When HHS becomes iOS: Harnessing Open Innovation to Combat the US Opioid Crisis

Can same approach that delivered an open source operating system and the free encyclopedia help address the opioid crisis?

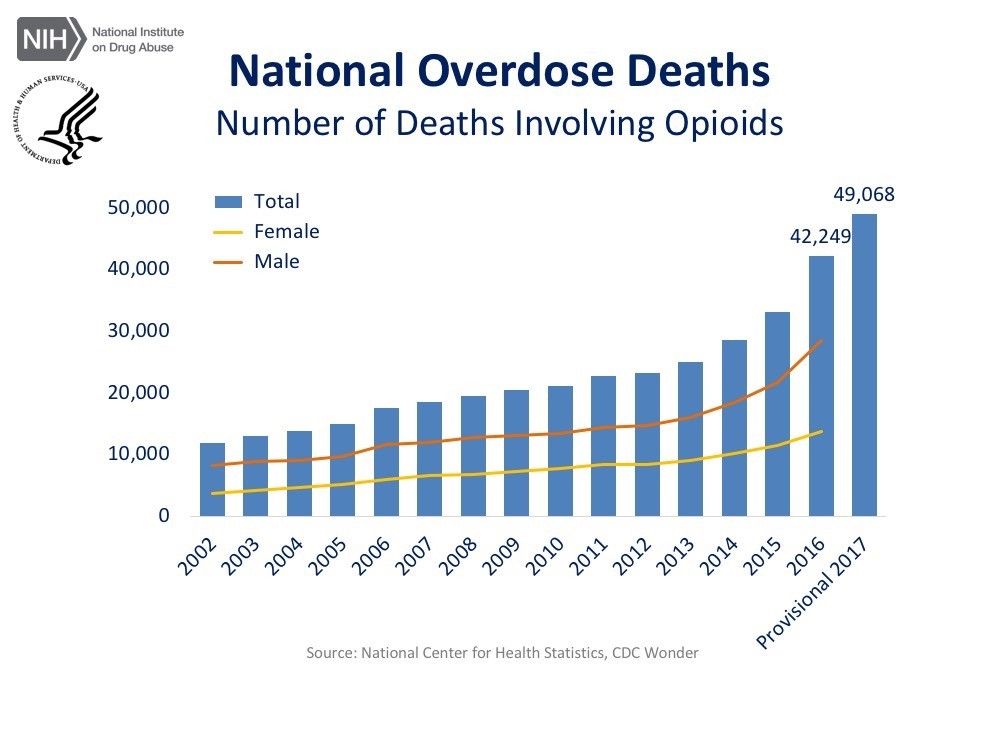

The US opioid epidemic has rapidly evolved into one of the most significant national health crises in recent history. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimates that opioid overdose contributed to over 49,000 deaths in 2017, a nearly 250% increase from 2010 (see figure 1)1. Positively, preliminary data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggest that opioid-related deaths have declined three percent from September 2017 to March 20182.

HHS: Open for Innovation

Despite the apparent slowing of opioid-related deaths, much work remains. In addition to the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (signed into law in October 2018)3 and an extensive list of private-sector partnerships to help deliver solutions to address the opioid crisis4, HHS has announced a five-point strategy to combat the crisis (see figure 2)5. Given the unique challenges of the opioid crisis – including flight to illicit drugs as prescriptions are curtailed and significant under-diagnosis and underreporting of opioid use – HHS is looking to open innovation to help address the challenges ahead6.

Fortunately for HHS, it is not the first organization to apply open innovation outside of Wikipedia, iOS, or Linux. Chesbrough and Crowther (2006) find that while open innovation has historically been reserved for high-technology industries, firms in other industries are increasingly – and successfully – employing such approaches to solve their own business challenges7. Further, HHS is not the first government agency to consider innovation tournaments: in 2010, President Obama launched Challenge.gov, a federal prize competition platform that awarded more than $150 million from 2010 to 20158. If open innovation works for non-high-technology businesses and the Obama White House, why not HHS?

Code-a-Thons: Exploit, Don’t Explore

In December 2017, HHS held its first Opioid Code-a-Thon. The event was structured as an innovation tournament, with 50 teams competing for a $10,000 prize in each of the three challenge tracks: treatment, usage, and prevention.9 Examples of winning submissions include Telesphora (treatment), which allows real-time tracking of opioid overdoses, and Visionist (prevention), which introduced “Take Back America,” a live-updating map of pharmacies where patients can return unused opioids10,11.

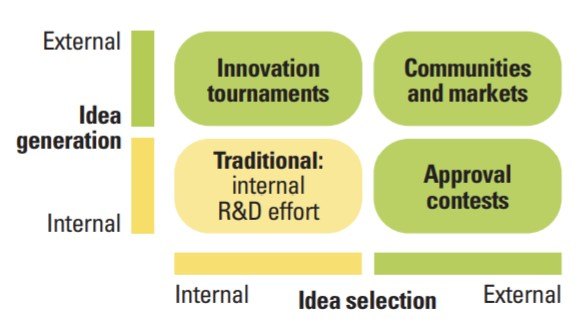

What was HHS hoping to accomplish with the Code-a-Thon? King and Lakhani (2013) provide a helpful matrix to evaluate innovation approaches (see figure 3). HHS’s Code-a-Thon falls into the “innovation tournament” category, comprising externally-generated ideas that are internally selected.12 This categorization provides valuable insight into HHS’s goals for its open innovation initiative: while HHS is eager to source ideas from external partners, it wants to select ideas that fit with its existing 5-point strategy.

Put differently, HHS used the 2017 Code-a-Thon to exploit resources to move incrementally along the innovation landscape in the short term. It remains to be seen whether HHS’s medium-term goals include more exploitation (i.e., more products like Telesphora and Take Back America), a shift to exploration (larger, more transformational jumps), or some combination of the two.

Increasing the Role of Open Innovation

In the short term, HHS’s decision to leverage innovation tournaments to solve specific problems will continue to generate valuable new ideas to address the opioid crisis. Depending on the efficacy of the initial Hack-a-Thon ideas, HHS should continue to pursue such exploitative innovation tournaments where applicable. Better data (see figure 2) appears to be a natural area where HHS could expand its innovation efforts, potentially incorporating novel data sets such as cell phone geolocation data.

In the medium term, however, HHS should reevaluate its approach. Brendan Saloner, a professor at John Hopkins’ Bloomberg School of Public Health, appropriately notes that “we’re not going to code our way out of this problem”13. Saloner’s assertion recalls King and Lakhani’s matrix: innovation tournaments will spur new ideas, but only ideas that align with a pre-determined approach to addressing the opioid crisis. To harness the true power of open innovation, HHS should endeavor to create a community where ideas are both contributed and selected by external parties. This approach will enable those closest to the crisis – first responders, nurses, physicians, and others – to act on those ideas that they know will drive the greatest change, creating the possibility of exploration on the innovation landscape instead of just exploitation. While HHS undoubtedly incorporates perspectives from these on-the-ground stakeholders today, creating an open innovation environment that encourages open collaboration between idea generators and idea selectors will maximize the value of open innovation to combat the opioid crisis.

Questions for Further Discussion

Should HHS transition open innovation to address the opioid crisis from innovation tournaments to an open community with external idea generation and idea selection? Why or why not?

How does the high-stakes nature of the opioid crisis change the role that open innovation plays in addressing this unique challenge?

(774 words)

Sources

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. “National Overdose Deaths—Number of Deaths Involving Opioid Drugs,” https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates, accessed November 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm, accessed November 2018.

- SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act, HR 6, 115th Cong. (October 24, 2018), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/6, accessed November 2028.

- The White House. “A Year of Historic Action to Combat the Opioid Crisis,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/year-historic-action-combat-opioid-crisis/, accessed November 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. “5-Point Strategy To Combat the Opioid Crisis,” https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/hhs-response/index.html, accessed November 2018.

- Sarun Charumilind, MD et al., “Why we need bolder action to combat the opioid epidemic,” McKinsey & Company, September 2018, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/why-we-need-bolder-action-to-combat-the-opioid-epidemic, accessed November 2018.

- Henry Chesbrough and Adrienne Kardon Crowther, “Beyond high tech: early adopters of open innovation in other industries,” R&D Management 36, 3 (2006): 229-236.

- The Obama White House. “Prizes and Challenges,” https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/administration/eop/sicp/initiatives/prizes-challenges, accessed November 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. “HHS Opioid Code-a-Thon,” https://www.hhs.gov/challenges/code-a-thon/index.html, accessed November 2018.

- https://telesphora.com/, accessed November 2018.

- Visionist, Inc. “Take Back America,” http://takeback.labs.visionistinc.com/, accessed November 2018.

- Andrew King and Karim R. Lakhani, “Using Open Innovation to Identify the Best Ideas,” MIT Sloan Management Review 55, No. 1 (Fall 2013): 41-48.

- Issie Lapowsky, “Tech Alone Can’t Solve the Opioid Crisis,” Wired, December 21, 2017, https://www.wired.com/story/opioid-crisis-hackathon-tech-health-care-funding/, accessed November 2018.

Great read! I feel like one way that HHS can hack into the opinions and ideas of those “on the ground” is through hosting hack-a-thons around the country (especially in the towns most affected by opioid abuse). For me, the efficacy of the winning product is almost irrelevant. Yes, it would be amazing to create the perfect program to curb opioid abuse, but for the time being, the hack-a-thon is a means of getting communities talking. It stimulates ideas for how to solve the crisis which inherently reframes the issue as being solvable.

Loved this piece! Share your interest in applications of open innovation to the public sector. I think you raise an important question in your concluding thoughts, considering the tradeoff between holding one “flashy” competition and a more dispersed network of open innovation challenges. For me, the decision comes down to the variety of problems HHS is trying to solve: if they’re looking for a more holistic solution to the opioid epidemic, then a single challenge is the way to go. But to me, it feels like there are some clear “silos” in which they could hold a series of different innovation challenges to tackle different opioid epidemic-related problems (e.g. illicit drug use, prescription drug use, overdose treatment).

Thanks, Justin, for this insightful piece. Government agencies are perfectly positioned to use open innovation strategies to take advantage of the public’s knowledge and expertise for “big idea” projects while appropriately incentivizing and compensating valuable contributors. However, I wonder whether $10K and 50 teams is paltry and insufficient. How does incentive design in open innovation account for the appropriate “prize” level that can compete with private sector rewards for the same work?

I think for long term, non-emergency problems open innovation is an excellent solve. HHS should continue pursuing these open innovation challenges but I think you rightly recognize that computer code alone will not prevent someone with OUD from overdosing. This problem needs resources — and once that part is under control the coding can help manage and deploy those resources. Building out a digital infrastructure through open innovation is an important step towards the Department better responding to public health emergencies, but must happen in parallel with other resources that are deployed through those innovation vehicles.

Justin, this is very thought-provoking – thank you for sharing! Prior to HBS I worked with one of the start-ups that was awarded a $15,000 grant from CAMTech (MGH’s global health incubator) to launch a business called We Are Allies (WAA). WAA is an innovative nonprofit founded by a group of medical experts, pharmacists, military veterans, designers and people in long-term recovery addressing the opioid crisis by fighting the stigma of addiction and deploying the lifesaving overdose reversal drug naloxone into communities. Their goal is to help prevent opioid overdose deaths and to support our friends and neighbors suffering from addiction.

While they had an interesting pitch at the hackathon it has taken a lot of time (over a year) to curate a working business plan. While I’ve experienced two large challenges supporting this group I think the two key challenges with respect to hackathons trying to support solutions in the opioid space are: (1) the lack of customer (and in this case substance user) research and (2) the skills, resources, and time available to winners of hackathon teams. For hackathons to be more effective I think that, to your question, you could do a hybrid approach by hosting a hackathon and then opening up the idea for external feedback and actively seek feedback on the winning ideas from substance users. Getting their buy in and input early on in the ideation stage is integral to the initiative’ ssuccess.

Great post! One thought to add would be that moving towards better data as you suggest could also allow machine learning to play a larger role in this process. While innovation and creativity are certainly not areas in which machine learning today is very capable, the benefit ML brings is that it does not have any “pre-determined approach to addressing the opioid crisis”, but rather takes a purely correlation driven view of the data, which could potentially help spur original ideas in humans.

Great article Justin! I think the idea of open innovation for a huge problem like the opioid epidemic is really interesting. But aside from trying to address the opioid epidemic effectively, I wonder what goals HHS are exactly trying to accomplish through open innovation. Specifically, what value does open innovation provide to HHS/the opioid epidemic that simply funding solutions created by first responders/the community doesn’t provide? Is it that people don’t normally collaborate together and this provides them a chance to come up with better and more creative ideas? Or is HHS trying to create awareness and buy-in from the country through idea generation/implementation? I think this fundamentally shifts whether idea selections should be internal or external.

I think your point about exploitation vs exploration is also a great one and the tension here is as you mentioned–HHS doesn’t seem to have taken a side about which direction they want to head in. This drastically could reduce the potential success of projects they choose, and I agree that there should be a clear overarching direction.

Hey neighbor – great post! I think it is very intriguing to open up innovation on this type of sector. I’ve read of many companies using open innovation to fuel product development, but arguably this is more of a social reform. Perhaps there is more depth to these tournaments, but I wonder how much of the output is more hardware (i.e. systems, apps, devices) than software (i.e. policies, cultural reform). I think we need to be concerned that open innovation solves the right problem. Its an incredibly powerful tool, as you put so beautifully, but is it focusing on a symptom rather than the root cause? It reminds me of all those times that police crack down on drug traffic, which limits supply, drives up price and attracts new drug dealers. There’s a deeper societal issue that I think needs to be addressed for an open-innovation solution to have a long lasting effect.

This is a very interesting post, particularly given the magnitude and focus on the national issue of opioid abuse. “Hack-a-thons” and “code-a-thons” have are increasingly used amongst various fields and industries to drive innovative new ideas. Applying open innovation to the opioid epidemic is a very reasonable next step for HHS. And it’s certainly intriguing that several promising solutions stemmed from this 2017 Code-a-Thon. But I would echo Kaleigh’s concerns with respect to low information (on research of the end user) and skills and resources of the submission teams. Time will tell if the $10,000 prizes are creating sustainable and meaningful innovation. Justin, I agree that front-line providers need to be involved in these innovative efforts. I would also challenge HHS to incorporate health policy and public health expertise in these challenges. For instance, many physicians need additional training and licensing to prescribe suboxone (long-term treatment for tapering off opioid addiction) or administer naloxone (treatment for opiate overdose). How can solutions from these HHS challenges integrate new ideas and solutions to the opioid crisis into a complex healthcare landscape?

What a great application of open innovation! Although I do tend to agree with what you pointed out: That “tournaments will spur new ideas, but only ideas that align with a pre-determined approach to addressing the opioid crisis.” Because of this (and without any prior knowledge of or experience in the healthcare space) I think it might be beneficial to open up the idea generation process—but not the idea one. I think the sheer scope of the crisis implies that existing solutions are not going far enough, so bringing up more diversity of thought can only help. However, opening up idea selection is dangerous; allowing the non-expert general public to decide how to treat the drug-addicted doesn’t seem to be the best approach.

Thanks for the great read Justin! Regarding your second question, I think the primary complication that arises in applying open innovation to the opioid crisis is the level of regulation surrounding the medical industry. While all stakeholders are aligned on the objective of eliminating drug addiction and related deaths, the process of testing and iterating on new ideas can be slowed by restrictions around patient safety and data confidentiality (i.e. HIPAA). For this reason, I would suggest that HHS remain in control of idea selection and continue with innovation tournaments. The sheer number of constituent groups involved in this decision – patients, families, doctors, nurses, hospitals, insurance providers, and regulators among others – reinforces the importance of having a centralized decision-making body to help validate and share innovations across the industry. However, I do not believe that idea selection must be exclusively internal or external. Toward that end, I would also recommend experimenting with voting functionality to judge market support for certain innovations (similar to a like / dislike button on Facebook). The resulting data from these surveys could provide useful guidance on market sentiment to HHS as they make decisions.

Interesting article! To me interesting how prizes and competitions can be leveraged to spur innovation in the public sector. How you can unleash the power of the markets within what is traditionally a slower-moving bureaucracy ;). What I particularly like is that the article recognizes the limitations of “flashy contests” and notes the importance of the idea selectors, and the front-line health care professionals on the front-line. Really exciting what happens when the command and control idea selectors running a top-down program can effectively combine with the innovation from the bottom up. Like the reunification of East and West Berlin.