Telemedicine: Removing the “Borders” in Doctors Without Borders

MSF's mission to save lives in war-torn regions comes with great human and financial costs. Can telemedicine help overcome these challenges?

“Somalia has been at war for two decades. Since [ex-patriate staff] were subject to kidnapping and direct risk by fundamentalist groups and militias,… the only approach we could follow was remote control strategies.” –Latifa Ayada, MSF Brussels

The Costs of MSF’s Mission

Doctors Without Borders or Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is an international NGO dedicated to providing health services to war-torn regions and developing countries facing endemic diseases. Since its founding in 1971, the organization has been a bulwark of humanitarianism, often at the critique of pragmatists.

Frequently working in controversial and politically charged regions, MSF has paid great costs to stay true to its  mission.

mission.

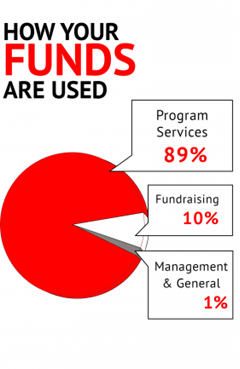

Financially, MSF is 92% dependent on private donors supporting an annual budget of $1.4 billion1. The organization often denies funds in conflict with its mission, refusing, for example, $63 million from the European Union in response to “shameful deterrence policies” blocking refugees from Europe in June 20162. MSF is also very careful with donations it receives. In October 2016, MSF refused a million free pneumococcal children’s vaccines from Pfizer3, arguing that the high cost of the vaccine had been a larger contributor to the 1.4 million annual child deaths from pneumonia than the value of the free vaccines. As MSF Executive Director Jason Cone put it, donations are “often used as a way to make others ‘pay up.’ By giving [their products] away for free, pharmaceutical corporations can use this as justification for why prices remain high for others, including other humanitarian organizations and developing countries that also can’t afford [them].”

MSF’s mission of servicing war-torn regions also comes with high human costs. In October 2015, the NGO’s Afghan hospital serving those caught in the crosshairs of Taliban fighting was erroneously bombed by US airstrikes, destroying the hospital and leaving 42 dead4.

Telemedicine as an Intervention

Telemedicine—the use of telecommunication and information technology (IT) to provide clinical health care from a distance— has been a tremendous recent asset in overcoming MSF’s political, economic and humanitarian challenges. Advances in web connectivity and data sharing have driven three modalities of telemedicine used by MSF: store and forward (SAF), remote monitoring (RM) and live interactive (LI) systems5.

The most common of the three, SAF involves transmitting medical data such as x-rays and pathology images to medical specialists to read remotely at a later convenient time. Specialties reliant on expert analysis of visual data—such as dermatology, radiology, and pathology—have been best suited in this model.

Similar to SAF, RM telemedicine uses biometric data being transmitted to medical professionals, but with real time feedback. Data-gathering medical devices used for chronic conditions—such as dialysis machines, cardiac pacemakers and insulin pumps—have been most used through this model.

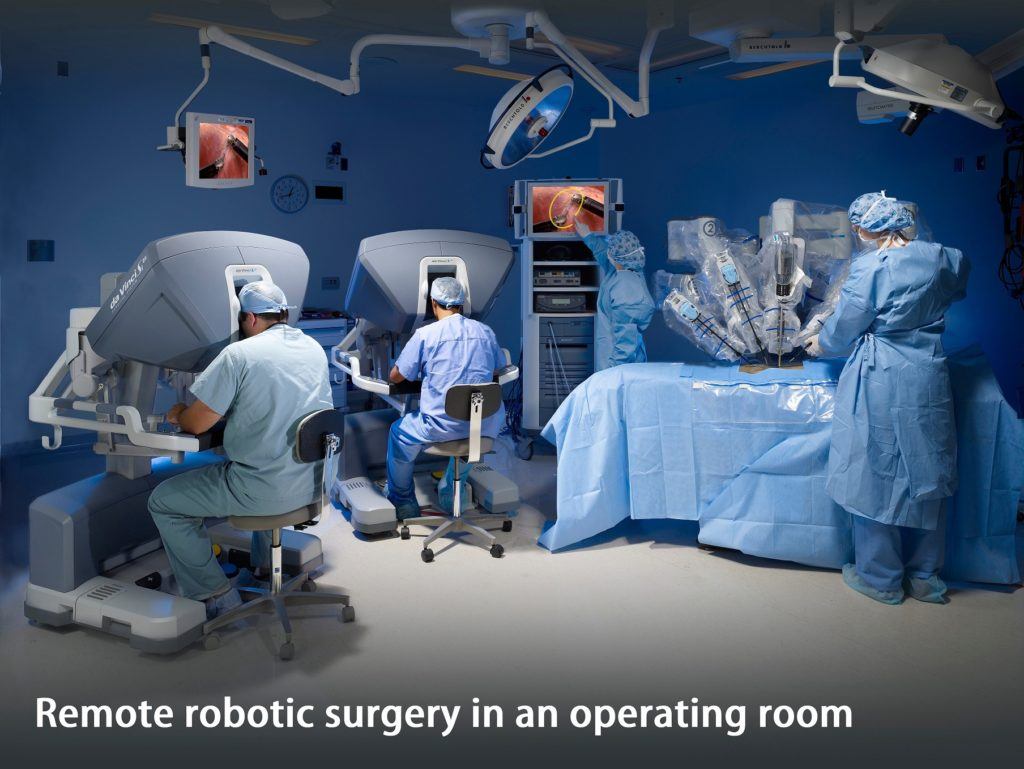

Finally, LI telemedicine involves real-time video-conferencing interactions among patients and providers. This tool has been most relevant in situations where high-granularity physical exams may not be needed, such as remote psychiatric evaluations or medical history reviews. Most recently, a variant of the live model has also been explored with robotic surgery6. Among robotically-compatible surgical fields such as urology and general surgery, robots are already used remotely within hospital systems.

Impact of Telemedicine

The main strength of telemedicine for MSF has been its ability to provide access to healthcare in dangerous, underserved areas and efficient training through education by remote experts.

The main strength of telemedicine for MSF has been its ability to provide access to healthcare in dangerous, underserved areas and efficient training through education by remote experts.

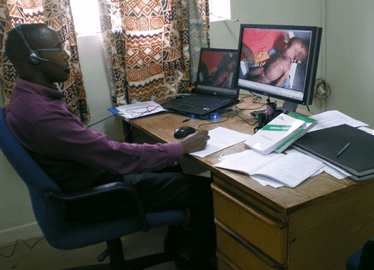

The results of the telemedicine programs MSF has implemented have been profound. In Somalia, for example, an SAF and LI teleconsultation service was set up for an MSF pediatric ward because of the high safety risk to ex-patriated Somali MSF personnel who wanted to continue treating their patients7. With the implementation of the service, consultations increased from 10 to 90 per month over a year. Of these teleconsults, 56% added significant diagnoses, 25% caught missed life-threatening conditions and 64% had their clinical management plan significantly altered by the consultation.

The cost of the telemedical system was also significantly less than that of traditional in-person clinical services. Total system costs were €20,000 a year. In contrast, because of safety risks and charter plane costs, transportation of personnel to Somali MSF stations cost €17,000 per trip.

Next Steps

Although telemedicine has been an important asset for MSF, widespread proliferation of the technology has not yet been adopted due to infrastructural challenges8. Many war-torn areas lack access to high-tech facilities and high-speed web connectivity needed to collect and transmit the data that capitalize these services. In developed nations where the provider side of telemedical services may be stationed, adoption of telemedicine infrastructure has been slow due to concerns about liability, reimbursement and privacy9,10.

In addressing these challenges MSF can proceed with the following four steps:

- Invest in infrastructure in underserved markets and update clinic IT systems and diagnostics in order to collect data capitalizable in telemedical services.

- Partner with domestic telemedicine programs to build a network of specialists across the world that are plugged into MSF’s telemedicine consultation portal.

- Network MSF clinics together through an MSF telemedicine portal.

- Focus on SAF/LI teleconsultation services to capitalize on existing generalist networks.

(800 words)

- “MSF International Activity Report 2015.” Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International. July 2016. <http://www.msf.org/en/article/msf-international-activity-report-2015>.

- Cumming-bruce, Nick. “Doctors Without Borders Says It Won’t Take E.U. Money for Refugees.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 17 June 2016.<http://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/18/world/europe/doctors-without-borders-says-it-wont-take-eu-money-for-refugees.html>.

- Hamblin, James. “Why Doctors Without Borders Refused a Million Free Vaccines.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, 14 Oct. 2016. <http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/10/doctors-with-borders/503786/>.

- Rosenberg, Matthew. “Pentagon Details Chain of Errors in Strike on Afghan Hospital.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 29 Apr. 2016.<http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/30/world/asia/afghanistan-doctors-without-borders-hospital-strike.html>.

- Combi, C., G. Pozzani, and G. Pozzi. “Telemedicine for Developing Countries. A Survey and Some Design Issues.” Applied Clinical Informatics4 (2016): 1025-050.

- Glenn, Ian C., Nicholas E. Bruns, Danial Hayek, Tyler Hughes, and Todd A. Ponsky. “Rural Surgeons Would Embrace Surgical Telementoring for Help with Difficult Cases and Acquisition of New Skills.” Surgical Endoscopy Surg Endosc(2016)

- Zachariah, R., B. Bienvenue, L. Ayada, M. Manzi, A. Maalim, E. Engy, J. P. Jemmy, A. Ibrahim Said, A. Hassan, F. Abdulrahaman, O. Abdulrahman, J. Bseiso, H. Amin, D. Michalski, J. Oberreit, B. Draguez, C. Stokes, T. Reid, and A. D. Harries. “Practicing Medicine without Borders: Tele-consultations and Tele-mentoring for Improving Paediatric Care in a Conflict Setting in Somalia?” Tropical Medicine & International Health (2012)

- S, Delaigue, Bonnardot L, Olson D, and Morand J.J. “Télédermatologie Dans Les Pays à Revenu Faible Et Intermédiaire : Tour D’horizon.” Medecine Et Sante Tropicales (2015): 365-72.

- Giambrone, Danielle, Babar K. Rao, Amin Esfahani, and Shaan Rao. “Obstacles Hindering the Mainstream Practice of Teledermatopathology.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2014): 772-80.

- “Store-and-forward Teledermatology Consultations for Primary Care Providers: A Pilot at Henry Ford Health System.” Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2014)

Sharif, thanks for the great post on what MSF is doing in bringing medical care to the least developed countries in the world. I was especially struck by the reason MSF cited for rejecting vaccines offered by Pfizer.

We saw the great potential of telemedicine in the Narayana Heart Hospital case and I do believe it has the potential to democratise access to health care. It’s interesting to note that telemedicine has been available for decades and has been so slow to spread. Why do you think that is?

Telemedicine was available in Somalia back in 1992, albeit only to the US military. (1) Back then a simple Kodak camera was linked to a 9.6Kbps satellite connection. The data transmission cost alone totalled $145 per session. You identify telecommunications infrastructure as a constraint, but surely connectivity even in East Africa has come a long way since 1992.

(1) CROWTHER, MAJ JB, and LTC RON POROPATICH. “Telemedicine in the US Army: case reports from Somalia and Croatia.” Telemedicine Journal 1.1 (1995): 73-80.

Thanks for the comment Sander! The question of why telemedicine is not more widespread is very interesting because you’re right, though it’s adoption has been increasing, it’s been rather slow. The context matters a lot. MSF is an interesting case study for telemedicine because it highlights two challenges to its growth: 1.) the need for centralization and coordination within a health system and 2.) the need for technological infrastructure for telehealth programs.

For MSF, the second challenges has been a greater issue for implementing telehealth. MSF has to prioritize providing basic healthcare needs to the areas it serves before it can tackle a telehealth program, and those basic needs are enormous obstacles in themselves.

For developed nations, the first challenge has been a greater issue. Telehealth in the US health system, for example, has been hindered by lack of infrastructure for reimbursement, liability and accountability protections and privacy. Conversely, unlike these more complex, developed health systems, MSF’s structure and ability to use its resources as it wishes lowers its barriers to entry for telehealth. MSF does not need to be a nation’s health system. Its model is structured on figuring out at which projects it can have the greatest, most needing impact and tackle the pockets of the world without healthcare.

If you’d like to see more ways of how MSF has been tackling telemedicine projects, feel free to check some programs here: http://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/article/msf-telemedicine-brings-care-patients-remote-areas

Thanks Sharif, for a thought-provoking post. I used to work with MSF in Swaziland, where they have taken over one of the four regions in the country that has been most affected by HIV/TB. I was helping them cost their community-based multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) pilot program to assess the feasibility of national scale-up. While Swaziland is not a conflict-ridden country and has much better infrastructure than Central, West, and East Africa, the areas in most need of help are those that are hardest to get to (we could only visit 2-3 patients per day in an 8-hour work day, since we would be going at 10 mph on post-rainy season, terribly muddy and mountainous road) and are the worst-off in terms of access to any reliable forms of infrastructure. While MSF certainly has invested in the local health system, without more fundamental, system-strengthening investments (e.g. developing a reliable electricity grid), their potential for impact is incredibly limited, as are their funds to do so in a world where there’s an unhealthy obsession with minimizing NGO overhead (as someone who used to help Ministries of Health create their budgets for their Ministries of Finance and submit applications to various donor agencies, this kind of tech investment would unfortunately be classified as ‘overhead’). Additionally, as an NGO that won’t be (and shouldn’t be) around forever, MSF shouldn’t be conducting this work single-handedly — it should work closely with the government to build up their health system so that an initiative like telemedicine is ‘building capacity’ rather than ‘adding capacity.’

Thanks for this perspective, that’s really interesting! I can’t imagine the true day-to-day challenges that arise in that work and how complicated it is to entertain solutions to them. You already highlight a handful of immediate, enormous obstacles right there like working with local governments, tackling perceptions of overhead, developing an electricity grid, and just transportation through unforgiving terrain. It’s awesome you worked on this in Swaziland. Finding personnel for these projects is a challenge itself. The BMJ estimated a $2.17 billion in lost investment from emigration of doctors from sub-Saharan Africa (http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d7031). The MSF might be able to make a small dent in that.

Awesome post, Sharif!

I see a great deal of promise in the domain of tele-medicine, but how would physicians deal with liability? What happens if a diagnosis or treatment is done incorrectly, and the “blame” cannot be attributed to a particular, identifiable individual? Perhaps this issue is less relevant in a development context given the more “dire” circumstances (which I feel terrible saying, but hope you get my point)?

In a developed market context I think of Teladoc, which connects patients to doctors for one-on-one consultations for “general health” concerns, such as cases of fever, asthma, cold, pink eye, and eye infection.[1] However, the MSF telemedicine process appears to involve relatively more serious / invasive procedures where the downside risk of misdiagnosis could be higher. How far off are we from being able to distribute the workload of a procedure to a network of professionals in the United States?

[1] https://www.teladoc.com/what-can-i-use-it-for/

Ravi has a great post on Teledoc I encourage you check out! A system like teledoc’s implemented seamlessly in our health care system would be very cool.

I totally agree, liability in developed nations is definitely a big issue. It’s led to telemedicine being used more as a physician to physician consultation service where physicians can speak the same language to each other, minimize miscommunication, and trust that they’d give each other reliable information without important omissions. Patient- physician telemedicine interactions are more risky and consequently have a higher burden of proof in showing safety, efficacy and reliability. For each telehealth application, there have been a handful of studies looking at the error-rates of each of these systems.

Thanks for this post Sharif. I never knew surgery could be performed remotely!

Agree that MSF is a perfect application of telemedicine = where the alternative is no care at all. This also completely transforms the model of one looking to volunteer with MSF; instead of travelling to the country, volunteers can provide services remotely, which greatly increases efficiency.

I also wrote my post on telemedicine, and I’m curious as to your perspective on this: for what types of ailments does LI work best?