not wineries can afford to keep investing in resources to produce regional classics as it seems those resources will not be able to keep up with the pace and long term repercussions of climate change.

Another worried wine lover here! 🙂

Very interesting read…I agree with Noemie Renaerts’s last point: I believe climate change will drive innovation in the wine industry. Natural threats often represent opportunities – examples I am thinking about: use of botrytis to develop new flavor profiles in wine (and continuous innovations in that space, e.g. Verglas wine by Stoneboat Vineyards), or wine grafting to battle phylloxera. I am curious to see what solutions winemakers will develop.

Very interesting. I wonder how much of the technology and innovation – in process, location, type of grape, will eventually dictate a change in the brand value of certain wines. To Cindy’s point – will people still want a merlot if it tastes nothing as a merlot? On the other hand, how many “day-to-day” consumers know exactly how a merlot should taste like? As Noemie pointed out, I believe consumers will adjust their tastes, mind and expectations to both accept the taste evolution of “old wines” and more openly embrace technology and climate change “enabled” new wines. The question for me remains – how and when should wine producers, such as Nederburg, start to evolve with the climate and consumer changes?

Interesting article! While large scale producers may have trouble with the climate change occurring, one can also envision a world in which wineries grow smaller and smaller rather than consolidate. One way of controlling climate, which would likely be too expensive for a very large plot of land, would be to artificially control it within a regulated indoor environment. Wineries could grow smaller to fit into such spaces, and we may see highly controlled, finely tuned micro-wineries cooking up unique reds and whites similar to what we see with microbrews!

Indeed a tricky problem for the wine producers. I see three outcomes for this problem from a supply chain point of view: 1. Place, 2. Raw material and 3. Process. Starting with place, the first solution for wine producers would be to slowly start shifting / adding production in new areas with better climate suitable for producing wine of a particular grape. Second (for raw material), the wine producers could stay at their current locations but over time introduce grapes more suitable for the changing climate in their current region. Third (for process), the wine producers could stay in their current locations and use their current grapes, but introduce processes / machines that better adjust the grapes and the soil for the changing climate.

Nederburg must be both adaptable and resilient in order to address the impacts of climate change on its grape varieties. As a recognized, long-time wine producer in South Africa, it should not completely abandon the production of core offerings, but should gradually set the stage for its future characterized by a wider range of offerings. The introduction of grape varieties that are more resistant to cold weather conditions is an effective starting point, but additional actions should be taken. Consumers trust curated wine lists and informed sommeliers to “dictate” their preferences. With this in mind, Nederburg should focus on adjusting its sales strategy and partnerships to not only target distributors and end consumers, but also sommeliers, restauranteurs, and wine critics. These individuals are influential in driving demand for different grape varieties and can drive demand for Nederburg’s new blends over time.

Additionally, “reducing emissions has already become a mandate for many in the wine community.”[1] Nederburg could consider investing in climate-related innovations so as to reduce its carbon footprint and play its part in combatting climate change. For instance, Miguel Torres, President of Bodegas Torres of Spain and Chile, has invested considerably in such innovations, including CO2-eating algae and converting CO2 into plant fertilizer.[1]

[1] http://www.winespectator.com/webfeature/show/id/Vinexpo-Bordeaux-Climate-Change-Wine-Conference-Fire-and-Rain

Interesting piece – lots of considerations here. Few to add to the discussion:

1) Innovation will remain key in the space – do we get to a place where, to combat the effect of global warming, more resource/infrastructural measures (climate control, for example) need to be put in place to produce wines according to traditional palates? This will drive the price to produce these wines much higher, perhaps generating a new (and potentially not “green”) class of high end wine

2) Red blends have certainly lost their pejorative connotation in the mind of consumers… in some cases, consumers associate blends with a higher degree of craftsmanship and individuality (see: Japanese whiskey vs single malts for a comparison). This may offset some of the necessity of single-grape varietals as perception and taste shifts.

3) To your second question, I see this less as the demise of the small-scale winery but the demise of the ability to bootstrap given risk – we’d probably see a lot more incubator-like investment by specialists with a large portfolio with some sort of profit share across regions – retaining quality but also offsetting risk (co-op like behavior). See what the Japanese have done with the luxury high-end coffee market in Jamaica.

Really interesting, thanks for sharing! My first thought upon reading this article is whether, in addition to changing the location of growth and the type of grape, there have been advances in technology that make it easier to protect crops from the impact of climate change. At a fundamental level, wine production is really an agricultural process, and it would seem that the broader agricultural/food industry is facing similar problems that wine producers are facing. As such, I’d imagine that there is currently significant investment from large food companies in technologies and processes to facilitate the production of good crops amidst a changing climate. One worry I have around wine that other agricultural companies may not face is that consumers may be reluctant to show the same “respect” for wine that they view as being produced in an “artificial” or more digitized/technologically advanced way. Part of the allure of wine is the craft of production and I worry that the production changes required by climate change will ultimately hurt the brand of wine to the end consumer. As wine producers navigate this challenge, they will likely be looking to optimize around not just protecting their crop and production process, but also around managing the appearance of any changes to process as understood by the consumer.

I also agree with Noemie and Michelle’s points: if “necessity” is the mother of invention, “adversity” may be the father of innovation. That said, I am curious to see how these environmental realities will jibe with the more “emotional” nature of the wine industry. In a world where the value of a French Bordeaux stems from the soil its grown on, how will environmental change impact brand perception and pricing? This calls into question a very fundamental concern — what makes wine, “wine.” Its soil and heritage, or its flavor?

I completely agree with Ramis Junnarkov and had a similar thought as I was reading the article. Wine consumption is such an emotional experience, it is unclear to me whether companies will be able to make the adjustments required to combat climate change without entirely alienating their customer bases. For example, you mention the hybrid Chambourcin grape as a potential solution, but I can’t help but wonder if the idea of a hybrid grape tarnishes the brand equity of Nederburg. For true wine enthusiasts, I imagine many of the innovations or solutions proposed above will be perceived as diminishing the integrity of the wine, so companies must be thoughtful in how they a) execute and then b) communicate climate-change initiatives.

This is a particularly interesting read for me; I recently wrote a similar note about coffee. I see two major differences with coffee: (i) grapes are a much more resilient crop; (ii) wine producers in France, Italy, South Africa, Australia, or California are typically sophisticated players with access to capital (relative to smallholder coffee farmers in Uganda, or Guatemala).

I see three different types of responses: (i) letting scarcity happen and adjusting prices (this could work for higher end wines); (ii) using technology to fight the effect of climate change; (iii) growing wine in new regions.

It’s interesting to think about whether current wineries will need to 1) change their production schedule based on global warming or 2) change their product. In the case of wine, I do believe that wine needs to be exposed to certain temperatures to properly ripen, and that changing in production schedule is likely the first move to adjust to changing temperatures. I wonder if the same grape will respond similarly to weather patterns (i.e., going from cold to warm), even though the timing may be 1-3 months from usual. If so, I do think that we can keep the products in the same regions for the long run.

It’s an even more interesting point to consider that wineries may need to adjust the products themselves, where Bordeaux will need to be grown in areas outside of France that will now have similar climate to historical France. I think this will be hard to sell to the customer, who has long associated the quality and type of wine with the source location. As we learned in the Chateau Margaux case for Marketing, a lot of intrinsic value is placed in exactly what plot of land the grapes are from. Wineries face a difficult hurdle to educate customers on the impact of climate change to their wines, and will need to manage a resistant expectation that wines are as good as their region.

Very interesting and entertaining article. I believe that the answer to your questions will also depend on the demand for both types of wine. If there is a reasonable demand for wine produced with mediterranean grapes, small-scale wineries will probably produce such altered products that require less investment in mechanical improvements. Larger producers will adapt their production mechanism to continue producing their traditional wine (of course, depending on the demand and production cost for such wines). I honestly even see the production of altered mediterranean wine in South Africa as an opportunity. Since wine is unique (soil, topography, humidity, etc.) , altered products can end-up being significantly better than their original ones (optimistic assumption) and present new market opportunities.

I imagine that this will be an area where different strategies make sense for different consumers. For the classic french wines I really can’t imagine that consumers will pay the premium prices if the growing methods or grapes themselves are altered too much. On the other side of the coin I imagine that you can continue to produce Franzia with the most economic means available, whatever those end up being. I find the idea of hybrid grapes pretty intriguing, and even wonder if there may be some genes from plants that are used to even more arid conditions (e.g. cactus) that could be put to use in helping grapes grow in hotter climates.

Agriculture in general is marked by changes in the crop – genetically modifying them through selected planting. For example, corn 10,000 years ago was barely a sliver of tiny kernels. The more hearty and larger kernel crops would be identified and replanted to eventually, through many thousands of years, create the full cobs of corn we purchase today. I suspect with more advanced techniques for identifying temperature-resilient strains there would be plenty of room for growers to selectively plant only those strains hearty enough to withstand increasing temperatures. At the same time, the consumer might have to change their own preferences for wine – given the rising demand for wine, I don’t see this as a big issue.

With 20 preceding comments it is hard to say something new. But to my mind, one aspect is missing in the discussion. How will climate change affect the availability of water in wine-growing regions? For wine production, 872 gallons of water are needed in the production process of one wine gallon (1) The availability/reliable availability of water resources is thus a decisive factor. Climate change could desiccate whole regions.

[1] Boehrer, Katherine. Huffpost. April 13, 2015. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/10/13/food-water-footprint_n_5952862.html (accessed 12 01, 2017).

Very interesting read, especially because it is about a product that we all can relate to 🙂

There is usually a lot of negativity and concern associated with Climate Change. In a very refreshing way, this writeup introduces opportunities and benefits associated with Climate Change. I am personally entirely on this side. With access to better technology in general, there will be ways to mitigate the negative effects of climate change as far as wine supply chain is concerned – negative effects such as variability, inconsistent quality and flavor. Hence we will always be left with a net positive effect of climate change in this case.

This was an interesting article and I never would have thought about the topic on my own. Over what period does the UN Panel and World Bank estimate the 2C and 4C respective increase in temperatures? Your solutions to the problem are definitely worth considering. Aside from the hybrid mixes, do you know if GMO grapes have been considered in the process? Have you looked into how the sourcing change in grapes or mechanical improvements could impact profitability?

Thanks for sharing this post! While I was reading through the article, I was trying to think through what technological advances are out there to be able to curb climate change’s impact and protect the grapes. Do you know of any? Climate adaptation and mitigation, until we are able to combat in big ways the root causes of climate change, are key to survival for both winery and agricultural industries. Thus, to answer your first questions, blending, in this sense, is a necessary step to continue to survive within this industry. I am not sure if they necessarily have a choice.