Gazprom: Ready to Respond

The Russian state-owned energy company is positioned to respond to global efforts to address climate change.

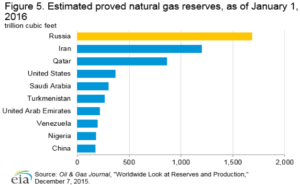

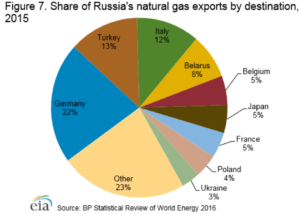

The Russian state-owned energy company Gazprom is in a fantastic position to respond to global efforts to address climate change. By extension, global climate action is also a geopolitical opportunity for Russia, which owns over 50% of the publicly traded Gazprom. Gazprom is, by far, the largest producer of natural gas in the world[1], supplying methane to Europe and, increasingly, China[2].

Limited to combustion driven processes due to its molecular simplicity, methane is primarily used in heating, electricity generation, and manufacturing feedstock applications. In these applications, substituting the incumbent energy source coal with natural gas can result in almost 50% less carbon dioxide emissions for the same amount energy released[3].

Pounds of Carbon Dioxide emitted per

million British thermal units (Btu) of energy

| Coal (anthracite) |

228.6 |

| Coal (bituminous) | 205.7 |

| Coal (lignite) | 215.4 |

| Coal (subbituminous) | 214.3 |

| Propane | 139.0 |

| Natural gas | 117.0 |

In the future, increasingly aggressive global regulations of the coal industry will continue, a result of international agreements aimed at capping carbon dioxide emissions[4]. This will create a void in affordable energy supply specifically in Europe, with Russian natural gas best positioned to fill the global gap. Through Gazprom investments, Russia will be positioned to expand its political influence over Europe by supplying reliable, affordable energy to countries neglecting the policies and investment to support the development of their domestic, economically viable energy resources.

Russian oil and gas pipeline network[5]

Russia has high concentrations of cheap natural gas across its expansive terrain. Gas resources in Russia have significant production spread across a decades-long, plateaued depletion profile. These lengthy production profiles empower Gazprom’s fundamental business strategy of building pipelines to supply gas to nations requiring affordable, heat-generating sources of energy. While building pipelines can be expensive, Gazprom is positioned to leverage the relationship with the Russian government to increase access to new resources and the pipelines required to transport methane to increasingly desperate markets.

One of the primary global climate change skeptics[6], Russia will use Gazprom to take advantage of the developed world’s attempt to make coal obsolete. Gazprom will be positioned to expand the influence and materiality of their agreements to supply baseload energy to European countries that are eagerly turning their backs on economically viable energy policy.[7] As European countries continue to subsidize energy sources[8] that are not cost competitive with fossil fuels[9], Gazprom will ramp up production through increased drilling and operational maintenance, benefiting from the structural futility of Europe’s efforts[10].

Through increased investment in drilling and operations, Gazprom will provide natural gas to eastern European economies. With the understanding that democracies vote, and no one votes for cold showers, these countries will be increasingly indebted to Gazprom and Russia for supplying affordable energy. In Ukraine and the conflict over Crimea, we have recently seen the economic and military consequences of neglecting this symbiotic relationship[11]. Russia, sitting on the cheapest (and most geopolitically stable) supply of energy in the region, will ultimately be preferred to the riskier Middle Eastern reserves as well as to the much more expensive liquefied natural gas being transported from North America, Africa, and Asia.

In conclusion, in attempting to address climate change, global governments are unintentionally exacerbating one of Europe’s biggest problems, influence of Russian gas. Gazprom, the world’s largest natural gas producer, stands to benefit tremendously from this folly. (798 words)

[1] Robert Rapier, “The Top 10 Natural Gas Producers,” Forbes, Energy, #PowerUp (blog), Forbes, August 12, 2016, http://www.forbes.com/sites/rrapier/2016/08/12/the-top-10-natural-gas-producers/#5962b9333f7a, accessed November 2016.

[2] Gazprom Export. 2014. China. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/partners/china/. [Accessed 4 November 2016].

[3] “Frequently Asked Questions,” Independent Statistics & Analysis U.S. Energy Information Administration, June 14, 2016, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.cfm?id=73&t=11, accessed November 2016.

[4] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2014. Kyoto Protocol. [ONLINE] Available at: http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php. [Accessed 4 November 2016].

[5] The Asia-Pacific Journal. 2008. Russian ‘Power Politics’, North Korea and the Future of Northeast Asia. [ONLINE] Available at: http://apjjf.org/-Leonid-Petrov/2835/article.html. [Accessed 4 November 2016].

[6] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business,” HBS No. N2-317-032 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), pg. 13, Exhibit 1.

[7] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business,” HBS No. N2-317-032 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), pg. 26, Exhibit 21.

[8] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business,” HBS No. N2-317-032 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), pg. 28, Exhibit 22.

[9] Rebecca Henderson, Sophus Reinert, Polina Dekhtyar, and Amram Migdal, “Climate Change in 2016: Implications for Business,” HBS No. N2-317-032 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2016), pg. 25, Exhibit 19.

[10] Sacha Alberici, Sil Boeve, et.al.. 2014. Subsidies and costs of EU energy. [ONLINE] Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/ECOFYS%202014%20Subsidies%20and%20costs%20of%20EU%20energy_11_Nov.pdf. [Accessed 4 November 2016].

[11] Paul Kirby. 2014. Russia’s gas fight with Ukraine. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29521564. [Accessed 4 November 2016].

When you say that European countries are “eagerly turning their backs on economically viable energy policy,” you are implying that a policy of increasing renewable energy production is not economically viable. And you have a point — after all, you point out the reliability of fossil fuels, something solar, wind, and other energy forms can’t match.

But the European Union is committed to sourcing 20% of their energy from renewable sources by 2020 and 27% by 2030. [1] They’re currently at 13% renewable, and 17% from “solid products,” which I assume is mostly coal. [2] If they meet their goals and use all of their increase in renewable energy to replace coal, leaving all else equal, they will be down to 10% solid products by 2020 and down to 3% by 2030.

Does Gazprom’s excellent positioning rely on Europe phasing out coal by 2020 or 2030, thus allowing Gazprom to capture the 3-10% of solid products that renewable energy hasn’t replaced? Or does your implied argument that renewable energy efforts aren’t viable mean you think Europe cannot meet its 20% and 27% targets, and will thus need to rely on natural gas even more as it phases out coal?

[1] https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/renewable-energy

[2] European Union Energy in Figures Statistical Pocketbook 2016, page 21, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/pocketbook_energy-2016_web-final_final.pdf%5D

I agree with MDLB that the European Union has already planed to move away from BOTH fossil fuel sources (natural gas and coal) AND Europe’s heavy reliance on Russia (via Gazprom). Although natural gas is considerably cleaner than coal in terms of carbon footprint, I believe that the EU acknowledges that natural gas is still much more polluted that renewables sources such as wind and solar which they consider to be more sustainable long term. In fact, we can see in recent years that the EU has already made some strategic decisions to pursue renewable energy sources and curtail its reliance on natural gas.

– https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/feb/02/germany-leads-europe-in-offshore-wind-energy-growth

– http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/17/business/energy-environment/european-union-seeks-to-reduce-reliance-on-russian-gas.html?_r=0

Hey Pat – undoubtedly there is a plan, the question is whether the plan is sustainable. Germany already pays 3x the US cost because of their policies on renewables.

(https://www.google.com/amp/www.forbes.com/sites/michaellynch/2016/02/19/negative-electricity-prices-are-not-a-sign-of-renewable-success/)

Further, European GDP growth has stagnated and cannot support costly energy policy in the long run. Even if these countries were in a fantastic position to subsidized alternative technologies, these countries are not located in a position with access to the highest quality alternative energy sources. Solar is better suited for use in the Middle East, Africa, etc. while wind is more effective on the coast. Russia will continue to wield increasing influence over those countries that cannot economically support these technologies long-term.

(http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/eu/forecasts/2016_spring_forecast_en.htm)

(http://globalchange.mit.edu/files/document/MITJPSPGC_Rpt268.pdf)

(http://globalchange.mit.edu/files/document/MITJPSPGC_Rpt258.pdf)