Unilever and Open Innovation: How does the emergence of digitally native brands change what it means to innovate?

Unilever's 400 brands have a new type of competitor: the digitally native brand. Can open innovation keep the organization nimble?

The startup threat

The emergence of digitally native consumer brands represents a new type of competitive threat for Unilever.

Since its founding in the 1920s, Unilever has played a key gatekeeper role in bringing products to consumers by controlling distribution through its brick-and-mortar retail partners [1]. When a small, up-and-coming brand wanted to sit on the shelves of a Walmart or Target, it’d typically sell itself to Unilever or one of its competitors, who could leverage its deep relationships to expand distribution and grow the brand.

In the last few years, the direct-to-consumer (DTC) business model emerged, allowing the creation of digitally native brands. Entrepreneurs can reach consumers directly by selling through an ecommerce website and shipping right to their homes. Successful brands can build a loyal following online and then expand to physical retail without Unilever’s help.

Unilever, which owns 400 brands and generated revenue of €53.7 billion in 2017 [2], used to primarily innovate by developing great new products for its existing portfolio of brands. But now, there’s innovation in how new brands themselves are built. Unilever is being forced to re-examine its approach to innovation in this new context.

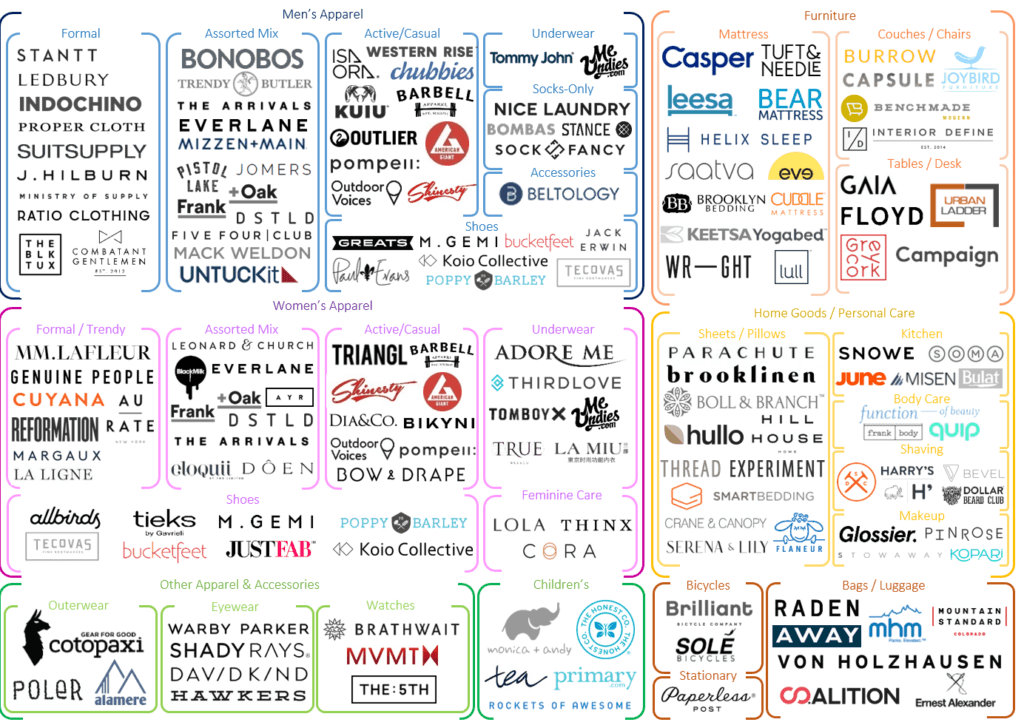

Examples of Digitally Native, Direct-to-Consumer Brands: DTC brands are disrupting nearly every consumer product category, including many that Unilever competes in. [3]

DTC brands are disrupting nearly every consumer product category, including many that Unilever competes in. [3]

Is open innovation a solution?

Unilever has long believed that open innovation — partnering with external parties like startups, academics, and individual inventors — is key to staying relevant in an increasingly competitive and global world. It started its implementation of the concept with its research and development (R&D) efforts. In a 2010 case study by Lancaster University, Unilever went as far as to say that “access [to innovation] is the new ownership.” [4] The company realized that even with €1 billion of R&D spend and an R&D staff of 6,200, not all great ideas relevant to Unilever brands would emerge from within the company. Unilever used open innovation to eliminate R&D “silos” and began conducting innovation efforts across brands and in collaboration with the outside world.

In the last several years, Unilever expanded its definition of “open innovation” to include supporting technology startups that could become valuable partners for its brands. These startups specialize in areas like enterprise technology and digital marketing platforms. Pursuing these partnerships is Unilever’s current medium-term focus as it relates to open innovation. Unilever launched The Foundry in May 2014 to partner with innovative startups that can enable Unilever to “pilot new technologies more efficiently, effectively, and speedily.” [5] The Foundry attracts startups by providing three primary benefits: marketing mentorship, financial rewards for startups whose ideas address briefs Unilever posts, and access to Unilever Ventures, the firm’s investing arm. This approach gives startups an entry point to work with a large company like Unilever and gives Unilever the chance to see the latest technological innovations sooner.

The emergence of digitally native brands raises the question of whether Unilever should expand its definition of open innovation further. Unilever could become a partner to startup brands as a way to insulate itself from the competitive threat the new brands represent. The Foundry, to date, has not addressed this opportunity. Instead, it continues to focus on bringing emerging technological capabilities to its set of established brands. But what about a form of open innovation that might enable Unilever to invest in or acquire valuable brands when they’re still early-stage startups?

Unilever’s short-term strategy has been to acquire brands (and thus their innovation) where their own approach to open innovation has come up short. Since the start of 2015, Unilever has made 18 acquisitions. [6] The high valuations of these rapidly growing businesses show how expensive this approach can be. In 2016, for example, Unilever spent $1 billion to acquire Dollar Shave Club, an ecommerce shaving company, for a valuation of five times revenue. [7] In the same year, Unilever purchased Seventh Generation, a natural household cleaning brand, for between $600M and $700M. [8] Had The Foundry had a hand in developing these brands from the start, Unilever may have had an opportunity to acquire them earlier at a lower price.

Recommendations

Unilever should evolve its approach to open innovation given the emergence of digitally native brands. Three steps to do so include:

- (Short-Term) Expand the mission of The Foundry to include incubating emerging consumer brands. The Foundry already coordinates Unilever’s efforts to partner with external groups. Unilever should broaden its mandate.

- (Medium-Term) Attract startups to an incubator program by offering benefits that matter most to entrepreneurs. The Foundry can offer things like discounted workspace, marketing and branding mentorship, and access to capital.

- (Medium-Term) Allow brands in The Foundry’s program to tap into the digitally native brands that Unilever already acquired, such as Dollar Shave Club. This could include mentorship by the founders and access to relevant subject-matter experts within the brands’ organizations.

Outstanding Questions

- Is it realistic for Unilever to identify promising brands earlier, or is this too far from their core strengths as an organization? For most of the company’s history, it purchased brands that already showed signs of promise and expanded distribution. Can Unilever develop this new capability quickly?

(766 words)

[1] “1920 – 1929: Unilever is formed”, Unilever Website, accessed November 12, 2018, https://www.unilever.co.uk/about/who-we-are/our-history/1920-1929.html

[2] Unilever Annual Report, 2017, https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-annual-report-and-accounts-2017_tcm244-516456_en.pdf

[3] ” Subscription E-Commerce Market Map,” CB Insights, accessed November 11, 2018, https://www.cbinsights.com/research/industry-market-map-landscape/

[4] Decter, M; Mather, A; & Garner, C. Institute of Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development, Lancaster University, http://www.academia.edu/6133963/Access_is_the_new_ownership_a_case_study_of_Unilevers_approach_to_open_innovation

[5]Unilever Press Release, May 22, 2014, “Unilever launches global platform to engage with start-ups,” https://www.unilever.com/news/press-releases/2014/14-05-22-Unilever-launches-global-platform-to-engage-with-start-ups.html

[6] “Acquisitions and Disposals”, Unilever Website, accessed November 11, 2018, https://www.unilever.com/investor-relations/understanding-unilever/acquisitions-and-disposals/

[7] Alan Livsey, Financial Times, March 16, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/9bb5cc54-d368-11e6-b06b-680c49b4b4c0

[8] “Mega-Merger Target Unilever Is Highly Active in Private Markets,” CB Insights, February 17, 2017, https://www.cbinsights.com/research/unilever-investment-acquisitions/

You pose some interesting questions. I completely agree that Unilever missed an opportunity by not only acquiring but also looking at this disruptive DTC ecosystem as a chance to start incubating and protecting themselves from the risk of these disruptive companies. In the food and beverage space, KraftHeinz just launched a venture this year called Springboard which aims to achieve just this – it is an internal incubator that nurtures both external small and promising startups, as well as new internal small brands. The objective is to help balance their brand portfolio to compete within the natural food space that is trending within the industry. I think Unilever could definitely benefit from a similar program and has the resources to do so.

In response to your question, I believe it is realistic for Unilever to identify promising brands earlier through The Foundry. I agree that it makes more sense for Unilever to approach partnerships with startups this way than to manage its open innovation platform around the idea of startups building technologies specifically for Unilever’s portfolio. In this way, Unilever has a larger addressable market of entrepreneurs to scout. That being said, even with this shift in open innovation I challenge the potential for significant change this would actually have on Unilever’s prospects in competing in the rapidly changing consumer product space. Companies such as General Mills have created similar partnerships through 301inc which have led to minimal impact on the overall prospects of the company. With such fragmentation in the industry, companies like Unilever would have to make a multitude of correct bets in partnering with the right startups early on leading to acquisitions to have the sort of scaled financial impact that Unilever is seeking.

I completely agree with your suggestion that Unilever needs to lean in further to more open innovation with the rise of DTC companies. Proctor & Gamble has actually taken a large step in this direction with their Connect & Develop website. Especially at at time when big CPG companies like P&G and Unilever are facing shrinking margins in their traditional business lines, the need for innovation outside of their normal course of business is crucial.

To answer your question, I believe it makes sense for Unilever to identify promising brands early on and it’s actually not too far away from their core strengths – they already have Unilever Ventures which I believe is the venture capital investment arm of the company, and they have profound product marketing knowledge and geographical expertise within specific market to make reasonable investment decisions. Another source of innovation I can think of is internal / customer product innovation, with product innovation ideas coming from employees and customers – I believe 3M is a leader in that area. Given Unilever’s proximity to customers, this can be another potential area for them to look into.

In this highly competitive environment, I think it is critical for Unilever to try to identify promising brands and acquire them earlier in their lifecycles at more reasonable valuations. Leveraging The Foundry and Unilever Ventures is a good way to do this, providing both a benefit to the startups of mentorship, brand name, marketing advice/support, and logistics support while reaping the financial, open innovation, and synergistic benefits of the startups. [1] A lot of large companies, such as Alibaba, Rakuten, Google, etc are forming internal venture capital arms to compete in this space, and thus it is very difficult to differentiate yourself and win deals.

[1] http://www.unileverventures.com/.

Interesting piece! As I read this, The Foundry almost seemed like a Venture Capital firm to me. Is Unilever best equipped to be a Venture Capital firm? Beyond investing, Unilever could leverage its experience and success with a variety of products to help startups with best practices – from marketing to distribution to manufacturing. Many startups struggle with these functions in the early days and would be willing to give up equity to get Unilevers support in these areas. They could also encourage innovation in emerging markets where innovators may not have the tools to bring their ideas to life.

I agree with some of the sentiments above that developing a consumer product-focused VC arm may prove very difficult just based on the competitiveness of that industry and the challenge of building that capability out organically, since it would likely require building out a new team. I think in technology VC, where Foundry is playing, it may be slightly easier to determine whether a startup’s technology has the potential to be disruptive or how it could benefit Unilever than it might be to determine which consumer startup brands have the potential to connect with consumers and explode. I also think this would force Unilever to walk a pretty thin line between supporting its existing brands as well as its startup businesses, which would presumably be in direct competition with Unilever’s existing brands.

Great article ! Thank you for sharing.

It’s interesting to realize how hard it is for very large and established company to truly innovate. Unilever is definitely not the only company to innovate buy buying new successful start-up and leverage its large operations to generate economies of scale : google, Facebook and amazon do the same things.

Regarding your question, could the Foundry become a venture capital firm, I believe it could. It already has managed to build a structure that is suitable to be transformed in a VC. I think that their challenge now is to recruit the right person to run the VC fund, ideally poach someone from a VC specialized in consumer goods.

The idea of using a VC to inorganically grow its innovation capabilities is an interesting one, particularly when you’re looking at companies that are as large as Unilever. It seems that even if this is not within their core capability, they will be able to execute on this initiative simply due to their size. The opportunity that they may be missing out on is actually receiving organic innovation suggestions/recommendations. There was a comment above regarding Unilever’s proximity to its customers, and I believe that this is an important dynamic in their business. I see disruption in the space not so much in terms of technical capability, but flexibility and adaptability in reacting to what the customer needs. Unilever can address this by creating open innovation that listens more closely to its customers. Taking this further, I believe that a local approach here is appropriate. As a multinational operating in more than 190 countries, capturing the local perspective in each of its product lines is critical to success. That said, I recommend that the company move toward a more organic and local approach to its open innovation efforts.

In my opinion it is very realistic for Unilever to identify promising brands earlier if they partner up with startups or academia. They will see a huge benefit in diversifying their products and getting into very new and trendy products. I think they can develop the capability quickly if they set up the collaboration correctly, their management teams and the communication part with the new partners. The only problem that I would find more difficult to solve is how are they going to avoid all the patent clashes and the proprietary information. Since Unilever is a for profit organization they need to have some very specific contracts on where the profit will go if they partner with startups/academia without completely buying the brands.

Really interesting article! I definitely agree that these D2C startups are a big threat not just because they’re more innovative, but I think they have a natural brand advantage, where millennial consumers are willing to pay more for a “startup” product then one produced by a conglomerate (e.g. Away). This unfortunately erodes Unilever’s scale advantage.

To answer your question, I actually don’t think Unilever can identify promising brands early. In general, corporate VC/incubator arms have lower success rates than a regular VC. One reason for this is a corporate program tends to inhibit the exact innovation they are trying to produce. As a result corporate VCs are generally seen as less attractive investors to a startup, so popular companies with multiple funding options usually go with other investors (excluding top tech cos.). I think if Unilever had the ability to identify these companies, they would also have the ability to produce similar ideas in house.

I actually agree with Unilever’s strategy of acquiring companies in the ~$500M range. At that size they have already established the brand in the eyes of consumers and are large enough to operate fairly independently once acquired. Additionally they are big enough where they can take full advantage of Unilever’s scale in distribution and production. This also provides the influx of outside innovation they need, but at a scale where it can actually be infused within the organization. In combination I would source ideas straight from consumers by holding case competitions or having open submission contests. This brings innovation into the company at the ideation stage where Unilever can take advantage of their own production process. I believe this provides the same upside and risk as a VC/incubator but gives them significantly more control and allows them to lean into their own core capabilities.

This is a good article to explain how a large, mature company can drive innovation by seeking opportunities outside its organization. To the question raised, I think Unilever will be able to and need to identify promising brands and bringing them into its supply chain identify promising brands earlier in order to stay ahead of fierce competition. If they can look into startups not only in the U.S. but also in global markets, they can get more benefits from its extended open innovation.

In terms of extending open innovation, Unilever may explore broader players in open innovation ecosystem such as suppliers, employees, and strategic partners in order to seek ideas from stakeholders with different perspectives. There may be suppliers that can provide new product ideas based on their working relationships with multiple big brands. Employees in non-product development functions may have good product ideas. Unilever may also seek more collaboration with strategic partners such as research centers in FMCG industry. Limiting open innovation to just consumers and young brands may limit sources for innovation.

Especially, since Unilever says “We anticipate that around 70% of our innovations are linked to working with our strategic suppliers. That’s why we invest in mutually-beneficial relationships with our key suppliers so we can share capabilities and co-innovate for shared growth.”, they had better check whether they have a strong mechanism to effectively pull their suppliers in open innovation.

Forgot to post the source for the last paragraph above (https://www.unilever.com/about/suppliers-centre/working-together/). I will look forward to seeing Unilever succesfully utilize its broadened open innovation!