The insatiable appetite of climate change

As global warming impacts food security, Cargill must ensure that the world doesn’t go hungry.

“As the world warms, a lot of adaptation will be required; where we are growing, the types of crops we are growing, and genetics” – Tony Nugteren, Assistant Vice President at Cargill1

Climate change is eating your food!

2016 has been the 3rd consecutive hottest year since recordkeeping began and the scientific community attributes this to human emissions of greenhouse gases2. At this rate, by 2100, the world could end up 5 degree Celsius hotter3.

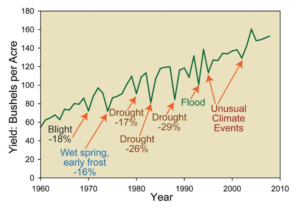

How will this impact the food we eat? A LOT! Crop yields are sensitive to climate change such as extreme precipitation and temperature variations. Don’t believe me? Look at the chart below.

In the United States, the Midwest and Southern states risk up to a 50%-70% loss in average annual crop yields (corn, soy, cotton, and wheat), without agricultural adaptation, per a report by ‘The Risky Business Project’7. The report also goes on to predict that the Midwest will likely see overall agricultural losses for corn and wheat of 11%-69% across the region by 21008.

Cargill should be worried, or shouldn’t it?

Cargill is the largest privately owned company in the US9 with a focus on providing food, beverage, and agricultural products to the world. Their revenues totaled $107.2B and (adjusted) net earnings $2.38B in fiscal 2016.

Given its dependence on crops, Cargill’s operations and finances are inherently linked to the risks of climate change. For example, Cargill’s Q4 profits in 2014 dropped by 12% as a 4-year drought in the U.S. Southwest damaged pastures used to raise cows10. Such instances will only increase in frequency and intensity going forward as higher temperatures, variable precipitation, and water constraints lower crop quality and yields.

While Cargill accepts these risks, it is fascinating that it remains optimistic about sustaining its operations, driven by a strong belief in the ‘systemic resilience of agriculture’ and the ‘ingenuity of the world’s farmers’12. Cargill’s optimism goes so far as to state that “we are optimistic that the world can feed itself”13.

While this seems like a marketing gimmick on the face of it, designed to perhaps boost the confidence of its stakeholders, on digging deeper I found that Cargill is indeed walking the talk, taking targeted and strategic steps to both mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Cargill’s fight against climate change

MIT’s joint program on the science and policy of global change (which Cargill has sponsored since 2008) points out the dual cause and effect relationship between climate change and agriculture – while climate change impacts agriculture, agriculture contributes to climate change as well. It does so in 2 main ways -one, by contributing to greenhouse gas emissions (20-25% of total emissions) and two, by causing deforestation14.

Cargill is trying to address this through mitigation and adaptation efforts:

- Reducing environmental impact of their operations: In the last decade, Cargill has improved energy efficiency by 16%, carbon intensity by 9%, and freshwater efficiency by 12%. It also plans to increase renewable energy use by 4% (share of total energy use)15.

- Raising awareness and encouraging dialogue about the economic risks of climate change on food and agriculture. This can catalyze genesis of mitigative and adaptive solutions15.

- Committing to end deforestation by working across stakeholders including farmers, government, business, advocacy organizations, and consumers16. One such partnership is with the World Resources Institute to implement no-deforestation commitments with palm oil production17.

Can’t you do more, Cargill?

While Cargill’s efforts are noteworthy, they should be doing much more. For example:

- Identify and invest in technological solutions that help adapt to climate change. For instance, one such promising agricultural technology startup – Agrilyst – is an indoor-farm with better water retention, longer “sun” hours through LED lights, and adjustable CO2 levels, aimed at mirroring a ‘conducive climate of the past’ to help grow crops better18

- Promote and practice sustainable sourcing of crops. This includes encouraging farmers to undertake sustainable farming and researching and developing more resilient raw materials. They wouldn’t be the first to do this though – Unilever is targeting to source 100% of its agricultural raw materials sustainably by 202020.

The costs of mitigating climate change will likely be in the range of $140–$175 billion per year by 203021. The question remains – who will pay that cost?

Word Count: 794 (without citations)

Endnotes

1 Brenda Bouw , “How Rising Global Temperatures And Extreme Weather Will Change Farming”, Forbes, July 11, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/cargill/2016/07/11/how-rising-global-temperatures-change-farming/#442040df4219, accessed November 2016.

2 Rebecca A. Henderson et al., “Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business,” HBS No. N2-317-032 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), pg. 2.

3 IPCC, 2014: Summary for policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L.White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 13-14.

4 Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States, Thomas R. Karl, Jerry M. Melillo, and Thomas C. Peterson, (eds.). Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 74.

5 USGCRP (2014). Hatfield, J., G. Takle, R. Grotjahn, P. Holden, R. C. Izaurralde, T. Mader, E. Marshall, and D. Liverman, 2014: Ch. 6: Agriculture. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J. M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G. W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 150-174.

6 Scheherazade Daneshkhu, “Climate change raises risk to food supplies,” FT.com, April 10, 2014, ABI/INFORM via ProQuest, accessed November 2016.

7 Michael R. Bloomberg et al., “The Economic Risks of Climate Change in the United States,” The Risky Business Project (June 2014), p. 5, http://riskybusiness.org/site/assets/uploads/2015/09/RiskyBusiness_Report_WEB_09_08_14.pdf, accessed November 2016.

8 “Risky Business Project Finds Midwest Agriculture, Labor and Manufacturing Industries May Face Economic Risk from Climate Change: Results Show that America’s Heartland Risks Economic Disruptions as Climate Change Advances, Reduces Labor Productivity, and Shifts Agricultural Production Patterns,” PR Newswire [New York], January 23, 2015, ABI/INFORM via ProQuest, accessed November 2016.

9 Andrea Murphy , “America’s Largest Private Companies 2016”, Forbes, July 20, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/andreamurphy/2016/07/20/americas-largest-private-companies-2016/#1a70d8c51417, accessed November 2016.

10 Eliza Roberts et al., “Feeding Ourselves Thirsty: How the Food Sector is Managing Global Water Risks”, A Ceres Report (May 2015), Ceres, https://www.ceres.org/resources/reports/feeding-ourselves-thirsty-how-the-food-sector-is-managing-global-water-risks, accessed November 2016.

11 Oklahoma Farm Report, “Farm Bureau Urges Support for Fruit, Veggie Farmers”, April 24, 2013, http://oklahomafarmreport.com/wire/news/2013/04/06301_FruitVeggieProgram04242013_101451.php#.WBz0wforI2y, accessed November 2016.

12 Cargill, “What are the implications of climate change for agriculture and Cargill?”, http://www.cargill.com/news/issues/food-security/climate-change/index.jsp, accessed November 2016.

13 Ibid.

14 MIT Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, “In the News: Climate change, agriculture and food security”, July 17, 2013, http://globalchange.mit.edu/news-events/news/news_id/294#.WBz1xforI2z, accessed November 2016.

15 Cargill, “Five ways Cargill is addressing climate change”, http://www.cargill.com/connections/five-ways-cargill-is-addressing-climate-change/index.jsp, accessed November 2016.

16 Cargill, “Cargill marks anniversary of no-deforestation pledge with new forest policy”, Minneapolis, September 17, 2015, http://www.cargill.com/news/releases/2015/NA31891862.jsp, accessed November 2016.

17 “Cargill, WRI Partner to Monitor and Manage Deforestation and Water Risk Across Supply Chains: – Partnership will help expand WRI’s cutting-edge tools to the agriculture sector on a global scale”, PR Newswire [New York], March 21, 2016, ABI/INFORM via ProQuest, accessed November 2016.

18 Heather Smith, “Will climate change move agriculture indoors? And will that be a good thing?”, Grist, February 3, 2016, http://grist.org/food/will-climate-change-move-agriculture-indoors-and-will-that-be-a-good-thing/, accessed November 2016.

19 Louise Burwood-Taylor, “3 Big Challenges for Indoor Agriculture”, AgFunder News, October 17, 2015, https://agfundernews.com/3-big-challenges-for-indoor-agriculture4864.html, accessed November 2016.

20 Sarantis Michalopoulos, “Food industry focuses on sustainable sourcing to mitigate climate change”, EurActiv.com, November 20, 2015, http://www.euractiv.com/section/food-chain-sustainability/news/food-industry-focuses-on-sustainable-sourcing-to-mitigate-climate-change/, accessed November 2016.

21 Dimitris Tsitsiragos, “Climate change is a threat – and an opportunity – for the private sector”, Capital Finance International magazine, The World Bank, January 13, 2016, http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/opinion/2016/01/13/climate-change-is-a-threat—and-an-opportunity—for-the-private-sector, accessed November 2016.

Saurav you make an excellent point regarding Cargill’s dependence on climate change, and I agree that they should be doing more to address the issue. Food security is extremely important, and I think we can take a different perspective on what Cargill should do if we also take into account the mix of nutrients that they are producing. The vast majority of crop calories are in the form of carbohydrates, and if climate change begins to affect production of certain crops, we could switch to more calorie-dense crops to maintain overall calorie production stable. However the same is not true for proteins, we have far less flexibility in terms of protein production, and I would be very interested to understand what Cargill might be doing to increase efficiency and security of protein production.

That’s a great point, Javi! I hadn’t thought of that. Maybe they could even partner with companies like Indigo agriculture to boost the production of calorie dense crops in areas which are still capable of producing those crops after climate change impact!

This is a very interesting article Saurav! I’m impressed Cargill has such an optimistic attitude regarding climate change, considering it has caused large losses for the company in the past (such as the Q4 2014 drought effect that you pointed out). I suppose that despite the volatility shown in the first chart, yields per acre are still improving over time in the U.S.

I completely agree that a main area of focus for Cargill going forward should be identifying and investing in new technology. In addition, as a global company, I believe that Cargill should have a global lens when looking for innovation in agriculture. As an example, Cargill could partner with organizations engaging in digital soil mapping, such as the Africa Soil Information Service funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which provides key data for natural resource management and sustainable agriculture in data-sparse regions.

Fantastic suggestion, Ana! They should definitely be doing that. Not just that, like I responded to Javi above, they could even partner with biotech companies like Indigo agriculture to produce high nutrient / calorie crops in areas so as to account for variations in global food supply because of climate change!

Saurav, this was a very compelling read. I find it interesting that, in my opinion, Cargill’s declaration almost sidesteps the chief issue. While they boldly declare that “we are optimistic that the world can feed itself,” it seems to me that this is actually not the foremost concern. It’s not food production that is most at risk– it is food availability. Roughly one-third of the world’s global food production– some 1.3 billion tons per year– gets lost or wasted [1]; meanwhile, nearly 800 million people around the world do not have sufficient food to live a healthy life. [2] Mapping a better solution to get current food production into the hands of those who need it most– and doing so in a climate-friendly manner with regard to transportation of these calories– should be the chief, near-to-medium-term concern. For reference, food transportation has risen far faster than food production: in the thirty years up to 1998, “world food production increased by 84 percent and the population by 91 percent, but food trade increased 184 percent.” [3]. By the mid-2000s, the typical American prepared meal contained, on average, ingredients from at least 5 other countries. [3]

Focusing primarily on tackling this food availability/transportation problem while simultaneously investing for the long term in more climate-friendly food production techniques overall seems like a good path forward–and it is concerning to see that Cargill’s priorities may not align with this objective.

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, http://www.fao.org/save-food/resources/keyfindings/en/, accessed Nov 2016

[2] World Food Programme, Hunger Statistics, https://www.wfp.org/hunger/stats, accessed Nov 2016

[3] ‘Health Facts,’ Natural Resource Defense Council, 2007, https://food-hub.org/files/resources/Food%20Miles.pdf, accessed Nov 2016

You’re spot on — I hadn’t thought about the misalignment between food availability and supply as you point out. Something tells me though that that problem is more like what a government / groups of governments need to tackle unless they can offer Cargill an incentive to push forward on what may be more a social good than a benefit to its bottomline.